Archive

On the Importance of Fiscal Policy

Last week’s data on EMU growth have triggered quite a bit of comments. I was intrigued by Paul Krugman‘s piece arguing (a) that in per capita terms the EMU performance is not as bad (he uses working age population, I used total population); and (b) that the path of the EMU was similar to that of the US in the first phase of the crisis; and (c) that divergence started only in 2011, due to differences in monetary policy (an impeccable disaster here, much more reactive in the US). Fiscal policy, Krugman argues, was equally contractionary across the ocean.

I pretty much agree that the early policy response to the crisis was similar, and that divergence started only when the global crisis went European, after the Greek elections of October 2009. But I am puzzled (and it does not happen very often) by Krugman’s dismissal of austerity as a factor explaining different performances. True, at first sight, fiscal consolidation kicked in at the same moment in the US and in Europe. I computed the fiscal impulse, using changes in the cyclically adjusted primary deficit. In other words, by taking away the cyclical component, and interest payment, we can obtain the closest possible measure to the discretionary fiscal stance of a government. And here is what it gives:

Krugman is certainly right that austerity was widespread in 2011 and in 2012 (actually more in the US). So what is the problem?

The problem is that fiscal consolidation needs not to be assessed in isolation, but in relation to the environment in which it takes place. First, it started one year earlier in the EMU (look at the bars for 2010). Second, expansion had been more robust in the US in 2008 and in 2009, thus avoiding that the economy slid too much: having been bolder and more effective in 2008-2010, continued fiscal expansion was less necessary in 2011-12.

I remember Krugman arguing at the time that the recovery would have been stronger and faster if the fiscal stance in the US had remained expansionary. I agreed then and I agree now: government support to the economy was withdrawn when the private sector was only partially in condition to take the witness. But to me it is just a question of degree and of timing in reversing a fiscal policy stance that overall had been effective.

I had made the same point back in 2013. Here is, updated from that post, the correlation between public and private expenditure:

| Correlation Between Public and Private Expenditure | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-2009 | 2010-2012 | 2013-2015 | |

| EMU | -0.96 | 0.73 | 0.99 |

| USA | -0.82 | -0.96 | -0.04 |

Remember, a positive correlation means that fiscal policy moves together with private expenditure, and fails to act countercyclically. The table tells us that public expenditure in the US was withdrawn only when private expenditure could take the witness, and never was procylclical (it turned neutral in the past 2 years). Europe is a whole different story. Fiscal contraction began when the private sector was not ready to take the witness; the withdrawal of public demand therefore led to a plunge in economic activity and to the double dip recession that the US did not experience. Here is the figure from the same post, also updated:

To sum up: the fiscal stance in the US was appropriate, even if it changed a bit too hastily in 2011. In Europe, it was harmful since 2010.

And monetary policy in all this? It did not help in Europe. I join Krugman in believing that once the economy was comfortably installed in the liquidity trap Mario Draghi’s activism while necessary was (and is) far from sufficient. Being more timely, the Fed played an important role with its aggressive monetary policy, that started precisely in 2012. It supported the expansion of private demand, and minimized the risk of a reversal when the withdrawal of fiscal policy begun. But in both cases I am unsure that monetary policy could have made a difference without fiscal policy. Let’s not forget that a first round of aggressive monetary easing in 2007-2008 had been successful in keeping the financial sector afloat, but not in avoiding the recession. This is why in 2009 most economies launched robust fiscal stimulus plans. I see no reason to believe that, in 2010-2012, more appropriate and timely ECB action would have made a big difference. The problem is fiscal, fiscal, fiscal.

Fed Debates and the EMU Technocratic Illusion

Thanks to the invaluable Economist’s View, I have read with lots of interest the speech that newly appointed Federal Reserve Board Member Lael Brainard gave last Monday. The speech is a plea for holding on rate rises, and uses a number of convincing arguments. Much has been said on the issue (give a look at comments by Tim Duy and Paul Krugman). I have little to add, were it not for the point I made a number of times, that the extraordinarily difficult task of central bankers would be made substantially easier if fiscal policy were used more actively.

What I’d like to express here is my jealousy for the discussions (and the confrontation) that we observe in the US. These discussions are a sideproduct, a very positive one if you ask me, of the institutional design of the Fed. I just returned from a series of engaging policy meetings on central bank policy in Costa Rica, facilitated by the local ILO office, where I pleaded for the introduction of a dual mandate.

I wrote a background paper (that can be seen here) in which my main argument is that a central bank following a dual mandate will always be able to take an aggressive stance on inflation, if it deems it necessary to do so. Appropriate choice of the weights given to employment and inflation would allow incorporation of any combination of the two objectives. A good case in point are the United States, where the Federal Reserve under Chairman Volcker embarked on a bold disinflation program in the early 1980s when the country had just adopted the dual mandate. No choice of weights, on the other hand, would allow a central bank following an inflation targeting mandate to explicitly target employment as well. Thus, the dual mandate can embed inflation targeting strategies, while the converse is not true. In terms of policy effectiveness, therefore, the dual mandate is a superior institutional arrangement.

I also cited evidence showing, and here we come at my jealousy for the Fed, that inflation targeting central banks, like the ECB, de facto target the output gap, but timidly and without explicitly saying so. This leads to low reactivity and opaque communication, that hamper the capacity of central banks to manage expectations and effectively steer the economy. I am sure that those who followed the EMU policy debate in the past few years will know what I am talking about.

One may argue that the cacophony currently characterizing the Federal Reserve Board is hardly positive for the economy, and that in terms of managing expectations, lately, the Fed did not excel. This is undeniable, and is the result of the Fed groping its way out of unprecedented policy measures. The difference with the ECB is that for the Fed the opacity results from an ongoing debate on how to best attain an objective that is clear and shared. We are not there yet, but the debate will eventually lead to an unambiguous (and hopefully appropriate) policy choice. The ECB opacity, is intrinsically linked to the confusion between its mandate and its actual action, and as such it cannot lead to any meaningful discussion, but just to legalistic disputes on the definition of price stability, of how medium is the medium term and the like.

And I can now come to my final point: a dual mandate has the merit to let the political nature of monetary policy emerge without ambiguities. It is indeed true that monetary policy with a dual mandate requires hard choices, as the ones that are debater these days, and hence is political in nature. The point is, that so is monetary policy with a simple inflation targeting objective. The level of inflation targeted, and the choice of the instruments to attain it, are all but neutral in terms of their consequences on the economy, most notably on the distribution of resources among market participants. Thus, an inflation targeting central bank is as political in its actions as a bank following a dual mandate, the only difference being that In the former case the political nature of monetary policy is concealed behind a technocratic curtain.

The deep justification of exclusive focus on price stability can only lie in the acceptance of a neoclassical platonic world in which powerless governments need to make no choice. Once we dismiss that platonic view, monetary policy acquires a political role, regardless of the mandate it is given. A dual mandate has the merit of making this choice explicit, and hence to dispel the technocratic illusion.

I am not saying there would be no issues with the adoption of a dual mandate. The institutional design should be carefully crafted, in order to ensure that independence is maintained, and accountability (currently very low indeed) is enhanced. What I am saying is that after seven years (and counting) of dismal economic performance, and faced with strong arguments in favour of a broader central bank mandate, EMU policy makers should be engaged in discussions at least as lively as the ones of their counterparts in Washington. And yet, all is quiet on this side of the ocean… Circulez y a rien à voir

Does Price Stability Entail Financial Stability?

I reproduce here a post I wrote with Paul Hubert, published on the blog de l’OFCE in English and in French.

Paul Krugman raises the very important issue of the impact of monetary policy on financial stability. He starts with the well-known observation that, contrary to the predictions of some, expansionary monetary policy did not lead to inflation during the current crisis. He then continues arguing that tighter monetary policy would not necessarily guarantee financial stability either. If the Fed were to revert to a more standard Taylor rule, financial stability would not follow. As Krugman aptly argues, “That rule was devised to produce stable inflation; it would be a miracle, a benefaction from the gods, if that rule just happened to also be exactly what we need to avoid bubbles.“

Krugman in fact takes position against the “conventional wisdom”, which has been widespread in academic and policy circles alike, that a link exists between financial and price stability; therefore the central bank can always keep in check financial instability by setting an appropriate inflation target.

The global financial crisis is a clear example of the fallacy of this conventional wisdom, as financial instability built up in a period of great moderation. A recent analysis by Blot et al shows that the crisis is no exception, as over the past few decades, in the US and the Eurozone, the link between price and financial stability has been unclear and moreover unstable over time, as shown on the following figure.

We therefore subscribe to Krugman’s view that financial stability should be targeted by combining macro- and micro-prudential policies, and that inflation targeting is largely insufficient. In another work, Blot et al argue that the ECB should be endowed with a triple mandate for financial and macroeconomic stability, along with price stability. They further argue that the ECB should be given the instruments to effectively pursue these three, sometimes conflicting objectives.

Wrong Debates

Paul Krugman has a short post on the Eurozone, today (I’d like him to write more about us; he has been too America-centered lately), pointing out that the myth of fiscal profligacy is, well, just a myth. in fact, he argues, the only fiscally irresponsible country, in the years 2000 was Greece. It is maybe worth reposting here a figure that from an old piece of this blog, that since then made it into all my classes on the Euro crisis:

The figure shows the situation of public finances in 2007, against the Maastricht benchmark (3% deficit and 60% debt) before the crisis hit. As Krugman says, only one country of the so-called PIIGS (the red dots) is clearly out of line, Greece. Portugal is virtually like France, and Spain and Ireland way better than most countries, including Germany. Italy has a stock of old debt, but its deficit in 2007 is under control.

So Krugman is right in reminding us that fiscal policy per se was not a problem before the crisis; And yet, what he calls fiscal myths, have shaped policies in the EMU, with a disproportionate emphasis on austerity. And even today, when economists overwhelmingly discuss unconventional measures available to the ECB to contrast deflation, fiscal policy is virtually absent from the debate and continued fiscal consolidation is taken for granted. I will write more on this in the next days, but it is striking how we aim at the wrong target.

What is Mainstream Economics?

Paul Krugman and Simon Wren-Lewis have been widely criticized (for example here) as defending “mainstream” economics that spectacularly failed during the crisis (and before).

My (very short) take on this: I do believe that Krugman has a point, a very good one, when claiming that standard textbook analysis is (almost) all you need to understand the current crisis, and to implement the correct policy solutions.

The point is what we define as “textbook analysis”. Krugman refers to IS-LM models. But these, that starting in the 1980s virtually disappeared from graduate curricula because supposedly too simplistic, not grounded on optimization, not intertemporal, and so on and so forth.

I personally was exposed to these ideas in my undergraduate studies in Italy, and I still teach them (besides using them to discuss the crisis with my students). But they were nowhere to be found during my graduate studies at Columbia (certainly not a freshwater school). None of the macro I studied in graduate school (Real Business Cycle models, or their fixed-price variant proposed by New Keynesians) as interesting as it was intellectually, could give me insight on the crisis. I simply do not need to use it.

The IS-LM model with minor amendments (most notably properly accounting for expectations to deal among other things with liquidity traps) remains a powerful tool to understand current phenomena. The problem is that it is not mainstream at all. What bothers me in Krugman’s post is the word “standard”, not “textbook analysis”.

Lilliput in Deutschland

Following the widely discussed U.S. Treasury report on foreign economic and currency policies, that for the first time blames Germany explicitly for its record trade surpluses, I published an op-ed on the Italian daily Il Sole 24 Ore (in Italian), comparing Germany with China. My argument there is the following:

- Before the crisis the excess savings of China and Germany, the two largest world exporters, contributed to the growing global imbalances by absorbing the excess demand of the U.S. and of other economies (e.g., the Eurozone periphery) that made the world economy fragile. (more here)

- In the past decade, China seems to have grasped the problems yielded by an export-led growth model, and tried to rebalance away from exports (and lately investment) towards consumption (more here). The adjustment is slow, sometimes incoherent, but it is happening.

- Germany walked a different path, proudly claiming that the compression of domestic demand and increased exports were the correct way out of the crisis (as well as the correct model for long-term growth)

- Germany’s economic size, its position of creditor, and its relatively better performance following the sovereign debt crisis, (together with a certain ideological complicity from EC institutions) allowed Germany to impose the model based on austerity and deflation to peripheral eurozone countries in crisis.

- Even abstracting from the harmful effects of austerity (more here), I then pointed out that the German model cannot work for two reasons: The first is the many times recalled fallacy of composition): Not everybody can export at the same time. The second, more political, is that by betting on an export-led growth model Germany and Europe will be forced to rely on somebody else’s growth to ensure their prosperity. It is now U.S. imports; it may be China’s tomorrow, and who know who the day after tomorrow. This is of course a source of economic fragility, but also of irrelevance on the political arena, where influence goes hand in hand with economic power. Choosing the German economic model Europe would condemn itself to a secondary role.

I would add that the generalization of the German model to the whole eurozone is leading to increasing current account surpluses. Therefore, this is not simply a European problem anymore. By running excess savings as a whole, we are collectively refusing to chip in the ongoing fragile recovery. The rest of the world is right to be annoyed at Germany’s surpluses. We continue to behave like Lilliput, refusing to play our role of large economy.

Let me conclude by noticing that today in his blog Krugman shows that sometimes a chart is worth a thousand (actually 748) words:

Living in Terror of Dead Economists

Kenneth Rogoff has a piece on the Project Syndicate that is revealing of today’s intellectual climate. What does he say?

- The eurozone problems are structural, and stem from a monetary and economic integration that was not followed (I’d say accompanied) by fiscal integration (a federal budget to be clear). Hard to disagree on that

- Without massive debt write-downs, no reasonable solution to the current mess seems feasible. Hard to disagree on that as well

- Some more inflation would be desirable, to bring down the value of debt. Hard to disagree on that as well.

In a sentence, intra eurozone imbalances are the source of the current crisis. Could not agree more…

Unfortunately, Rogoff does not stop here, but feels the irrepressible urge to add that

Temporary Keynesian demand measures may help to sustain short-run internal growth, but they will not solve France’s long-run competitiveness problems […] To my mind, using Germany’s balance sheet to help its neighbors directly is far more likely to work than is the presumed “trickle-down” effect of a German-led fiscal expansion. This, unfortunately, is what has been lost in the debate about Europe of late: However loud and aggressive the anti-austerity movement becomes, there still will be no simple Keynesian cure for the single currency’s debt and growth woes.

The question then arises. Who ever thought that a more expansionary stance in the eurozone would solve the French structural problems? And at the opposite, why would recognizing that France has structural problems make it less urgent to reverse the pro-cyclical fiscal stance of an eurozone that is desperately lacking domestic demand? Let me try to sort out things here. This is the way I see it: Read more

Cockroach Ideas and Weak Arguments

Helene Mees in a Project Syndicate Comment weighs into the dispute between Paul Krugman and the Commission officials, siding with Rehn and his people.

Mees’ criticism of Krugman is two-sided. First, she argues, Krugman omits to say that the OMTs program is subject to heavy conditionality, and that the signature of the fiscal compact was a necessary precondition for the adoption of the program. I don’t get it. The ECB is very vocal on austerity and on structural reforms, and it is clear that the OMTs program was adopted only at the very last minute, facing the perspective of eurozone collapse. A number of economists, including myself, welcomed the OMTs while criticizing the heavy conditionality attached to it. The very fact that the OMTs was reluctantly adopted shows that even austerity partisans cannot deny the fact that the EMU is desperately lacking a proper lender of last resort, of which the OMT is a pale surrogate. The more non-Keynesian institutions are forced to adopt Keynesian solutions, the more Krugman’s point is vindicated. I fail to see how the opposite could be true. Read more

Stones Keep Raining

Update January 2017: I redid the figure with more recent data

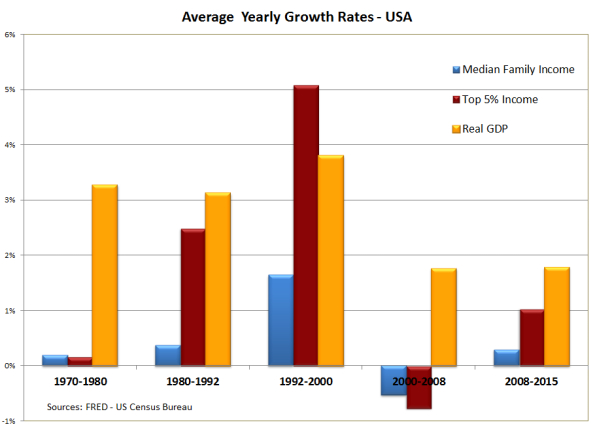

Paul Krugman hits hard on one of the most cherished american myths, the golden years of Reaganomics. He shows that using the middle class as a benchmark (the median family income of the economy), the Reagan decade saw a disappointing performance; this, not only if compared to the longest expansion in post war history, during the Clinton presidency, but also with respect to the much less glorious 1970s.

But, maybe, Krugman is telling a story of inequality, and not of sluggish growth. The fact that median income did not grow much during the Reagan years may not mean that growth was not satisfactory, but simply that somebody else grasped the fruits.

For curiosity, I completed his figure with average yearly growth rates for two other series: Income of the top 5% of the population, and the growth rate of the economy.

Well, it turns out that Reaganomics yielded increasing inequality and unsatisfactory growth. And well beyond that, median income consistently under-performed economic growth in the past forty years.

What seems extremely robust is the performance of the top 5% of the population. Their income increased significantly more than output over the past decades. It is striking in particular, how the very wealthy managed to cruise through the current crisis, when income of the middle class was slashed.

Nothing new, Ken Loach in 1993 said it beautifully: it is always raining stones on the working class. But I guess it does no harm to remind it from time to time…

Bringing Krugman to Europe

Well, not him, actually (I wish I could); I need to content myself with his latest post on austerity. Krugman argues that austerity is happening (it is trivial, but he needs repeating over and over again), showing that in the US expenditure as a share of potential GDP is back to its pre-crisis level (while unemployment remains too high, and growth stagnates).

I replicated his figure including some European countries, and with slightly different data. I took OECD series on cyclically adjusted public expenditure, net of interest payment. This is commonly taken as a rough measure of discretionary government expenditure. I also re-based it to 2008, as most stimulus plans were voted and implemented in 2009. Here is what it gives: Read more