Archive

A German Model?

Tomorrow Germany votes, and there is little suspense, besides the highly symbolic question of whether the far right will make it into the Bundestag.

Angela Merkel will be Chancellor for the fourth time, marking a long period of political and policy stability. In the past fifteen years Germany emerged as the model to follow for the other large economies. For since its economy has performed better, in terms of growth and unemployment, than France or Italy.

I have at discussed at length, here and elsewhere, the costs of the German success in terms of global imbalances and uncooperative behaviours. Last week I wrote a piece for the newly born magazine LuissOpen (Ad: Follow it on twitter! There is plenty of interesting content well beyond economics! End of Ad).

The piece lists, in a non exhaustive way, a number of weaknesses that can be spotted behind the shining macroeconomic results, and also argues that there is much more than labour market liberalization behind a successful economic model (including in Germany).

The original piece can be found here (and here in Italian). I copy and paste it below

Three months after his commencement, Emmanuel Macron delivered last week one of the most important, and controversial, promises of his agenda. The loi travail that will become operational in the next few weeks mostly deals employment protection, which is weakened especially for small and medium enterprises. The aim is to lift constraints for firms hiring, and thus increase employment. This first set of norms should be followed in the next weeks or months by norms aimed at improving training and employability of unemployed workers. Once completed, the package would be the French version of the flexicurity that Scandinavian countries put in place in the past, with different degrees of success.

Without entering into the details of the law, the set of norms approved by the French government, just as the Italian Jobs Act voted in 2014, is a bold step towards the flexibilization of labour market relations that Germany has in place since the early years 2000, with the so-called “Hartz Reforms”. The German experience, and to a minor extent the first few years of application of the Job Act, can help understand how the French labour market could evolve in the next few years.

Germany in fact sets itself as an example. The argument goes that the reforms it implemented in 2003-2005, did liberalize labour markets, and since then, with the exception of the first years of the crisis, unemployment has been steadily decreasing. But in fact, this is a misleading example, because the Hartz reforms were embedded in a complex institutional setting, which goes well beyond labour market flexibility.

First, an important segment of the German labour market, the one linked to manufacturing and business services, has always been ruled by long-term agreements between employers, workers, and local work councils. For these insider workers a system of work relations was in place, in which highly paid workers acquired skills through vocational training (within or outside the firm), and were protected by an all-encompassing welfare system. Vocational training created robust bonds between the firms, that had often invested substantial resources in the training, and the workers, whose specific skills could not easily be transferred to other sectors or even to other firms.

At the turn of the century, globalized markets coupled with the aftermath of the reunification, exerted a serious pressure for a restructuring of labour relations. This restructuring happened through a consensus process that did not involve the government, and kept untouched the bond between the firm and the worker created by vocational training.

The mutual interest in preserving the long-term relationship between workers and firms in the insider markets, led to agreements aimed at reducing costs or to increase productivity without increasing turnover or reducing average job tenure. These agreements could involve on the workers’ side labour sharing, flexibility in hours and in labour mobility, wage concessions, reductions in absenteeism. In exchange for this, firms would guarantee continued investments in innovation and in the (vocational) training of workers, and job security.

It is crucial to understand that the Hartz reform did not touch the insiders market (manufacturing, finance, insurance and business, etc), that as we just said had already begun restructuring without government intervention. The reform made the welfare system less generous, while allowing access to benefits even for workers with low earnings, thus de facto introducing incentives to low-paid jobs. Furthermore, it liberalized temporary work contracts, and made more flexible a few sectors subject to competition from posted workers (i.e. construction).

The combined result of reforms and endogenous restructuring yielded a spike in part time jobs, and an increase of employment. But it also widened the gap in earnings and in protection between workers in the export-oriented sectors and the others.

The second feature of the German system that made it resilient during the crisis is the existence of a dense network of local public savings banks (the Sparkassen). Savings bank were a defining feature of the banking sectors of a number of European countries (e.g. Spain, Italy), but have progressively become marginal. Germany is therefore an exception in that its local savings banks are still a pillar of its economy.

Local savings banks have specific public interest missions, as they are involved in the development of local communities, and in financing households and firms (in particular SMEs). The law only allows operation within the region of competence, which shields them from competition while keeping them close to their stakeholders. Similarly, the ambit of their operations is limited (for example, they face limits in their capacity to engage in securities trading or in excessively risky financing).

To avoid that these limitations hamper their effectiveness and their solidity, the banks work as a network among them. The network exhibits economies of scale and of scope, while remaining close, in its individual components, to local communities. Furthermore, the existence of solidarity mechanisms (rescue funds) ensures that temporary difficulties of a bank are tackled without spreading contagion.

The major private commercial banks, very active in international markets, did suffer like in most other countries, were a drain on public finances, and drastically contracted their lending to the real sector. The Sparkassen on the other hand kept their financing steady (especially to SMEs) and required virtually no state aid. As a consequence, the local savings banks cushioned the impact of the financial crisis on the German economy, and their continued financing of firms is certainly a major factor in explaining the quick rebound of the German economy after 2010.

If taken together, the banking sector and the labour market institutions design a remarkably efficient system, geared towards the establishment of long run relationships in which the interests and the objectives (between entrepreneurs and workers, between banks and firms) were aligned.

But this effectiveness did not come without costs. From a macroeconomic point of view, profitability and competitiveness increased, but also precautionary savings, induced by a less generous welfare state, and by the increased uncertainty faced by workers. The “success” of the German export-led economy, that had a 9% current account surplus in 2016, is based on the compression of domestic demand, and on a labour market that is increasingly split in two, and in which inequality increased dramatically. The low unemployment that should make other countries envious hides a massive increase of the so-called working poor. (See figure 2 here)

I would push this even further: the Hartz Reform had a strong impact on labour market dualism and precariousness, but only a minor one in explaining the resilience of the economy. A recent CER policy brief makes a somewhat similar point.

Following the Jobs Act, the Italian labour market seems to be headed in a similar direction as the German one. The recent data released by ISTAT on labour market development certified the return of employed people to the pre-crisis peak (2008), thus marking, symbolically the end of the crisis. Yet, GDP is still 7% below its 2008 level, meaning that the increase of employment happened in low value added sectors (such as for example tourism and catering), and often with part-time contracts. These are typically sectors with low and very low wages, and stagnant productivity dynamics. At the same time, wages (but not employment) increase in manufacturing-export oriented sectors. The Italian labour market, in a sentence, is heading towards the same dualistic structure that characterizes the German one. This explains why, like in Germany, Italian domestic demand stagnates; why the increase in employment is obtained at the price of increased precariousness and of the working poor; why, finally, while the numbers say that the crisis is beyond us, the actual experience of households is often different. Italy, and to a minor extent Germany, are the best proof that employment and growth do not necessarily go hand in hand with increased well-being.

Focusing exclusively on labour market flexibility, Italy and in France only imported one element of the German “model”; and probably the one that is by far the least important. The German capacity to put in place long term relationships, the real key to economic resilience success, is lost in our countries.

Killing Them Softly?

Just a very quick and unstructured note on Greece. There is lots of confusion under the sky, and it seems to me that creditors are today advancing in sparse order.

Yesterday something rather upsetting happened, as the Eurogroup suspended bailout payments because Greece engaged in some extra expenditures. These are mostly targeted to pensioneers and to the Greek islands that had to endure unexpected costs linked to the refugee crisis. Unexpectedly, the Commission is siding with Greece, with Pierre Moscovici arguing that the country is on target, and that its effort has been remarkable so far. In fact, I have understood, Greece is doing so well that it overshot the target of structural surplus for 2016, and it it these extra resources that it is engaging in order to soft the impact of austerity.

And then there is the IMF, accused by Greece of pushing for more austerity, is also under attack from EU institutions (Eurogroup and Commission) for its refusal to join the bailout package. The Fund has hit back, in a somewhat irritual blog post signed by Maurice Obstfeld and Poul Thomsen (not just any two staffers) and seems not to be available to play the scapegoat for a program that in their opinion was born flawed. In fact, I think that more than to Greece, Obstfeld and Thomsen have written with the other creditors in mind.

I have two considerations, one on the economics of all this, one on the politics.

- I think I will side with the IMF on this. At least with the recent IMF. Since the very beginning The IMF has dubbed as irrealistic the bailout package agreed after the referendum of 2015 . The effort demanded to Greece (the infamous 3.5% structural surplus to be reached by 2018) was recognized to be self-defeating, and the IMF asked for more emphasis on reform, with in exchange a more lenient and realistic approach to fiscal policy: debt relief and much lower required suprluses (1.5% of GDP). In other words, the IMF seems to have learnt from the self-defeating austerity disaster of 2010-2014, and to have finally an eye to the macroeconomic consistency of the reform package. I still believe that the bailout should have been unconditional, and require reforms once the economy had recovered (sequencing, sequencing, and sequencing again). But still, at least the IMF now has a coherent position. Moscovici’s FT piece linked above also seems to go in the same direction, arguing that nothing more can be asked to Greece. It falls short of acknowledging that the package is unrealistic, but at least it avoids blaming the country. And then there is the Eurogroup, actually, Mr Dijsselbloem and Schauble (let’s name names), that did not move an inch since 2010, and fail to see that their demands are slowly (?) choking the Greek economy, stifling any effort to soften the hardship of the adjustment.

- The political consideration is that the hawks still give the cards, as they dominate the eurogroup. But they are more isolated now. Evidence is piling that the eurozone crisis has been mismanaged to an extent that is impossible to hide, and that the austerity-reforms package that the Berlin View has imposed to the whole eurozone is a big part of the explanation for the political disgregation that we see across the continent. The more nuanced position of the Commission, the IMF challenge to the policies dictated by the hawks, therefore represent an opportunity. There is a clear political space for an alternative to the Berlin View and to the disastrous policies followed so far. The question is which government will be willing (and able) to rise to the occasion. I am afraid I know the anwser.

Resilience? Not Yet

Last week the ECB published its Annual Report, that not surprisingly tells us that everything is fine. Quantitative easing is working just fine (this is why on March 10 the ECB took out the atomic bomb), confidence is resuming, and the recovery is under way. In other words, apparently, an official self congratulatory EU document with little interest but for the data it collects.

Except, that in the foreword, president Mario Draghi used a sentence that has been noticed by commentators, obscuring, in the media and in social networks, the rest of the report. I quote the entire paragraph, but the important part is highlighted

2016 will be a no less challenging year for the ECB. We face uncertainty about the outlook for the global economy. We face continued disinflationary forces. And we face questions about the direction of Europe and its resilience to new shocks. In that environment, our commitment to our mandate will continue to be an anchor of confidence for the people of Europe.

Why is that important? Because until now, a really optimistic and somewhat naive observer could have believed that, even amid terrible sufferings and widespread problems, Europe was walking the right path. True, we have had a double-dip recession, while the rest of the world was recovering. True, the Eurozone is barely at its pre-crisis GDP level, and some members are well below it. True, the crisis has disrupted trust among EU countries and governments, and transformed “solidarity” into a bad word in the mouth of a handful of extremists. But, one could have believed, all of this was a necessary painful transition to a wonderful world of healed economies and shared prosperity: No gain without pain. And the naive observer was told, for 7 years, that pain was almost over, while growth was about to resume, “next year”. Reforms were being implemented (too slowly, ça va sans dire) , and would soon bear fruits. Austerity’s recessionary impact had maybe been underestimated, but it remained a necessary temporary adjustment. The result, the naive observer would believe, would eventually be that the Eurozone would grow out of the crisis stronger, more homogeneous, and more competitive.

I had noticed a long time ago that the short term pain was evolving in more pain, and more importantly, that the EMU was becoming more heterogeneous precisely along the dimension, competitiveness, that reforms were supposed to improve. I also had noticed that as a result the Eurozone would eventually emerge from the crisis weaker, not stronger. More rigorous analysis ( e.g. here, and here) has recently shown that the current policies followed in Europe are hampering the long term potential of the economy.

Today, the ECB recognizes that “we face questions about the resilience [of Europe] to new shocks”. Even if the subsequent pages call for more of the same, that simple sentence is an implicit and yet powerful recognition that more of the same is what is killing us. Seven years of treatment made us less resilient. Because, I would like to point out, we are less homogeneous than we were in 2007. A hard blow for the naive observer.

Draghi the Fiscal Hawk

We are becoming accustomed to European policy makers’ schizophrenia, so when yesterday during his press conference Mario Draghi mentioned the consolidating recovery while announcing further easing in December, nobody winced. Draghi’s call for expansionary fiscal policies was instead noticed, and appreciated. I suggest some caution. Let’s look at Draghi’s words:

Fiscal policies should support the economic recovery, while remaining in compliance with the EU’s fiscal rules. Full and consistent implementation of the Stability and Growth Pact is crucial for confidence in our fiscal framework. At the same time, all countries should strive for a growth-friendly composition of fiscal policies.

During the Q&A, the first question was on precisely this point:

Question: If I could ask you to develop the last point that you made. Governor Nowotny last week said that monetary policy may be coming up to its limits and perhaps it was up to fiscal policy to loosen a little bit to provide a bit of accommodation. Could you share your thoughts on this and perhaps even touch on the Italian budget?

(Here is the link to Austrian Central Bank Governor Nowotny making a strong statement in favour of expansionary fiscal policy). Draghi simply did not answer on fiscal policy (nor on the Italian budget, by the way). The quote is long but worth reading

Draghi: On the first issue, I’m really commenting only on monetary policy, and as we said in the last part of the introductory statement, monetary policy shouldn’t be the only game in town, but this can be viewed in a variety of ways, one of which is the way in which our colleague actually explored in examining the situation, but there are other ways. Like, for example, as we’ve said several times, the structural reforms are essential. Monetary policy is focused on maintaining price stability over the medium term, and its accommodative monetary stance supports economic activity. However, in order to reap the full benefits of our monetary policy measures, other policy areas must contribute decisively. So here we stress the high structural unemployment and the low potential output growth in the euro area as the main situations which we have to address. The ongoing cyclical recovery should be supported by effective structural policies. But there may be other points of view on this. The point is that monetary policy can support and is actually supporting a cyclical economic recovery. We have to address also the structural components of this recovery, so that we can actually move from a cyclical recovery to a structural recovery. Let’s not forget that even before the financial crisis, unemployment has been traditionally very high in the euro area and many of the structural weaknesses have been there before.

Carefully avoiding to mention fiscal policy, when answering a question on fiscal policy, speaks for itself. In fact, saying that “Fiscal policies should support the economic recovery, while remaining in compliance with the EU’s fiscal rules” and putting forward for the n-th time the confidence fairy, amounts to a substantial approval of the policies followed by EMU countries so far. We should stop fooling ourselves: Within the existing rules there is no margin for a meaningful fiscal expansion of the kind invoked by Governor Nowotny. If we look at headline deficit, forecast to be at 2% in 2015, the Maastricht limits leave room for a global fiscal expansion of 1% of GDP, decent but not a game changer (without mentioning the fiscal space of individual countries, very unevenly distributed). And if we look at the main indicator of fiscal effort put forward by the fiscal compact, the cyclical adjusted deficit, the eurozone as a whole should keep its fiscal consolidation effort going, to bring the deficit down from its current level of 0.9% of GDP to the target of 0.5%.

It is no surprise then that the new Italian budget (on which Mario Draghi carefully avoided to comment) is hailed (or decried) as expansionary simply because it slows a little (and just a little) the pace of fiscal consolidation. Within the rules forcefully defended by Draghi, this is the best countries can do. As a side note, I blame the Italian (and the French) government for deciding to play within the existing framework. Bargaining a decimal of deficit here and there will not lift our economies out of their disappointing growth; and more importantly, on a longer term perspective, it will not help advance the debate on the appropriate governance of the eurozone.

In spite of widespread recognition that aggregate demand is too low, Mario Draghi did not move an inch from his previous beliefs: the key for growth is structural reforms, and structural reforms alone. He keeps embracing the Berlin View. The only substantial difference between Draghi and ECB hawks is his belief that, in the current cyclical position, structural reforms should be eased by accommodating monetary policy. This is the only rationale for QE. Is this enough to define him a dove?

Convergence, Where Art Thou?

A new Occasional Paper details the new methodology adopted by the Bank of Italy for calculating an index of price competitiveness, and applies it to the four largest eurozone economies.

I took the time to copy the numbers of table 3 in an excel file (let’s hope for the best), and to look at what happened since 2009. Here is the evolution of price competitiveness (a decrease means improved competitiveness):

I find this intriguing. We have been sold the story of Spain as the success story for EMU austerity as, contrary to other countries, it restored its external balance through internal devaluation. Well, apparently not. Since 2008 its price competitiveness improved, but less so than in the three other major EMU countries.

The reason must be that the rebalancing was internal to the eurozone, so that the figure does not in fact go against austerity nor internal devaluation. For sure, within eurozone price competitiveness improved for Spain. Well, think again…

This is indeed puzzling, and goes against anedoctical evidence. We’ll have to wait for the new methodology to be scrutinized by other researchers before making too much of this. But as it stands, it tells a different story from what we read all over the places. Spain’s current account improvement can hardly be related to an improvement in its price competitiveness. Likewise, by looking at France’s evolution, it is hard to argue that its current account problems are determined by price dynamics.

Without wanting to draw too much from a couple of time series, I would say that reforms in crisis countries should focus on boosting non-price competitiveness, rather than on reducing costs (in particular labour costs). And the thing is, some of these reforms may actually need increased public spending, for example in infrastructures, or in enhancing public administration’s efficiency. To accompany these reforms there is more to macroeconomic policy than just reducing taxes and at the same time cutting expenditure.

Since 2010 it ha been taken for granted that reforms and austerity should go hand in hand. This is one of the reasons for the policy disaster we lived. We really need to better understand the relationship between supply side policies and macroeconomic management. I see little or no debate on this, and I find it worrisome.

Smoke Screens

I have just read Mario Draghi’s opening remarks at the Brookings Institution. Nothing very new with respect to Jackson Hole and his audition at the European Parliament. But one sentence deserves commenting; when discussing how to use fiscal policy, Draghi says that:

Especially for those [countries] without fiscal space, fiscal policy can still support demand by altering the composition of the budget – in particular by simultaneously cutting distortionary taxes and unproductive expenditure.

So, “restoring fiscal policy” should happen, at least in countries in trouble, through a simultaneous reduction of taxes and expenditure. Well, that sounds reasonable. So reasonable that it is exactly the strategy chosen by the French government since the famous Jean-Baptiste Hollande press conference, last January.

Oh, wait. What was that story of balanced budgets and multipliers? I am sure Mario Draghi remembers it from Economics 101. Every euro of expenditure cuts, put in the pockets of consumers and firms, will not be entirely spent, but partially saved. This means that the short term impact on aggregate demand of a balanced budget expenditure reduction is negative. Just to put it differently, we are told that the risk of deflation is real, that fiscal policy should be used, but that this would have to happen in a contractionary way. Am I the only one to see a problem here?

But Mario Draghi is a fine economist, many will say; and his careful use of adjectives makes the balanced budget multiplier irrelevant. He talks about distortionary taxes. Who would be so foolish as not to want to remove distortions? And he talks about unproductive expenditure. Again, who is the criminal mind who does not want to cut useless expenditure? Well, the problem is that, no matter how smart the expenditure reduction is, it will remain a reduction. Similarly, even the smartest tax reduction will most likely not be entirely spent; especially at a time when firms’ and households’ uncertainty about the future is at an all-times high. So, carefully choosing the adjectives may hide, but not eliminate, the substance of the matter: A tax cut financed with a reduction in public spending is recessionary, at least in the short run.

To be fair there may be a case in which a balanced budget contraction may turn out to be expansionary. Suppose that when the government makes one step backwards, this triggers a sudden burst of optimism so that private spending rushes to fill the gap. It is the confidence fairy in all of its splendor. But then, Mario Draghi (and many others, unfortunately) should explain why it should work now, after having been invoked in vain for seven years.

Truth is that behind the smoke screen of Draghinomics and of its supposed comprehensive approach we are left with the same old supply side reforms that did not lift the eurozone out of its dire situation. It’ s the narrative, stupid!

The Lost Consistency of European Policy Makers

Just a quick note on something that went surprisingly unnoticed so far. After Draghi’s speech in Jackson Hole, a new consensus seems to have developed among European policy makers, based on three propositions:

- Europe suffers from deficient aggregate demand

- Monetary policy has lost traction

- Investment is key, both as a countercyclical support for growth, and to sustain potential growth in the medium run

My first reaction is, well, welcome to the club! Some of us have been saying this for a while (here is the link to a chat, in French, I had with Le Monde readers in June 2009). But hey, better late than never! It is nice that we all share the diagnosis on the Eurocrisis. I don’t feel lonely anymore.

What is interesting, nevertheless, is that while the diagnosis has changed, the policy prescriptions have not (this is why I failed to share the widespread excitement that followed Jackson Hole). Think about it. Once upon a time we had the Berlin View, arguing that the crisis was due to fiscal profligacy and insufficient flexibility of the economy. From the diagnosis followed the medicine: austerity and structural reforms, to restore confidence, competitiveness, and private spending.

Today we have a different diagnosis: the economy is in a liquidity trap, and spending stagnates because of insufficient expected demand. And the recipe is… austerity and structural reforms, to restore confidence, competitiveness, and private spending (in case you wonder, yes, I have copied-pasted from above).

Just as an example among many, here is a short passage from Mario Draghi’s latest audition at the European Parliament, a couple of weeks back:

Let me add however that the success of our measures critically depends on a number of factors outside of the realm of monetary policy. Courageous structural reforms and improvements in the competitiveness of the corporate sector are key to improving business environment. This would foster the urgently needed investment and create greater demand for credit. Structural reforms thus crucially complement the ECB’s accommodative monetary policy stance and further empower the effective transmission of monetary policy. As I have indicated now at several occasions, no monetary – and also no fiscal – stimulus can ever have a meaningful effect without such structural reforms. The crisis will only be over when full confidence returns in the real economy and in particular in the capacity and willingness of firms to take risks, to invest, and to create jobs. This depends on a variety of factors, including our monetary policy but also, and even most importantly, the implementation of structural reforms, upholding the credibility of the fiscal framework, and the strengthening of euro area governance.

This is terrible for European policy makers. They completely lost control over their discourse, whose inconsistency is constantly exposed whenever they speak publicly. I just had a first hand example yesterday, listening at the speech of French Finance Minister Michel Sapin at the Columbia Center for Global Governance conference on the role of the State (more on that in the near future): he was able to argue, in the time span of 4-5 minutes, that (a) the problem is aggregate demand, and that (b) France is doing the right thing as witnessed by the halving of structural deficits since 2012. How (a) can go with (b), was left for the startled audience to figure out.

Terrible for European policy makers, I said. But maybe not for the European economy. Who knows, this blatant contradiction may sometimes lead to adapting the discourse, and to advocate solutions to the deflationary threat that are consistent with the post Jackson Hole consensus. Maybe. Or maybe not.

Labour Costs: Who is the Outlier?

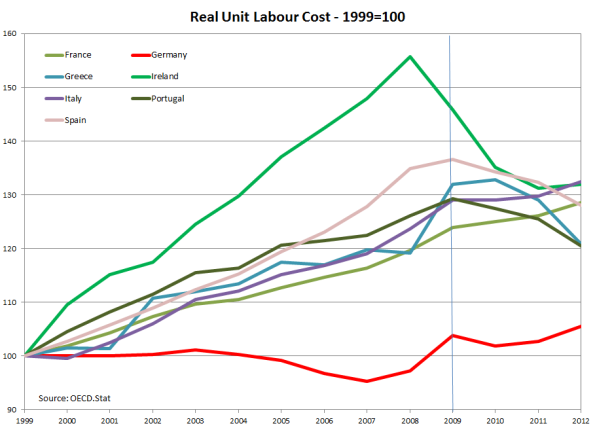

Spain is today the new model, together with Germany of course, for policy makers in Italy and France. A strange model indeed, but this is not my point here. The conventional wisdom, as usual, almost impossible to eradicate, states that Spain is growing because it implemented serious structural reforms that reduced labour costs and increased competitiveness. A few laggards (in particular Italy and France) stubbornly refuse to do the same, thus hampering recovery across the eurozone. The argument is usually supported by a figure like this

And in fact, it is evident from the figure that all peripheral countries diverged from the benchmark, Germany, and that since 2008-09 all of them but France and Italy have cut their labour costs significantly. Was it costly? Yes. Could convergence have made easier by higher inflation and wage growth in Germany, avoiding deflationary policies in the periphery? Once again, yes. It remains true, claims the conventional wisdom, that all countries in crisis have undergone a painful and necessary adjustment. Italy and France should therefore also be brave and join the herd.

Think again. What if we zoom out, and we add a few lines to the figure? From the same dataset (OECD. Productivity and ULC By Main Economic Activity) we obtain this:

It is unreadable, I know. And I did it on purpose. The PIIGS lines (and France) are now indistinguishable from other OECD countries, including the US. In fact the only line that is clearly visible is the dotted one, Germany, that stands as the exception. Actually no, it was beaten by deflation-struck Japan. As I am a nice guy, here is a more readable figure:

The figure shows the difference between change in labour costs in a given country, and the change in Germany (from 1999 to 2007). labour costs in OECD economies increased 14% more than in Germany. In the US, they increased 19% more, like in France, and slightly better than in virtuous Netherlands or Finland. Not only Japan (hardly a model) is the only country doing “better” than Germany. But second best performers (Israel, Austria and Estonia) had labour costs increase 7-8% more than in Germany.

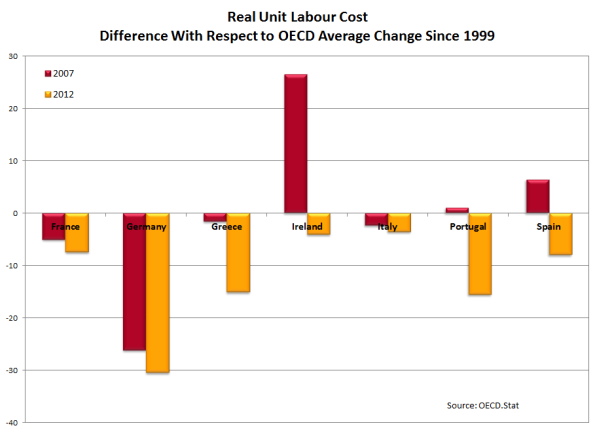

Thus, the comparison with Germany is misleading. You should never compare yourself with an outlier! If we compare European peripheral countries with the OECD average, we obtain the following (for 2007 and 2012, the latest available year in OECD.Stat)

If we take the OECD average as a benchmark, Ireland and Spain were outliers in 2007, as much as Germany; And while since then they reverted to the mean, Germany walked even farther away. It is interesting to notice that unreformable France, the sick man of Europe, had its labour costs increase slightly less than OECD average.

Of course, most of the countries I considered when zooming out have floating exchange rates, so that they can compensate the change in relative labour costs through exchange rate variation. This is not an option for EMU countries. But this means that it is even more important that the one country creating the imbalances, the outlier, puts its house in order. If only Germany had followed the European average, it would have labour costs 20% higher than their current level. There is no need to say how much easier would adjustment have been, for crisis countries. Instead, Germany managed to impose its model to the rest of the continent, dragging the eurozone on the brink of deflation.

What is enraging is that it needed not be that way.

Jean-Baptiste Hollande

le temps est venu de régler le principal problème de la France : sa production.

Oui, je dis bien sa production. Il nous faut produire plus, il nous faut produire mieux.

C’est donc sur l’offre qu’il faut agir. Sur l’offre !

Ce n’est pas contradictoire avec la demande. L’offre crée même la demande.

François Hollande – January 14, 2014

France is often pointed to as the “sick man of Europe”. Low growth, public finances in distress, increasing problems of competitiveness, a structural inability to reform its over-regulated economy. Reforms that, it goes without saying, would open the way to a new era of growth, productivity and affluence.

François Hollande has tackled the second half of his mandate subscribing to this view. In the third press conference since he became President, he outlined the main lines of intervention to revive the French economy, most notably a sharp reduction of social contributions for French firms (around € 30bn before 2017), financed by yet unspecified reductions in public spending. During the press conference, he justified this decision on the ground that growth will resume once firms start producing more. Thus, he tells us, “It is upon supply that we need to act. On supply! This is not contradictory with demand. Supply actually creates demand“. Hmmm, let me think. Supply creates demand. Where did I read this?

Read more

Competitive Structural Reforms

Mario Draghi, in an interview to the Journal du Dimanche, offers an interesting snapshot of his mindset. He (correctly in my opinion) dismisses euro exit and competitive devaluations as a viable policy choices:

The populist argument that, by leaving the euro, a national economy will instantly benefit from a competitive devaluation, as it did in the good old days, does not hold water. If everybody tries to devalue their currency, nobody benefits.

But in the same (short) interview, he also argues that

We remain just as determined today to ensure price stability and safeguard the integrity of the euro. But the ECB cannot do it all alone. We will not do governments’ work for them. It is up to them to undertake fundamental reforms, support innovation and manage public spending – in short, to come up with new models for growth. […] Taking the example of German growth, that has not come from the reduction of our interest rates (although that will have helped), but rather from the reforms of previous years.

I find it fascinating: Draghi manages to omit that German increased competitiveness mostly came from wage restraint and domestic demand compression, as showed by a current account that went from a deficit to a large surplus over the past decade. Compression of domestic demand and export-led growth, in the current non-cooperative framework, would mean taking market shares from EMU partners. This is in fact what Germany did so far, and is precisely the same mechanism we saw at work in the 1930s. Wages and prices would today take the place of exchange rates then, but the mechanism, and the likely outcome are the same. Unless…

Draghi probably has in mind a process by which all EMU countries embrace the German export-led model, and export towards the rest of the world. I have already said (here, here, and here) what I think of that. We are not a small open economy. If we depress our economy there is only so much the rest of the world can do to lift it through exports. And it remains that the second largest economy in the world deserves better than being a parasite on the shoulders of others…

As long as German economists are like the guy I met on TV last week, there is little to be optimist about…