Archive

Fiscal rules: a return to the past that condemns Europe to irrelevance.

[As usual lately, this is an English AI translation of a piece written in Italian, updated to take into account yesterday’s European Parliament vote]

After three years of near-inaction, and a few months of frantic negotiations, European finance ministers have finally reached an agreement on the reform of the Stability and Growth Pact., that is now being discussed with the European Parliament. At first glance one might think, looking at the ballet of percentages, safeguard clauses, classifications, that this is a technical issue, for insiders. Nothing could be further from the truth. What was at stake, in the discussion that ended with the December last-minute agreement, was the framework within which European countries will have to operate in the coming years to face the challenges that await them. Few things are more relevant today. And that’s why it was a bad agreement. A return to the past that condemns the already battered Europe to irrelevance.

The old Pact now relegated to the attic faced widespread criticism: for its baroque complexity and reliance on numerous, at times arbitrary indicators; for its emphasis on one-size-fits-all yearly limits, fostering short-term discipline that, in effect often turned pro cyclical; for its bias against public investment. Most importantly, the old Pact was consistent with a worldview where the state’s role in the economy had to be limited among other things by imposing restrictive rules on fiscal policies.

That world no longer exists, and this explains the opening, in 2020, of the reform process of the Stability Pact. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the calamitous management of the euro crisis, the pandemic and finally inflation, have shown that there can be no stability and growth without stabilisation policies, without adequate levels of public goods such as health and education, without industrial policies and public investment for the ecological and digital transitions. In short, without an active role of the state in the economy.

For this reason, the discussion among academics and policy makers (largely ignored by governments, which woke up at the last minute) centered around the necessity for a philosophical shift. The new rule, it was widely believed, had to change this and put the protection of fiscal space for public policies a the centre of the stage (ensuring, of course sustainability of public finances). A change in philosophy that was to be found in the reform proposal put forward in 2022 by the European Commission. Albeit imperfect, the proposal abandoned the one-size-fits-all annual targets in favor of medium-term plans designed by countries in agreement with the Commission, in a framework that would guarantee debt sustainability and try to achieve an (excessively) moderate protection of public investment.

That framework is still there, but it has been transformed in an empty shell. On paper, multi-annual plans and investment protection still exist. But Germany, reverting to its old obsession with austerity, has imposed a plethora of complex (and as baroque as those of the old Pact) safeguard clauses that will be triggered in the event of excessive debt or deficits (i.e., almost always for almost everyone) and which, overruling the plans agreed with the Commission, go back to imposing one-size-fits-all annual numerical constraints, sometimes even more restrictive than the old rule. Like in the widely criticized old Stability Pact, debt reduction is still the alpha and omega, and it is no coincidence that all frugal countries rejoice that the new rule will be more effective in forcing fiscal discipline than the old one.

The Italian and French governments, the only ones that could have turned the board over, settled for a bare minimum, some short-term flexibility, in order to arrive at their respective elections with some money to spend. A short-sighted and depressing strategy: the elections, and these governments, will pass, but the rule will remain and tie our hands, while China and the United States make colossal investments in the future. It’s all right, as long that those celebrating victory today do not to come and tear their clothes in a few years’ time, when Europe will have become even more irrelevant than it is today.

Wolfgang Schäuble’s Ideas are Alive and Kicking

[As usual lately, this is an English AI translation of a piece written for the Italian Daily Domani]

Wolfgang Schäuble was a central figure in the German political landscape. A member of parliament for the centre-right Christian Democrats party from 1972 until his death on Tuesday evening at the age of 81, he was very close to Chancellor Helmut Kohl and, as a lawyer, one of the negotiators of the treaty that brought about the reunification with East Germany. But it was with Angela Merkel as Chancellor that Schäuble became known beyond national borders. For a few years Minister of the Interior, he was appointed Minister of Finance in 2009, a few weeks before the revelations about the state of Greek public finances that triggered the sovereign debt crisis. Since then, he has been one of the central figures in the calamitous management of the crisis. A staunch pro-European, he has nevertheless always been convinced, in homage to the ordoliberal doctrine, that integration could only be achieved by harnessing the European economy in a dense network of rules that would guarantee the public and private thrift necessary to make the EU competitive on world markets. Schäuble was the main standard-bearer of the “Berlin View” (or Brussels or Frankfurt, being adopted by the heads of the European Commission and the ECB of the time) which attributed the debt crisis to the fiscal profligacy and lack of reforms of the so-called “peripheral” EMU countries. A narrative about the crisis that forced “homework” (austerity and structural reforms) on the countries in crisis: we owe to Schäuble’s intransigence, backed by Angela Merkel, the Commission and the ECB (and sometimes against the IMF, which often had a more pragmatic approach), the draconian conditions imposed on Greek governments in exchange for financial assistance from the so-called Troika. In those years, he and the then president of the ECB, Jean-Claude Trichet, argued, against all empirical evidence, for expansionary austerity, the idea that fiscal restriction would supposedly free markets’ animal spirits and thus revive growth. An austerity that Schäuble imposed on countries in crisis but also followed at home. On the occasion of his departure from the Ministry of Finance in 2017, the photo of the employees forming a large zero in the courtyard in homage to the achievement of a balanced budget objective went around the world.

History has taken it upon itself to show the ineffectiveness and cost of that strategy. Not surprisingly, austerity is almost never expansionary and certainly has not been so in the eurozone. The fiscal adjustment imposed on the EMU peripheral countries triggered a crisis which for some of them had not yet been absorbed by the end of the decade. A crisis that, moreover, could have been less painful if the countries in better shape had supported the eurozone growth with expansionary policies, instead of adopting a restrictive stance themselves. The EMU is the only large advanced economy that suffered a second recession in 2012-13, after the Global Financial crisis of 2008. Not only that: since then, domestic demand has remained anaemic, and the European economy has become “Germanized”, managing to grow only thanks to exports; this contributes to the growing trade tensions, and Germany stands accused by international bodies and by the United States of exerting deflationary pressure on the world economy.

The narrative of a crisis caused by the fiscal irresponsibility of spendthrift governments quickly lost its luster and already in 2014 many of its initial supporters (e.g. Mario Draghi, who in the meantime became president of the ECB) opted for a more “symmetrical” explanation, according to which the trigger of the crisis were balance of payments imbalances of which the over-spendthrift and the over-austere countries were equally guilty. But Schäuble never backed from his belief that the only necessary medicine was the downsizing of public spending; Germany also imposed this view to its partner when reforming the European institutions (from the ESM to the fiscal compact).

With the Covid crisis and Germany’s staunch support for Next Generation EU, it seemed that the ordoliberal doctrine finally went into retirement, along with Schäuble, its proudest partisan. But recent events show us that this was wishful thinking. Schäuble would probably have approved the (non-)reform of the Stability Pact imposed by his successor Lindner, whose only guiding light is the reduction of public debt. Schäuble has left us, but the fetish of public and private thrift as a healing virtue is alive and well.

On the Stability Pact, no hurry. For once, let’s try to be forward looking.

[Note: this is a slightly edited ChatGPT translation of an article for the Italian daily Domani]

This Fall the right-wing Italian government will face a difficult balancing act, with a resource-less budget law and slowing growth. It is then not a surprise that in recent weeks members of the cabinet finally woke up, rediscovering the debate about the reform of European rules. Ministers Giorgetti (Treasury) and Fitto (European Affairs) sounded the alarm about the possible return of the Stability Pact, suspended since 2020.

It is useful to summarize the situation, for those who did not follow the discussion in the past months. With the pandemic, in March 2020, the European Commission immediately activated the Stability and Growth Pact suspension clause to allow European countries to respond to the health and economic crisis with budget policies. The Pact was actually already under heavy criticism, so much so that the Commission had already launched a consultation process on its revision. Some, including myself, had criticized the Pact even during the “great” (and illusory) convergence in the early 2000s. But the flaws became evident with the sovereign debt crisis when the European rules, instead of securing the economy and public finances, had the opposite effect: austerity sunk the economies of so-called peripheral countries (primarily Greece, but also Italy, Portugal, and to a lesser extent Spain) without making their public finances more sustainable. Many economists (including those from the Commission) now agree that in addition to forcing countries to implement pro-cyclical policies (budget restriction in an economic crisis), the existing rules hinder public investment, industrial policies, and inequality reduction. Above all, they turn budget laws into exercises in trimming decimal percentage points of deficits, rather than moments for planning public policies to address the major challenges we face.

The Commission, which had strongly supported austerity policies in the 2010s, deserves praise for the change in perspective that emerged from a working proposal put forward at the end of 2022. Without going into details, that proposal, despite its flaws, abandoned the idea that the sole guiding principle of public policies should be debt reduction and envisioned a rule that would allow each country ample leeway to autonomously design its budget policies over multi-year horizons, as long as the sustainability of public finances was guaranteed.

Unfortunately, despite being silent for a while following the disasters of the 2010s and being forced by the pandemic to accept a more active role for budget policies, the hawks of public finances, the so-called “frugals,” have reemerged at the earliest opportunity. Thus, the German Finance Ministry published a short text last spring that called the Commission to order just a few weeks before it presented a formal legislative proposal. In fact, that proposal, compared to the November 2022 document, marked a return to the guiding principle of debt reduction and annual deficit targets. All this happened in the substantial silence of the Italian, French, and Spanish governments. I cannot recall a single intervention by the leaders of these countries in support of the Commission under attack from frugal countries.

Today something is changing. The idea of a “golden rule” is back, allowing certain investments (ecological transition, digitalization, and defense, to obtain approval from Eastern countries) to be excluded from the deficit calculation. Italy, France, and Spain are struggling to coordinate on this rule in anticipation of the finance ministers’ meeting in the coming weeks. Even the German government, given the growth crisis and the industrial and infrastructural obsolescence plaguing the country, might compromise, especially if it obtained a relaxation of the state aid regulations in return.

Perhaps the hawks have not yet won, and there is room for an improvement of the current fiscal framework. Now the main risk is that, fearing that the old Pact will come back into force on January 1, 2024, we settle for a compromise that lowers the bar. The world is changing quickly, and the risk of Europe becoming economically and geopolitically irrelevant has never been higher. Industrial policies and public investment will be the main leverage to ensure growth and positioning in future sectors. The Chinese and American governments understood this years ago, while we continue to formulate ambitious programs that we do not adequately finance, pulling in all directions a blanket that remains inexorably short.

We cannot be satisfied with some cosmetic adjustments to a framework that remains oriented towards reducing spending and public debt. Given the stakes, the January 1 deadline should be the least of our problems. The new rule will remain in effect for years, and it is better to adopt a good rule late than a bad one on time. It’s so obvious that it seems absurd to have to emphasize it. If a serious and in-depth negotiation could be initiated that goes beyond the fall, the Commission could extend the suspension clause or adopt all the flexibility necessary to prevent the old Pact from biting.

Of course, we have had three years, and it is depressing that on this topic, much more important than many others, we have waited until the last moment to act. The only visible participants in the European debate have been the Commission, which has done its job, and the frugals, led by Germany, who have occupied the field. The Italian and French governments were MIA, and today we are paying the price for this absence. Shortsightedness continues to be the common thread that ties the leadership of European countries.

Masochistic Germany is a problem for all of us.

[Note: this is a slightly edited ChatGPT translation of an article for the Italian daily Domani ]

Recently, the German Minister of Finance, the liberal Christian Lindner, announced his intention, while preparing the budget law for 2024, to return to “fiscal normality.” This means reverting to the fiscal rule suspended in 2020 (the Schuldenbremse or debt brake), which mandates reducing the debt to below 60% of GDP. With the exception of defense, all ministries are supposed to face reduced allocations. Particularly noteworthy is the fact that the Ministry of Family Affairs, led by the Green Party’s Lisa Paus, will likely not be able to finance the child poverty reduction program which was a central focus of the government’s social protection agenda.

Lindner, a hawk who has been pressing for a swift return to budget discipline since the coalition government with the Greens and Social Democrats took office, likely has a dual objective. Internally, he aims to demonstrate his ability to steer the policies of the contentious and indecisive traffic light coalition. Externally, he seeks to influence the European debate on the rule that will replace the Stability Pact, showcasing his country as an example of fiscal probity.

Germany is pushing for the new European fiscal rule to be only a slightly revised version of the current one (suspended until the end of 2023), prescribing a swift return to public debt at 60% of GDP. The urgency for a large part of the German political class to close the chapter of Covid and return to an economy governed by frugality is striking.

This haste is puzzling for two reasons. Firstly, the German economy is facing a conjunctural crisis, with two consecutive quarters of (slightly) negative growth formally putting it in recession. Regardless of this, Germany has not yet recovered the activity levels of 2019 and ranks at the bottom among OECD countries in terms of growth since the pandemics. This under performance can be attributed to contingent factors, such as the impact of the War in Ukraine and the rising energy prices, which affected Germany more than others due to its geographical position and industrial specialization. However, there are also more structural factors, such as the struggling sectors where German firms are unable to keep up with technological innovation and competition from emerging countries. A notable example is the automotive industry, where German companies, leaders in combustion engines, lag behind in electric vehicles, in which China has gained a significant advantage. Under such circumstances, reducing public support to the economy through self-imposed austerity appears particularly self-harming.

Secondly, the myth of budget discipline so widely spread among German policy makers seems particularly incomprehensible because, even before the pandemic, the many years of past frugality, both public and private, were already taking their toll. Since the early 2000s, Germany has pursued a growth model driven by exports, based on domestic demand compression. Between 2000 and 2019, German business investment was significantly lower than the Eurozone average. Although the difference is less significant for public investment, it is only because public capital has grown at very low rates throughout the Eurozone. Germany had an average net public investment of zero between 1999 and 2015, while the Eurozone as a whole saw positive figures (albeit insufficient and declining during the sovereign debt crisis years). The Covid period, with its recovery in public and private investments, now seems to already be over. The result of this investment compression, especially in the public sector, is a capital deficiency that will constrain German growth in the coming years. The aging population will exacerbate this issue by reducing the labor force. Many studies associate the future aging population with further reductions in investment, labor productivity, and consequently, potential growth.

Even before the pandemic, there was a consensus among German economists that to address the infrastructural deficit accumulated since the early 2000s, Germany needed to engage in a massive investment program of around 40-50 billion euros annually for a decade. But in reality, the needs are much higher. After the pandemic, it became clear to everyone that the focus should not be limited (not just in Germany) to physical infrastructure alone. Social capital (education and healthcare, for example), which suffered greatly during the years of austerity, is equally important to ensure balanced growth. In 2018, a report coordinated by Romano Prodi estimated the EU’s annual social investment deficit at 100 billion euros. Last, but not least, the massive investment needs related to ecological transition and decarbonization of the economy will further increase the total amount.

In short, when considering the need to renew a crumbling infrastructure, the ambitious and indispensable climate objectives of the EU, the social capital deficiency (especially in healthcare, one of the ministries hit hardest by Lindner’s announced cuts), the additional investments needs become colossal. A group of economists I collaborate with for the European Public Investment Outlook series estimates these needs to be between 600 and 800 billion euros over the next decade, which is equivalent to 1.6% to 2.1% of GDP each year. It is evident that these figures are in no way compatible with the “debt brake” and the announced contraction of public spending. Ironically, during his inauguration speech, Chancellor Scholz spoke of the “government of investment”…

Things become even more complicated, making Lindner’s announcements even more baffling, when considering the timeline of investment needs. As my German colleagues argue, infrastructure investments can be spread over an extended period, allowing for modulation based on the need for counterciclicality (more investments during slowdowns and fewer during booms) and avoiding bottlenecks. However, decarbonizing the economy requires, due to the delays accumulated in previous years, that investments be made as soon as possible. These are mainly private investments (in transportation and thermal conversion of the building stock); but, as the German colleagues point out, for this massive effort to succeed, it must be accompanied and partly financed by the government through subsidies and tax incentives.

In conclusion, faced with a changing world, Germany seems to be turning backward, heedless of the fact that the old ordoliberal doctrine has proven to be woefully inadequate in preparing the country for future challenges. One might be tempted to comment that it’s their problem, not ours. However, that would be utterly mistaken. In the coming months, the debate on the reform of the Stability Pact will intensify. A German leadership stubbornly clinging to the past will be a problem for all of us.

Germany’s longing for the Ancien Régime is a Threat for Europe

Note: this is a rough translation of a piece published on the Italian neswpaper Domani, with a few edits and additions.

While the campaign for the election captures all the attention of the Italian establishment, we should not stop looking beyond our borders. In particular, the lack of interest in what is happening in Germany is striking and worrisome. The difficulties Europe’s largest economy is experiencing will in fact have far more significant consequences for many European countries than their domestic political struggles.

Last week, the ministry of economy and ecological transition (headed by the vice-chancellor and number two of the Green party, Robert Habeck) published a report on the reform of the stability pact, which, although we tend to forget it, will be THE topic of the coming months. The guiding principles for reform that the report outlines are basically a re-proposal of the existing rule, as if the disasters of the sovereign debt crisis and the Covid tsunami were a parenthesis to be closed as soon as possible by returning to the old world.

Under a gleaming hood, the German engine has been in crisis for years

There will be time to return to the inadequacy of this proposal (Carlo Clericetti does it well in the Italian magazine Micromega) and to the issue of European governance. What I would like to emphasise here is that the German elites, with this frenzy to return to the past, do not seem to fully grasp at least two things: First, the fact that after the experience of the last ten years it is not possible to return to an idea of economic policy for which the only beacon is fiscal discipline, neglecting public investment, industrial policy, social protection and so on. Second, and this is more surprising, they do not grasp the fact that the German growth model seems to have hit its boundaries. As a reminder, we are talking about a model aiming at export-led growth, that was based on the one hand on the compression of domestic demand (with wages that for decades grew much less than productivity); on the other hand it was based on an export sector that took advantage of both the dualism of the labour market and of value chains rooted in the countries of the former Soviet bloc. Germany could therefore import intermediate goods and low-cost components and re-export finished products, often with a high technological content, to non-European markets. This is the main reason why it remained a manufacturing power while most advanced countries had to cope with de-industrialisation and relocation.

Many, including myself have criticised this model, which during the sovereign debt crisis Germany successfully managed to generalise to the rest of the eurozone. In 2020, in concluding an essay on Europe, I pointed out how that model has come to an end. The public and private investment deficit, the result of decades of self-imposed frugality, has progressively depleted the capital stock and reduced the competitiveness of German industry. Meanwhile, while the growth of emerging countries has helped to provide outlets for German goods, it has also seen these countries develop high value-added production that competes with German exporting firms. But there is more: I also noted that the progressive distortion of the ordoliberal model, the increase in inequality and precariousness (which contributes to demographic stagnation and to the ageing of population), and the growing dependence on foreign demand, more problematic than ever in an increasingly uncertain geopolitical context, have all contributed to making Germany a giant with feet of clay.

A Giant with Feet of Clay

Feet of clay that today are cracking. The bottlenecks that appeared during and after the pandemic, due to lockdowns and to the recomposition of global supply and demand, have (not surprisingly) proved to be more persistent than many expected. Furthermore, the acceleration of investment in the ecological transition, obviously welcome and all too late, creates shortages particularly in sectors that are key for the German economy, such as the automotive. Finally, geopolitical tensions, the slowdown in emerging economies, and of course the war in Ukraine greatly reduce the outlets for the German export sector and have laid bare the short-sightedness of the past German leadership’s choice to rely on Russian oil and gas, admittedly reducing costs, but creating a dependency for which the country is now paying the price. It is important, however, to emphasise again that the events of the last two years have only come to add to the structural problems of a model of growth and organisation of production that was beginning to show its limits even before the pandemic.

The German elites at a crossroads

In 2020, I concluded my essay by stating that the crisis of the German model could have been an opportunity for Europe, as it would have forced Germany to worry about the imbalances within the eurozone, to promote public and private investment, to rethink industrial policy, to support (German and European) domestic demand; not out of altruism, but to create a stable European market in an international context that had become structurally uncertain and turbulent. The heartfelt support for Next Generation EU seemed to confirm the feeling that something had changed in Germany. The recent turn of the German debate is therefore worrisome and should be looked at closely. Habeck’s paper and the recent stances of the Minister of Finances, the liberal Lindner, point to a kind of “ostrich syndrome” of the German elites, who seem to long for a return to the past in order not to have to deal with the structural problems of Germany and of European integration. If this tendency prevails, not only the German citizens but the whole of Europe, which will slip into irrelevance, will pay the price in the coming years. On the contrary, representatives of the German government at European tables need to be called upon to contribute to the rethinking of industrial and energy policy and public investment policies, to the development of a European welfare state, to the definition of budget rules that allow for active and sustainable policies, to the development of the internal market, to the completion of the banking union, and the list could go on. In short, an ambitious and wide-ranging European discussion is needed to make the German elites look away from their navels and try to restore Europe’s centrality at a time of great geopolitical turbulence (which will certainly extend well beyond the war in Ukraine). France and Italy, because of their size and the influence they have had in Europe in the recent past, would obviously play a key role in countering the return to the past of the German elites. This is why the absence of European issues from the (pre-electoral) Italian and (post-electoral) French debate cannot but cause concern.

Public Debt. I can’t Believe we are Still There

The crisis is supposedly over, as the European economy started growing again. There will be time to assess whether we are really out of the wood, or whether there is still some slack. But this matters little to those who, as soon as things got slightly better, turned to their old obsession: DEBT! Bear in mind, not private debt, that seems to have disappeared from the radars. No, what seems to keep policy makers and pundits awake at night is ugly public debt, the source of all troubles (past, present and future).

Take my country, Italy. A few days ago this tweet showing the difference between the Italian and the German debt made a few headlines:

La differenza tra #debitopubblico italiano e quello tedesco è la più elevata dall’introduzione dell’ #euro e continua a crescere. Il dibattito è aperto… pic.twitter.com/mDMkHl9ipi

— Carlo Cottarelli (@CottarelliCPI) January 22, 2018

The ratio increased, so DEBT is the Italian most pressing problem. Not the slack in the labour market. Not the differentials in productivity. I can’t stop asking: why aren’t Italians desperately tweeting this figure?

This shows the relative performance of Italy and Germany along two very common measures of productivity, Multifactor productivity and GDP per capita. I took these variables (quick and dirt from the OECD site), but any other measure of real performance would have depicted a similar picture.

So what? The public debt crusaders will argue that precisely because of debt, Italy has poor real performance. The profligate public sector prevented virtuous market adjustments, and hampered real convergence. The causality goes from high debt to poor real performance, they will argue. Reduce debt!

Well, think again. Research is much more nuanced on this. A paper by Pescatori and coauthors shows for example that countries with high public debt exhibit high GDP volatility, but not necessarily lower growth rates. High but stable levels of debt are less harmful than low but increasing ones. In a recent Fiscal Monitor the IMF has shifted the focus back to private debt (which, it is worth remembering is the root cause of the crisis), arguing that the deleveraging that will necessarily continue in the next few years will require accompanying measures from the public sector: on one side, renewed attention to the financial sector, to make sure that liquidity problems of firms, but also of financial institutions) do not degenerate into solvency problems. On the other side, the macroeconomic consequences of deleveraging, most notably the increase of savings and the reduction of private expenditure, may need to be compensated by Keynesian support to aggregate demand, thus implying that public debt may temporarily increase in order to sustain growth (self promotion: the preceding paragraph is taken from my book on the relevance of the history of thought to understand current controversies. French version available, Italian version coming out in March, English version coming out eventually).

In just a sentence, the causal link between high debt and low growth is far from being uncontroversial.

Last, but not least, it is worth remembering that Italy was not profligate during the crisis; unfortunately, I would add. Let’s look at structural deficit (since 2010; ask the Commission why we don’t have the data for earlier years), which as we know washes away the impact of cyclical factors on public finances.

The Italian figures were slightly worse than the German ones, but not dramatically so. And if we take interest expenditure away, so that we have a measure of what the Italian government could actually control, then Italy was more rigorous (Debt obsessive pundits would use the term “virtuous”) than Germany.

The thing is that the Italian debt ratio is more or less stable, in spite of sluggish growth (current and potential) and low inflation. It is not an issue that should worry our policy makers, who should instead really try to boost productivity and growth. Said it differently, it is more urgent for Italy to work on increasing the denominator of the ratio between debt and GDP than to focus on the numerator. And I think this may actually require more public expenditure and a temporary increase in debt (some help from the rest of the EMU, starting from Germany, would not hurt). It is a pity that the “Italian debt problem” is all over the place.

A German Model?

Tomorrow Germany votes, and there is little suspense, besides the highly symbolic question of whether the far right will make it into the Bundestag.

Angela Merkel will be Chancellor for the fourth time, marking a long period of political and policy stability. In the past fifteen years Germany emerged as the model to follow for the other large economies. For since its economy has performed better, in terms of growth and unemployment, than France or Italy.

I have at discussed at length, here and elsewhere, the costs of the German success in terms of global imbalances and uncooperative behaviours. Last week I wrote a piece for the newly born magazine LuissOpen (Ad: Follow it on twitter! There is plenty of interesting content well beyond economics! End of Ad).

The piece lists, in a non exhaustive way, a number of weaknesses that can be spotted behind the shining macroeconomic results, and also argues that there is much more than labour market liberalization behind a successful economic model (including in Germany).

The original piece can be found here (and here in Italian). I copy and paste it below

Three months after his commencement, Emmanuel Macron delivered last week one of the most important, and controversial, promises of his agenda. The loi travail that will become operational in the next few weeks mostly deals employment protection, which is weakened especially for small and medium enterprises. The aim is to lift constraints for firms hiring, and thus increase employment. This first set of norms should be followed in the next weeks or months by norms aimed at improving training and employability of unemployed workers. Once completed, the package would be the French version of the flexicurity that Scandinavian countries put in place in the past, with different degrees of success.

Without entering into the details of the law, the set of norms approved by the French government, just as the Italian Jobs Act voted in 2014, is a bold step towards the flexibilization of labour market relations that Germany has in place since the early years 2000, with the so-called “Hartz Reforms”. The German experience, and to a minor extent the first few years of application of the Job Act, can help understand how the French labour market could evolve in the next few years.

Germany in fact sets itself as an example. The argument goes that the reforms it implemented in 2003-2005, did liberalize labour markets, and since then, with the exception of the first years of the crisis, unemployment has been steadily decreasing. But in fact, this is a misleading example, because the Hartz reforms were embedded in a complex institutional setting, which goes well beyond labour market flexibility.

First, an important segment of the German labour market, the one linked to manufacturing and business services, has always been ruled by long-term agreements between employers, workers, and local work councils. For these insider workers a system of work relations was in place, in which highly paid workers acquired skills through vocational training (within or outside the firm), and were protected by an all-encompassing welfare system. Vocational training created robust bonds between the firms, that had often invested substantial resources in the training, and the workers, whose specific skills could not easily be transferred to other sectors or even to other firms.

At the turn of the century, globalized markets coupled with the aftermath of the reunification, exerted a serious pressure for a restructuring of labour relations. This restructuring happened through a consensus process that did not involve the government, and kept untouched the bond between the firm and the worker created by vocational training.

The mutual interest in preserving the long-term relationship between workers and firms in the insider markets, led to agreements aimed at reducing costs or to increase productivity without increasing turnover or reducing average job tenure. These agreements could involve on the workers’ side labour sharing, flexibility in hours and in labour mobility, wage concessions, reductions in absenteeism. In exchange for this, firms would guarantee continued investments in innovation and in the (vocational) training of workers, and job security.

It is crucial to understand that the Hartz reform did not touch the insiders market (manufacturing, finance, insurance and business, etc), that as we just said had already begun restructuring without government intervention. The reform made the welfare system less generous, while allowing access to benefits even for workers with low earnings, thus de facto introducing incentives to low-paid jobs. Furthermore, it liberalized temporary work contracts, and made more flexible a few sectors subject to competition from posted workers (i.e. construction).

The combined result of reforms and endogenous restructuring yielded a spike in part time jobs, and an increase of employment. But it also widened the gap in earnings and in protection between workers in the export-oriented sectors and the others.

The second feature of the German system that made it resilient during the crisis is the existence of a dense network of local public savings banks (the Sparkassen). Savings bank were a defining feature of the banking sectors of a number of European countries (e.g. Spain, Italy), but have progressively become marginal. Germany is therefore an exception in that its local savings banks are still a pillar of its economy.

Local savings banks have specific public interest missions, as they are involved in the development of local communities, and in financing households and firms (in particular SMEs). The law only allows operation within the region of competence, which shields them from competition while keeping them close to their stakeholders. Similarly, the ambit of their operations is limited (for example, they face limits in their capacity to engage in securities trading or in excessively risky financing).

To avoid that these limitations hamper their effectiveness and their solidity, the banks work as a network among them. The network exhibits economies of scale and of scope, while remaining close, in its individual components, to local communities. Furthermore, the existence of solidarity mechanisms (rescue funds) ensures that temporary difficulties of a bank are tackled without spreading contagion.

The major private commercial banks, very active in international markets, did suffer like in most other countries, were a drain on public finances, and drastically contracted their lending to the real sector. The Sparkassen on the other hand kept their financing steady (especially to SMEs) and required virtually no state aid. As a consequence, the local savings banks cushioned the impact of the financial crisis on the German economy, and their continued financing of firms is certainly a major factor in explaining the quick rebound of the German economy after 2010.

If taken together, the banking sector and the labour market institutions design a remarkably efficient system, geared towards the establishment of long run relationships in which the interests and the objectives (between entrepreneurs and workers, between banks and firms) were aligned.

But this effectiveness did not come without costs. From a macroeconomic point of view, profitability and competitiveness increased, but also precautionary savings, induced by a less generous welfare state, and by the increased uncertainty faced by workers. The “success” of the German export-led economy, that had a 9% current account surplus in 2016, is based on the compression of domestic demand, and on a labour market that is increasingly split in two, and in which inequality increased dramatically. The low unemployment that should make other countries envious hides a massive increase of the so-called working poor. (See figure 2 here)

I would push this even further: the Hartz Reform had a strong impact on labour market dualism and precariousness, but only a minor one in explaining the resilience of the economy. A recent CER policy brief makes a somewhat similar point.

Following the Jobs Act, the Italian labour market seems to be headed in a similar direction as the German one. The recent data released by ISTAT on labour market development certified the return of employed people to the pre-crisis peak (2008), thus marking, symbolically the end of the crisis. Yet, GDP is still 7% below its 2008 level, meaning that the increase of employment happened in low value added sectors (such as for example tourism and catering), and often with part-time contracts. These are typically sectors with low and very low wages, and stagnant productivity dynamics. At the same time, wages (but not employment) increase in manufacturing-export oriented sectors. The Italian labour market, in a sentence, is heading towards the same dualistic structure that characterizes the German one. This explains why, like in Germany, Italian domestic demand stagnates; why the increase in employment is obtained at the price of increased precariousness and of the working poor; why, finally, while the numbers say that the crisis is beyond us, the actual experience of households is often different. Italy, and to a minor extent Germany, are the best proof that employment and growth do not necessarily go hand in hand with increased well-being.

Focusing exclusively on labour market flexibility, Italy and in France only imported one element of the German “model”; and probably the one that is by far the least important. The German capacity to put in place long term relationships, the real key to economic resilience success, is lost in our countries.

The End of German Hegemony. Really?

I was puzzled by Daniel Gros’ recent Project Syndicate piece, in which he claims that Germany’s dominance of the EMU may be coming to an end. Gros’ argument is based on two facts. The first is the slowing growth rate of Germany, that seems to be heading towards the pre-crisis “normal” of slow growth (Germany grew less than EMU average for most of the period 1999-2007). The second, more geo-political, is the lack of willingness (or of capacity) to manage, the crises that face the EU (in particular the refugees crisis).

Gros concludes that this loss of influence is dangerous, because Germany will not be able to resist the changes in policies that are pushed by peripheral countries and by the ECB. Of course, implicit in this statement, is Gros’ belief that these policies were necessary and useful.

I welcome the recognition that Germany has steered the EMU since the beginning of the crisis. Those of us talking about the Germanification of Europe have been decried until very recently. Yet, I do not share, not at all, Gros view.

True, Germany’s growth is slowing down. These are the risks of an export-led growth model: countries are not masters of their own fate. Germany stayed clear from the peripheral countries’ crisis (that it contributed to create) by turning to the US and to emerging economies as markets for its exports. But now that these countries are also having problems, the limits of jumping on other countries’ shoulders to grow, become evident. I am surprised by Gros’ surprise, as this was evident from the very beginning.

But here I do not want to reiterate my criticisms of the export-led model, starting from the fallacy of composition. Instead, I would like to challenge Gros’ argument that Germany influence is waning. I would say on the contrary that the Germanification of the eurozone is almost complete.

I took a few macroeconomic variables, and contrasted Germany with the remaining 11 EMU members. Let’s start with (missing) domestic demand, a defining characteristic of the export-led growth model:

Since 2007, the yellow line (EMU11) and the red line (Germany) converged, mostly because domestic demand in the rest of the EMU was reduced. This led of course to an increased reliance of the EMU as a whole on exports. The EMU as a whole had an overall balanced external position in 2007, while it has a substantial current account surplus today (the EMU12 went from 0.5% to 3.4 projected for 2016. Germany went from 7% to 7.7%). In other words, the EMU11 joined Germany on the shoulders of the rest of the world.

Austerity has of course much to be blamed for this compression of domestic demand: Just look at government balances (net of interest payments):

True, the difference between Germany and the rest of EMU is today larger than in 2007. But since Germany and the Troika took the driving seat in 2010, government balances of the EMU11 have been steadily converging to surplus, and they are not going to stop in the foreseeable horizon (the Commission forecasts go until 2016).

Finally, if we look at one of the main drivers of growth, investment, the picture is the same.

Be it private or public, the EMU11 Gross Fixed Capital Formation has been converging towards the (excessively low) German level (I did not draw the differences, not to clutter the figure).

And of course, there are labour costs, for which convergence to Germany was brutal, even if the latter, rather than EMU peripheral countries, were the outlier. To summarize, during the crisis the difference between Germany and the rest of the EMU was substantially reduced, and will continue to be in the next years:

The difference was reduced for all variables, except for government deficit. Self-defeating austerity slowed down the convergence. But private expenditure, in particular investment, more than compensated.

So, if I were Gros, I would not worry too much. The Germanification of Europe is well on its way. If Germany does not go to the EMU11 (it definitely does not!), the EMU11 keeps going to Germany.

But as I am not Gros, I worry a lot.

Convergence, Where Art Thou?

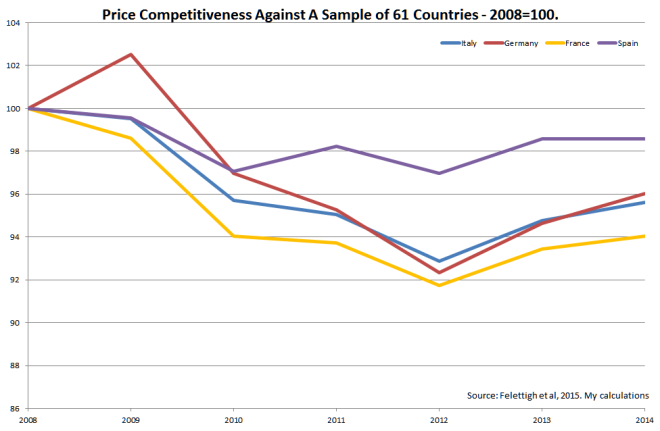

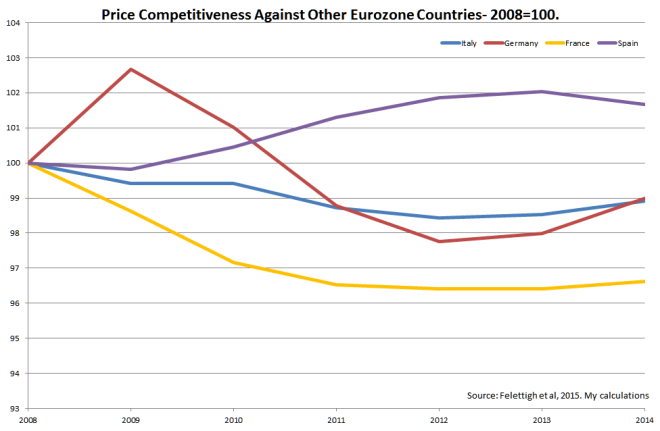

A new Occasional Paper details the new methodology adopted by the Bank of Italy for calculating an index of price competitiveness, and applies it to the four largest eurozone economies.

I took the time to copy the numbers of table 3 in an excel file (let’s hope for the best), and to look at what happened since 2009. Here is the evolution of price competitiveness (a decrease means improved competitiveness):

I find this intriguing. We have been sold the story of Spain as the success story for EMU austerity as, contrary to other countries, it restored its external balance through internal devaluation. Well, apparently not. Since 2008 its price competitiveness improved, but less so than in the three other major EMU countries.

The reason must be that the rebalancing was internal to the eurozone, so that the figure does not in fact go against austerity nor internal devaluation. For sure, within eurozone price competitiveness improved for Spain. Well, think again…

This is indeed puzzling, and goes against anedoctical evidence. We’ll have to wait for the new methodology to be scrutinized by other researchers before making too much of this. But as it stands, it tells a different story from what we read all over the places. Spain’s current account improvement can hardly be related to an improvement in its price competitiveness. Likewise, by looking at France’s evolution, it is hard to argue that its current account problems are determined by price dynamics.

Without wanting to draw too much from a couple of time series, I would say that reforms in crisis countries should focus on boosting non-price competitiveness, rather than on reducing costs (in particular labour costs). And the thing is, some of these reforms may actually need increased public spending, for example in infrastructures, or in enhancing public administration’s efficiency. To accompany these reforms there is more to macroeconomic policy than just reducing taxes and at the same time cutting expenditure.

Since 2010 it ha been taken for granted that reforms and austerity should go hand in hand. This is one of the reasons for the policy disaster we lived. We really need to better understand the relationship between supply side policies and macroeconomic management. I see little or no debate on this, and I find it worrisome.

Reform or Perish

Very busy period. Plus, it is kind of tiresome to comment daily ups and downs of the negotiation between Greece and the Troika Institutions.

But as yesterday we made another step towards Grexit, it struck me how close the two sides are on the most controversial issue, primary surplus. Greece conceded to the creditors’ demand of a 1% surplus in 2015, and there still is a difference on the target for 2016, of about 0.5% (around 900 millions). Just look at how often most countries, not just Greece, respected their targets in the past, and you’ll understand how this does not look like a difference impossible to bridge.

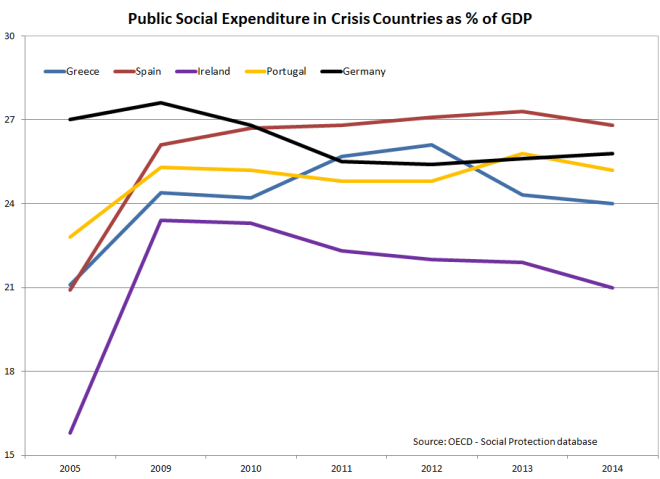

The remaining issue is reforms. Creditors argue that Greece cannot be trusted in its commitment to reform. After all, they cheated so often in the past… In particular, creditors point at one of Syriza’s red lines, the refusal to touch pension reforms, as proof that the country is structurally incapable of reform. And here is the proof, the percentage of GDP that crisis countries spent in welfare::

I took total social expenditure that bundles together pensions, expenditure for supporting families, labour market policies, and so on and so forth. All these expenditure that, according to the Berlin View, choke the animal spirits of the economy, and kill productivity.

Well, Greece does not do much worse than its fellow crisis economies, but it is true that it is hard to detect a downward trend. The reform effort was not very strong, and certaiinly not adapted to an economy undergoing such a terrible crisis. The very fact that after four years of adjustment program the country spends 24% of its GDP in social protection, is a proof that it cannot be trusted.This is just proof that, once more, the Greek made fun of their fellow Europeans, and that they want us to pay for their pensions.

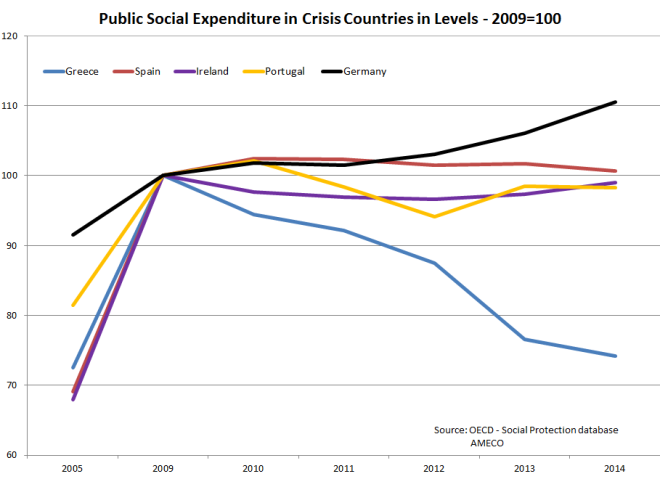

Hold on. Did I just say “terrible crisis”? What was that story of ratios, denominators and numerators? The ratio is today at the same level as 2009. But what about actual expenditure? There is a vary simple way to check for this. Multiply each of the lines above for the value of GDP. Here is what you get (normalized at 2009=100, as country sizes are too different):

The picture looks quite different, does it? Greece, whose crisis was significantly worse than for the other countries, slashed social expenditure by 25% in 5 years (I know, I know, it is current expenditure. I am too busy to deflate the figure. But I challenge you to prove that things would be substantially different). Now, just in case you had not noticed, social expenditure has an important role as an automatic stabilizer: It supports incomes, thus making hardship more bearable, and lying the foundations for the recovery. In a crisis the line should go up, not down. This picture is yet another illustration of the Greek tragedy, and of the stupidity of the policies that the Troika insists on imposing. By the way, notice how expenditure increased from 2005 to 2009, in response to the global financial crisis. A further proof that sensible policies were implemented in the early phase of the crisis, and that we went berserk only in the second phase.

Ah, and of course virtuous Germany, the model we should all follow, is the black line. Do what I say…

One may object that focusing on expenditure is misleading. There is more than expenditure in assessing the burden of the welfare state on the economy. While Greece slashed spending, its welfare state did not become any better; its capacity to collect taxes did not improve, that its inefficient public administration and its crony capitalism are stronger than ever. Yes, somebody may object all that. That someone is Yanis Varoufakis, who is demanding precisely this: stop asking that Greece slashes spending, and lift the financial constraint that prevents any meaningful medium term reform effort. Reform is not just cutting expenditure. Reform is reorganization of the administrative machine, elimination of wasteful programs, redesigning of incentives. All that is a billion times harder to do for a government that spends all its energies finding money to pay its debt.

Real reform is a medium term objective that needs time, and sometimes resources. In a sentence, reform should stop being associated with austerity.

But hey, I am no finance minister. Just sayin’…