Archive

Germany’s longing for the Ancien Régime is a Threat for Europe

Note: this is a rough translation of a piece published on the Italian neswpaper Domani, with a few edits and additions.

While the campaign for the election captures all the attention of the Italian establishment, we should not stop looking beyond our borders. In particular, the lack of interest in what is happening in Germany is striking and worrisome. The difficulties Europe’s largest economy is experiencing will in fact have far more significant consequences for many European countries than their domestic political struggles.

Last week, the ministry of economy and ecological transition (headed by the vice-chancellor and number two of the Green party, Robert Habeck) published a report on the reform of the stability pact, which, although we tend to forget it, will be THE topic of the coming months. The guiding principles for reform that the report outlines are basically a re-proposal of the existing rule, as if the disasters of the sovereign debt crisis and the Covid tsunami were a parenthesis to be closed as soon as possible by returning to the old world.

Under a gleaming hood, the German engine has been in crisis for years

There will be time to return to the inadequacy of this proposal (Carlo Clericetti does it well in the Italian magazine Micromega) and to the issue of European governance. What I would like to emphasise here is that the German elites, with this frenzy to return to the past, do not seem to fully grasp at least two things: First, the fact that after the experience of the last ten years it is not possible to return to an idea of economic policy for which the only beacon is fiscal discipline, neglecting public investment, industrial policy, social protection and so on. Second, and this is more surprising, they do not grasp the fact that the German growth model seems to have hit its boundaries. As a reminder, we are talking about a model aiming at export-led growth, that was based on the one hand on the compression of domestic demand (with wages that for decades grew much less than productivity); on the other hand it was based on an export sector that took advantage of both the dualism of the labour market and of value chains rooted in the countries of the former Soviet bloc. Germany could therefore import intermediate goods and low-cost components and re-export finished products, often with a high technological content, to non-European markets. This is the main reason why it remained a manufacturing power while most advanced countries had to cope with de-industrialisation and relocation.

Many, including myself have criticised this model, which during the sovereign debt crisis Germany successfully managed to generalise to the rest of the eurozone. In 2020, in concluding an essay on Europe, I pointed out how that model has come to an end. The public and private investment deficit, the result of decades of self-imposed frugality, has progressively depleted the capital stock and reduced the competitiveness of German industry. Meanwhile, while the growth of emerging countries has helped to provide outlets for German goods, it has also seen these countries develop high value-added production that competes with German exporting firms. But there is more: I also noted that the progressive distortion of the ordoliberal model, the increase in inequality and precariousness (which contributes to demographic stagnation and to the ageing of population), and the growing dependence on foreign demand, more problematic than ever in an increasingly uncertain geopolitical context, have all contributed to making Germany a giant with feet of clay.

A Giant with Feet of Clay

Feet of clay that today are cracking. The bottlenecks that appeared during and after the pandemic, due to lockdowns and to the recomposition of global supply and demand, have (not surprisingly) proved to be more persistent than many expected. Furthermore, the acceleration of investment in the ecological transition, obviously welcome and all too late, creates shortages particularly in sectors that are key for the German economy, such as the automotive. Finally, geopolitical tensions, the slowdown in emerging economies, and of course the war in Ukraine greatly reduce the outlets for the German export sector and have laid bare the short-sightedness of the past German leadership’s choice to rely on Russian oil and gas, admittedly reducing costs, but creating a dependency for which the country is now paying the price. It is important, however, to emphasise again that the events of the last two years have only come to add to the structural problems of a model of growth and organisation of production that was beginning to show its limits even before the pandemic.

The German elites at a crossroads

In 2020, I concluded my essay by stating that the crisis of the German model could have been an opportunity for Europe, as it would have forced Germany to worry about the imbalances within the eurozone, to promote public and private investment, to rethink industrial policy, to support (German and European) domestic demand; not out of altruism, but to create a stable European market in an international context that had become structurally uncertain and turbulent. The heartfelt support for Next Generation EU seemed to confirm the feeling that something had changed in Germany. The recent turn of the German debate is therefore worrisome and should be looked at closely. Habeck’s paper and the recent stances of the Minister of Finances, the liberal Lindner, point to a kind of “ostrich syndrome” of the German elites, who seem to long for a return to the past in order not to have to deal with the structural problems of Germany and of European integration. If this tendency prevails, not only the German citizens but the whole of Europe, which will slip into irrelevance, will pay the price in the coming years. On the contrary, representatives of the German government at European tables need to be called upon to contribute to the rethinking of industrial and energy policy and public investment policies, to the development of a European welfare state, to the definition of budget rules that allow for active and sustainable policies, to the development of the internal market, to the completion of the banking union, and the list could go on. In short, an ambitious and wide-ranging European discussion is needed to make the German elites look away from their navels and try to restore Europe’s centrality at a time of great geopolitical turbulence (which will certainly extend well beyond the war in Ukraine). France and Italy, because of their size and the influence they have had in Europe in the recent past, would obviously play a key role in countering the return to the past of the German elites. This is why the absence of European issues from the (pre-electoral) Italian and (post-electoral) French debate cannot but cause concern.

A German Model?

Tomorrow Germany votes, and there is little suspense, besides the highly symbolic question of whether the far right will make it into the Bundestag.

Angela Merkel will be Chancellor for the fourth time, marking a long period of political and policy stability. In the past fifteen years Germany emerged as the model to follow for the other large economies. For since its economy has performed better, in terms of growth and unemployment, than France or Italy.

I have at discussed at length, here and elsewhere, the costs of the German success in terms of global imbalances and uncooperative behaviours. Last week I wrote a piece for the newly born magazine LuissOpen (Ad: Follow it on twitter! There is plenty of interesting content well beyond economics! End of Ad).

The piece lists, in a non exhaustive way, a number of weaknesses that can be spotted behind the shining macroeconomic results, and also argues that there is much more than labour market liberalization behind a successful economic model (including in Germany).

The original piece can be found here (and here in Italian). I copy and paste it below

Three months after his commencement, Emmanuel Macron delivered last week one of the most important, and controversial, promises of his agenda. The loi travail that will become operational in the next few weeks mostly deals employment protection, which is weakened especially for small and medium enterprises. The aim is to lift constraints for firms hiring, and thus increase employment. This first set of norms should be followed in the next weeks or months by norms aimed at improving training and employability of unemployed workers. Once completed, the package would be the French version of the flexicurity that Scandinavian countries put in place in the past, with different degrees of success.

Without entering into the details of the law, the set of norms approved by the French government, just as the Italian Jobs Act voted in 2014, is a bold step towards the flexibilization of labour market relations that Germany has in place since the early years 2000, with the so-called “Hartz Reforms”. The German experience, and to a minor extent the first few years of application of the Job Act, can help understand how the French labour market could evolve in the next few years.

Germany in fact sets itself as an example. The argument goes that the reforms it implemented in 2003-2005, did liberalize labour markets, and since then, with the exception of the first years of the crisis, unemployment has been steadily decreasing. But in fact, this is a misleading example, because the Hartz reforms were embedded in a complex institutional setting, which goes well beyond labour market flexibility.

First, an important segment of the German labour market, the one linked to manufacturing and business services, has always been ruled by long-term agreements between employers, workers, and local work councils. For these insider workers a system of work relations was in place, in which highly paid workers acquired skills through vocational training (within or outside the firm), and were protected by an all-encompassing welfare system. Vocational training created robust bonds between the firms, that had often invested substantial resources in the training, and the workers, whose specific skills could not easily be transferred to other sectors or even to other firms.

At the turn of the century, globalized markets coupled with the aftermath of the reunification, exerted a serious pressure for a restructuring of labour relations. This restructuring happened through a consensus process that did not involve the government, and kept untouched the bond between the firm and the worker created by vocational training.

The mutual interest in preserving the long-term relationship between workers and firms in the insider markets, led to agreements aimed at reducing costs or to increase productivity without increasing turnover or reducing average job tenure. These agreements could involve on the workers’ side labour sharing, flexibility in hours and in labour mobility, wage concessions, reductions in absenteeism. In exchange for this, firms would guarantee continued investments in innovation and in the (vocational) training of workers, and job security.

It is crucial to understand that the Hartz reform did not touch the insiders market (manufacturing, finance, insurance and business, etc), that as we just said had already begun restructuring without government intervention. The reform made the welfare system less generous, while allowing access to benefits even for workers with low earnings, thus de facto introducing incentives to low-paid jobs. Furthermore, it liberalized temporary work contracts, and made more flexible a few sectors subject to competition from posted workers (i.e. construction).

The combined result of reforms and endogenous restructuring yielded a spike in part time jobs, and an increase of employment. But it also widened the gap in earnings and in protection between workers in the export-oriented sectors and the others.

The second feature of the German system that made it resilient during the crisis is the existence of a dense network of local public savings banks (the Sparkassen). Savings bank were a defining feature of the banking sectors of a number of European countries (e.g. Spain, Italy), but have progressively become marginal. Germany is therefore an exception in that its local savings banks are still a pillar of its economy.

Local savings banks have specific public interest missions, as they are involved in the development of local communities, and in financing households and firms (in particular SMEs). The law only allows operation within the region of competence, which shields them from competition while keeping them close to their stakeholders. Similarly, the ambit of their operations is limited (for example, they face limits in their capacity to engage in securities trading or in excessively risky financing).

To avoid that these limitations hamper their effectiveness and their solidity, the banks work as a network among them. The network exhibits economies of scale and of scope, while remaining close, in its individual components, to local communities. Furthermore, the existence of solidarity mechanisms (rescue funds) ensures that temporary difficulties of a bank are tackled without spreading contagion.

The major private commercial banks, very active in international markets, did suffer like in most other countries, were a drain on public finances, and drastically contracted their lending to the real sector. The Sparkassen on the other hand kept their financing steady (especially to SMEs) and required virtually no state aid. As a consequence, the local savings banks cushioned the impact of the financial crisis on the German economy, and their continued financing of firms is certainly a major factor in explaining the quick rebound of the German economy after 2010.

If taken together, the banking sector and the labour market institutions design a remarkably efficient system, geared towards the establishment of long run relationships in which the interests and the objectives (between entrepreneurs and workers, between banks and firms) were aligned.

But this effectiveness did not come without costs. From a macroeconomic point of view, profitability and competitiveness increased, but also precautionary savings, induced by a less generous welfare state, and by the increased uncertainty faced by workers. The “success” of the German export-led economy, that had a 9% current account surplus in 2016, is based on the compression of domestic demand, and on a labour market that is increasingly split in two, and in which inequality increased dramatically. The low unemployment that should make other countries envious hides a massive increase of the so-called working poor. (See figure 2 here)

I would push this even further: the Hartz Reform had a strong impact on labour market dualism and precariousness, but only a minor one in explaining the resilience of the economy. A recent CER policy brief makes a somewhat similar point.

Following the Jobs Act, the Italian labour market seems to be headed in a similar direction as the German one. The recent data released by ISTAT on labour market development certified the return of employed people to the pre-crisis peak (2008), thus marking, symbolically the end of the crisis. Yet, GDP is still 7% below its 2008 level, meaning that the increase of employment happened in low value added sectors (such as for example tourism and catering), and often with part-time contracts. These are typically sectors with low and very low wages, and stagnant productivity dynamics. At the same time, wages (but not employment) increase in manufacturing-export oriented sectors. The Italian labour market, in a sentence, is heading towards the same dualistic structure that characterizes the German one. This explains why, like in Germany, Italian domestic demand stagnates; why the increase in employment is obtained at the price of increased precariousness and of the working poor; why, finally, while the numbers say that the crisis is beyond us, the actual experience of households is often different. Italy, and to a minor extent Germany, are the best proof that employment and growth do not necessarily go hand in hand with increased well-being.

Focusing exclusively on labour market flexibility, Italy and in France only imported one element of the German “model”; and probably the one that is by far the least important. The German capacity to put in place long term relationships, the real key to economic resilience success, is lost in our countries.

The End of German Hegemony. Really?

I was puzzled by Daniel Gros’ recent Project Syndicate piece, in which he claims that Germany’s dominance of the EMU may be coming to an end. Gros’ argument is based on two facts. The first is the slowing growth rate of Germany, that seems to be heading towards the pre-crisis “normal” of slow growth (Germany grew less than EMU average for most of the period 1999-2007). The second, more geo-political, is the lack of willingness (or of capacity) to manage, the crises that face the EU (in particular the refugees crisis).

Gros concludes that this loss of influence is dangerous, because Germany will not be able to resist the changes in policies that are pushed by peripheral countries and by the ECB. Of course, implicit in this statement, is Gros’ belief that these policies were necessary and useful.

I welcome the recognition that Germany has steered the EMU since the beginning of the crisis. Those of us talking about the Germanification of Europe have been decried until very recently. Yet, I do not share, not at all, Gros view.

True, Germany’s growth is slowing down. These are the risks of an export-led growth model: countries are not masters of their own fate. Germany stayed clear from the peripheral countries’ crisis (that it contributed to create) by turning to the US and to emerging economies as markets for its exports. But now that these countries are also having problems, the limits of jumping on other countries’ shoulders to grow, become evident. I am surprised by Gros’ surprise, as this was evident from the very beginning.

But here I do not want to reiterate my criticisms of the export-led model, starting from the fallacy of composition. Instead, I would like to challenge Gros’ argument that Germany influence is waning. I would say on the contrary that the Germanification of the eurozone is almost complete.

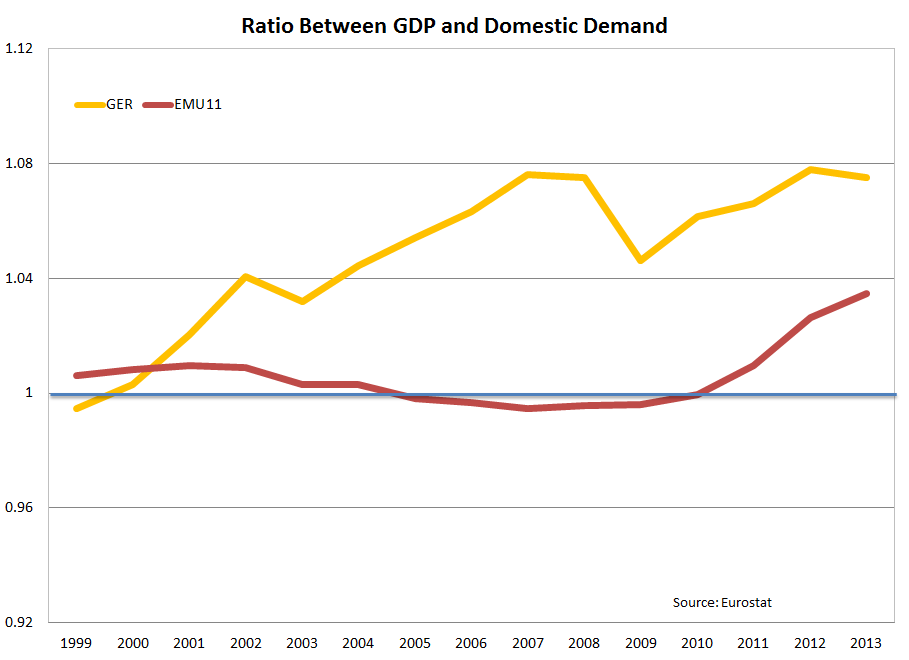

I took a few macroeconomic variables, and contrasted Germany with the remaining 11 EMU members. Let’s start with (missing) domestic demand, a defining characteristic of the export-led growth model:

Since 2007, the yellow line (EMU11) and the red line (Germany) converged, mostly because domestic demand in the rest of the EMU was reduced. This led of course to an increased reliance of the EMU as a whole on exports. The EMU as a whole had an overall balanced external position in 2007, while it has a substantial current account surplus today (the EMU12 went from 0.5% to 3.4 projected for 2016. Germany went from 7% to 7.7%). In other words, the EMU11 joined Germany on the shoulders of the rest of the world.

Austerity has of course much to be blamed for this compression of domestic demand: Just look at government balances (net of interest payments):

True, the difference between Germany and the rest of EMU is today larger than in 2007. But since Germany and the Troika took the driving seat in 2010, government balances of the EMU11 have been steadily converging to surplus, and they are not going to stop in the foreseeable horizon (the Commission forecasts go until 2016).

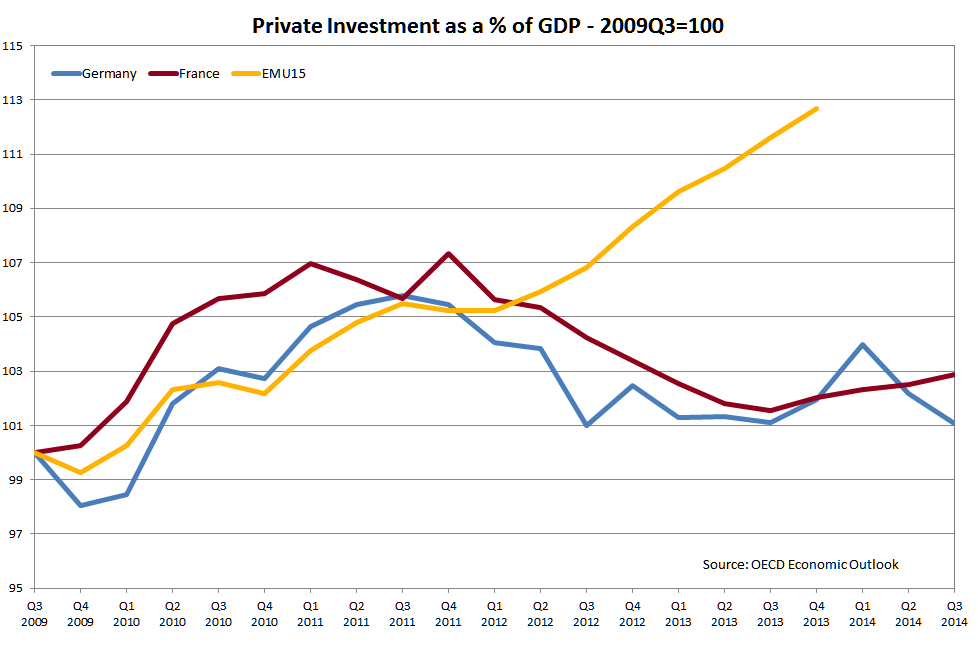

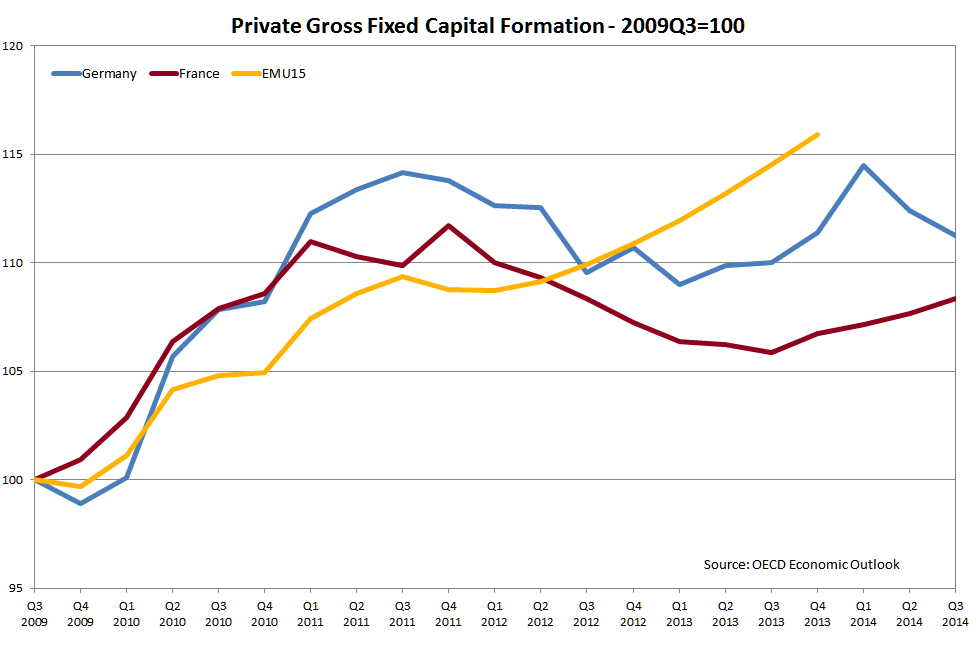

Finally, if we look at one of the main drivers of growth, investment, the picture is the same.

Be it private or public, the EMU11 Gross Fixed Capital Formation has been converging towards the (excessively low) German level (I did not draw the differences, not to clutter the figure).

And of course, there are labour costs, for which convergence to Germany was brutal, even if the latter, rather than EMU peripheral countries, were the outlier. To summarize, during the crisis the difference between Germany and the rest of the EMU was substantially reduced, and will continue to be in the next years:

The difference was reduced for all variables, except for government deficit. Self-defeating austerity slowed down the convergence. But private expenditure, in particular investment, more than compensated.

So, if I were Gros, I would not worry too much. The Germanification of Europe is well on its way. If Germany does not go to the EMU11 (it definitely does not!), the EMU11 keeps going to Germany.

But as I am not Gros, I worry a lot.

Mr Sinn on EMU Core Countries’ Inflation

Two weeks ago I received a request from Prof Sinn to make it known to my readers that he feels misrepresented by my post of September 29. Here is his very civilized mail, that I publish with his permission:

Dear Mr. Saraceno,

I have just become acquainted with your blog: https://fsaraceno.wordpress.com/2014/09/29/draghi-the-euro-breaker/. You misrepresent me here. In my book The Euro Trap. On Bursting Bubbles, Budgets and Beliefs, Oxford University Press 2014, and in many other writings, I advise against extreme deflation scenarios for southern Europe because of the grievous effects upon debtors. I explicitly draw the comparison with Germany in the 1929 – 1933 period. I advocate instead a mixed solution with moderate deflation in southern Europe and more inflation in northern Europe, Germany in particular. In addition, I advocate a debt conference for southern Europe and a “breathing currency union” which allows for temporary exits of those southern European countries for which the stress of an internal adjustment would be unbearable. You may also wish to consult my paper “Austerity, Growth and Inflation: Remarks on the Eurozone’s Unresolved Competitiveness Problem”, The World Economy 37, 2014, p. 1-1, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/twec.2014.37.issue-1/issuetoc, in which I also argue for more inflation in Germany to solve the Eurozone’s problem of distorted relative prices. I would be glad if you could make this response known to your readers.Sincerely yours

Hans-Werner Sinn

Professor of Economics and Public Finance

President of CESifo Group

I was swamped with end of semester duties, and I only managed to read the paper (not the book) this morning. But in spite of Mr Sinn’s polite remarks, I stand by my statement (spoiler alert: the readers will find very little new content here). True, in the paper Mr Sinn advocates some inflation in the core (look at sections 9 an 10). In particular, he argues that

What the Eurozone needs for its internal realignment is a demand-driven boom in the core countries. Such a boom would also increase wages and prices, but it would do so because of demand rather that supply effects. Such demand-driven wage and price increases would come through real and nominal income increases in the core and increasing imports from other countries, and at the same time, they would undermine the competitiveness of exports. Both effects would undoubtedly work to reduce the current account surpluses in the core and the deficits in the south.

This is a diagnosis that we share But the agreement stops around here. Where we disagree is on how to trigger the demand-driven boom. Mr Sinn expects this to happen thanks to market mechanisms, just because of the reversal of capital flows that the crisis triggered. He argues that the capital which foolishly left Germany to be invested in peripheral countries, being repatriated would trigger an investment and property boom in Germany, that would reduce German’s current account surplus. This and this alone would be needed. Not a policy of wage increases, useless, nor a fiscal expansion even more useless.

Problem is, the data speak against Mr Sinn’s belief. Since the crisis hit, capital massively left peripheral countries, and yet this did not fuel domestic demand in Germany. Last August I showed the following figure:

It shows that after a drop (in the acute phase of the financial crisis) due to a sharp decline of GDP, since 2009 domestic demand as a percentage of GDP kept decreasing, in Germany as well as in the rest of the Eurozone. The reversal of capital flows depressed demand in the periphery, but did not boost it in Germany. Mr Sinn is too skilled an economist to fail to see this. The reason is, of course, that the magic investment boom did not happen:

Mr Sinn, being a fine economist, could object that this is because GDP, the denominator, grew more

Mr Sinn, being a fine economist, could object that this is because GDP, the denominator, grew more fell less in Germany than in the rest of the EMU. Well, think again.

Yes, France comes out as investing (privately) less than Germany. But we are far from an investment boom in Germany as well. Mr Sinn, will agree, I ma sure.

Yes, France comes out as investing (privately) less than Germany. But we are far from an investment boom in Germany as well. Mr Sinn, will agree, I ma sure.

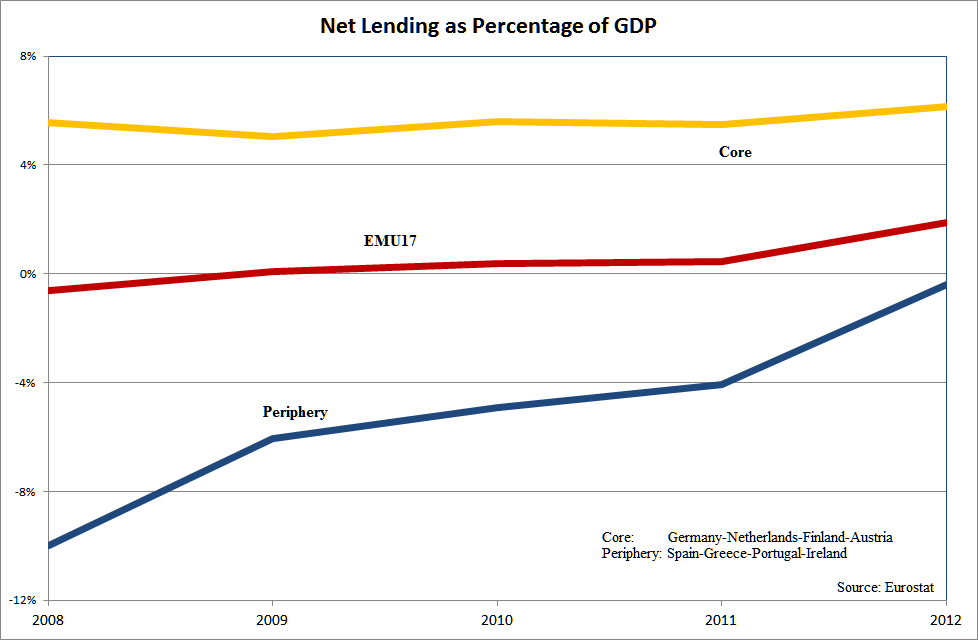

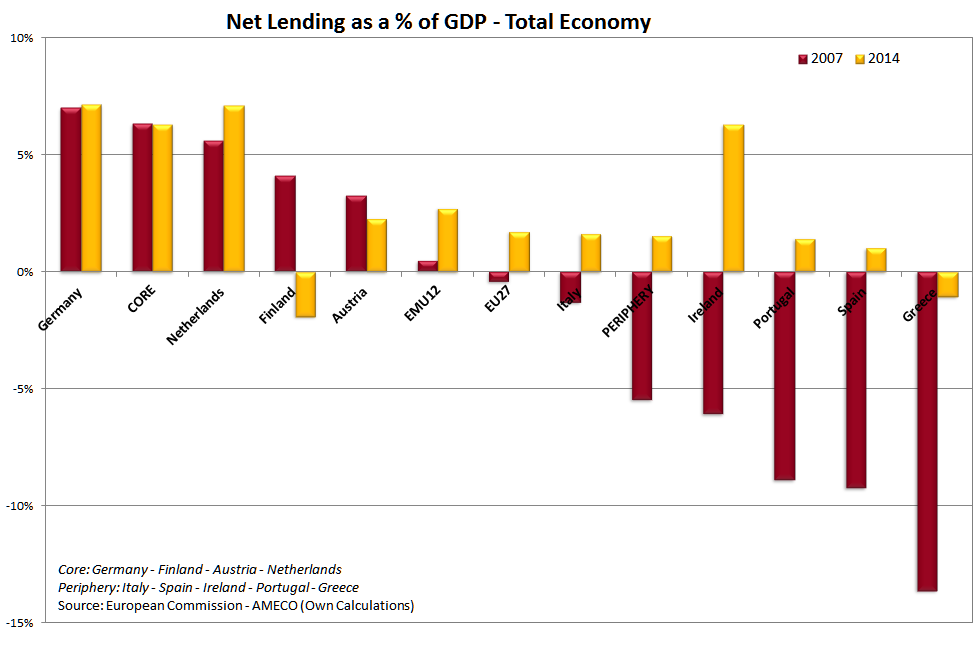

What basically happened, I said it before, is that adjustment was not symmetric. Peripheral countries reduced their excess demand, while Germany and the core did not reduce their excess savings. The result is that, if we compare 2007 to 2014, external imbalances of the periphery were greatly reduced or reversed, while with the exception of Finland the core did not do its homework:

The EMU as a whole became a large Germany, running a current account surplus (it was more or less in balance in 2007), and relying on its exports for growth. A very dubious strategy in the long run.

The EMU as a whole became a large Germany, running a current account surplus (it was more or less in balance in 2007), and relying on its exports for growth. A very dubious strategy in the long run.

The conclusion in my opinion is one and only one: We cannot count on markets alone, in the current macroeconomic situation, if we want rebalancing to take place. In the article he suggested I read, Mr Sinn states that a 4 or 5 per cent inflation rate would be politically impossible to sell to the German public:

Moreover, it is unclear whether the German population would accept being deprived of their savings. Given the devastating experiences Germany made with hyperinflation from 1914 to 1923, which in the end undermined the stability of its society, the resistance against an extended period of inflation in Germany could be as strong or even stronger than the resistance against deflation in southern Europe. After all, a rate of 4.1 per cent for German inflation for 10 years, which would be necessary to allow the necessary realignment between France and Germany without France sliding into a deflation, would mean that the German price level would increase by 50 per cent and that, in terms of domestic goods, German savers would be deprived of 33 per cent of their wealth. If the German inflation rate were even 5.5 per cent, which would be necessary to accommodate the Spanish realignment without price cuts, its price level would increase by 71 per cent over a decade and German savers would be deprived of 42 per cent of their wealth.

This shows all the logic of Ordoliberalism: It is impossible to sell inflation to the the German public, because this would deprive them of their savings. This argument only makes sense if one subscribes to the Berlin View that the bad guys in the south partied with hard earned money of northern (hard) workers. Otherwise the argument makes no sense at all, as high inflation in the core for next few years simply compensates low inflation in the past. Should I remind Mr Sinn that the outlier in terms of labour costs is not the EMU periphery, but Germany?

Also, I find it disturbing that, while acknowledging that inflation in Germany would be needed, Mr Sinn rejects it on the ground that it would be a hard sell. The role of intellectuals and academics is mostly to discuss, find solutions (or at least try), and then argue for them. All the more so if this is unpopular, because it is then that their pedagogical role is most needed. All too often public intellectuals abdicate to their role, and simply follow the trend. Should we all argue in favour of a euro breakup only because public opinion is less and less favorable to the single currency?

Finally, a short comment on another bit of Mr Sinn’s article:

And although the core countries would suffer [from high inflation], the solution would not be comfortable for the devaluating countries either. They will unavoidably face a long-lasting stagnation with rising mass unemployment and increasing hardship for the population at large. People will turn away from the European idea, and voices opting for exiting the euro will gain strength. Thus, it might be politically impossible to induce the necessary differential inflation in the Eurozone.

I don’t really see his point here. But let’s take it for good, just for the sake of argument. I think it is too late to worry about support for the euro in the periphery. It is hard to see how “excessive” inflation in the core would impose more hardness than seven years of adjustment, ill-conceived structural reforms, and self-defeating austerity.

So Mr Sinn, thank you for your mail and for the reference to your paper that I have read with interest. But no, I don’t think I misrepresented you. The core of your argument remains that the burden of adjustment should rest on the periphery’s shoulders. And you failed to convince me that this is right.

Give Me Some Crowding-Out

I just read, a few days late, a very instructive Op-Ed by Otmar Issing for the Financial Times. The zest of the argument is in the first few lines, that are worth quoting:

Imagine you are asked to give advice to a country on its economic policy. The country enjoys near-full employment; its growth is above, or at least at full potential. There is no under-usage of resources – what economists call an output gap – and the government’s budget is balanced, but the debt level is far above target. To top it all monetary policy is extremely loose.

This is exactly the situation in Germany. Recently forecasts for growth have been revised downwards, but so far the overall assessment is unchanged. At present there is no indication of the country heading towards recession. Inflation is low but there is no risk of deflation. From a purely national point of view Germany needs a much less expansionary monetary policy than it is getting from the European Central Bank. This is a strong argument why fiscal policy should not be expansionary, too.

Where is the economic textbook that argues that such a country should run a deficit to stimulate the economy? There is hardly a convincing argument for such advice.

The quote is a perfect example of what is wrong with mainstream thinking in German academic and policy circles. First, the incapacity to fully appreciate to what extent the German national interest is linked to the wider fate of the eurozone. From a purely national point of view, Germany needs stronger growth in the eurozone, its main trading partner. And it needs higher inflation at home and abroad. Which means that no, monetary policy is not too expansionary for Germany, as Issing claims.

But there is a more important issue: Issing seems not to grasp that the problem with the German economy is that it is unbalanced. True, it is near full employment (even if much could be said about the quality of that employment), but it relies too much on exports and too little on domestic demand, with the result that it runs, since 2001, increasing current account deficits. To say it bluntly, Germany has been sitting on the shoulders of the rest of the world economy, and since 2010 it has been followed by the rest of the eurozone that is globally running trade surpluses. I have already said many times that this is a bad (and dangerous) strategy.

I do not know what textbooks Issing reads. Germany’s intellectual tradition must include OrdoTextBooks. The ones I know say that expansionary fiscal policy, at full employment, crowds out private expenditure and exports. And guess what? This is exactly what Germany should do, for its own and its neighbours’ welfare. And if at the same time private expenditure was also boosted, with wage increases (hey, don’t listen to me; listen to the Bundesbank!) and incentives for investment, crowding out could be limited to foreign demand.

So, I read textbooks and I conclude that Otmar Issing is dead wrong. Germany should boldly expand domestic demand (public and private), thus overheating its economy, crowing out exports, and increasing inflation. The effect would be rebalancing of the German economy, growth in the rest of the eurozone, and relief in the rest of the world, for which we would stop being a drag.

Unfortunately this is not bound to happen anytime soon.

Blame the World?

Yesterday’s headlines were all for Germany’s poor performance in the second quarter of 2014 (GDP shrank of 0.2%, worse than expected). That was certainly bad news, even if in my opinion the real bad news are hidden in the latest ECB bulletin, also released yesterday (but this will be the subject of another post).

Not surprisingly, the German slowdown stirred heated discussion. In particular Sigmar Gabriel, Germany’s vice-chancellor, blamed the slowdown on geopolitical risks in eastern Europe and the Near East. Maybe he meant to be reassuring, but in fact his statement should make us all worry even more. Let me quote myself (ach!), from last November:

Even abstracting from the harmful effects of austerity (more here), the German model cannot work for two reasons: The first is the many times recalled fallacy of composition): Not everybody can export at the same time. The second, more political, is that by betting on an export-led growth model Germany and Europe will be forced to rely on somebody else’s growth to ensure their prosperity. It is now U.S. imports; it may be China’s tomorrow, and who know who the day after tomorrow. This is of course a source of economic fragility, but also of irrelevance on the political arena, where influence goes hand in hand with economic power. Choosing the German economic model Europe would condemn itself to a secondary role.

I have emphasized the point I want to stress, once again, here: adopting an export-led model structurally weakens a country, that becomes unable to find, domestically, the resources for sustainable and robust growth. And here we are, the rest of the world sneezes, and Germany catches a cold. The problem is that we are catching it together with Germany:

The ratio of German GDP over domestic demand has been growing steadily since 1999 (only in 19 quarters out of 72, barely a third, domestic demand grew faster than GDP). And what is more bothersome is that since 2010 the same model has been adopted by imposed to the rest of the eurozone. The red line shows the same ratio for the remaining 11 original members of the EMU, that was at around one for most of the period, and turned frankly positive with the crisis and implementation of austerity.It is the Berlin View at work, brilliantly and scaringly exposed by Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann just a couple of days ago. We are therefore increasingly dependent on the rest of the world for our (scarce) growth (the difference between the ratio and 1 is the current account balance).

It is easy today to blame Putin, or China, or tapering, or alien invasions, for our woes. Easy but wrong. Our pain is self-inflicted. Time to change.

Competitive Structural Reforms

Mario Draghi, in an interview to the Journal du Dimanche, offers an interesting snapshot of his mindset. He (correctly in my opinion) dismisses euro exit and competitive devaluations as a viable policy choices:

The populist argument that, by leaving the euro, a national economy will instantly benefit from a competitive devaluation, as it did in the good old days, does not hold water. If everybody tries to devalue their currency, nobody benefits.

But in the same (short) interview, he also argues that

We remain just as determined today to ensure price stability and safeguard the integrity of the euro. But the ECB cannot do it all alone. We will not do governments’ work for them. It is up to them to undertake fundamental reforms, support innovation and manage public spending – in short, to come up with new models for growth. […] Taking the example of German growth, that has not come from the reduction of our interest rates (although that will have helped), but rather from the reforms of previous years.

I find it fascinating: Draghi manages to omit that German increased competitiveness mostly came from wage restraint and domestic demand compression, as showed by a current account that went from a deficit to a large surplus over the past decade. Compression of domestic demand and export-led growth, in the current non-cooperative framework, would mean taking market shares from EMU partners. This is in fact what Germany did so far, and is precisely the same mechanism we saw at work in the 1930s. Wages and prices would today take the place of exchange rates then, but the mechanism, and the likely outcome are the same. Unless…

Draghi probably has in mind a process by which all EMU countries embrace the German export-led model, and export towards the rest of the world. I have already said (here, here, and here) what I think of that. We are not a small open economy. If we depress our economy there is only so much the rest of the world can do to lift it through exports. And it remains that the second largest economy in the world deserves better than being a parasite on the shoulders of others…

As long as German economists are like the guy I met on TV last week, there is little to be optimist about…

Surprise! I (sort of) Agree with Olli Rehn!

Olli Rehn wrote a balanced piece on Germany’s current account surplus. To sum it up:

- He acknowledges that Germany’s surplus is a problem.

- He acknowledges (albeit indirectly) that the initial source of the problem were capital flows from Germany and the core to the periphery; flows that did not go into productive investment but fueled bubbles.

- He (correctly) argues that over the long run some excess savings from Germany is justified by the need to provide for an ageing population.

- He points out that investment has been too low and needs to increase (possible within the framework of an energy transition).

- He also mentions, without mentioning it, the problem of excessively low wages and pauperisation of the labour force, calling for increases in wages and reduction in taxes to boost domestic demand.

This seems to me a reasonable analysis, and I would welcome an official position of the Commission along these lines. Yet, I think that what is missing in Rehn’s piece, and in most of the current debate, is a clear articulation of between the long and the short run.

I would not object on the need for Germany to run modes surpluses on average over the next years, to pay for future pensions and welfare. It is after all a mature and ageing country. Even more, I would agree with the argument that low wages need to increase, and that bottlenecks that prevent domestic demand expansion should be removed. In other words, I would most likely agree on the Commission’s prescriptions for the medium-to-long run.

Nevertheless, there is a huge hole in Olli Rehn’s analysis, that worries me a bit. Rehn seems to overlook the need to do something here and now. Today, with the periphery of the eurozone stuck in recession, emerging economies sputtering, and continuing jobless growth in the US, the world desperately needs a boost from countries that can afford it. And unfortunately there are not many of these.

Germany is instead siphoning off global demand, making the rest of the world carry its economy when it should do the opposite. As a quick reversal of private demand is unlikely, (this, I repeat should be a medium run target), I see no other option in hte very short run than a substantial fiscal expansion.

A cooperative Germany should implement short run expansionary policies (the need for public investment is undeniable), while working to rebalance consumption, investment and savings in the medium run, with the objective of a small current account surplus in the medium run.

That, incidentally, would not make them Good Samaritans. Ending this endless recession in the eurozone (yes I know, it is technically over; but how happy can we be with growth rates in the zero-point range?) is in the best interest of Germany as much as of the rest of the eurozone (and of the world).

A clear articulation between the different priorities in the short and in the medium-long run would benefit the debate. The problem is that then Olli Rehn should acknowledge that in the short run there is no alternative to expansionary fiscal policies in the eurozone core. That would be asking too much…

Incomprehensible? Really?

Germany rejected the US Treasury’s criticism of the country’s export-focused economic policies as “incomprehensible”. Much has been said about that. Let me just add some pieces of evidence, just to gather them all in the same place.

Exhibit #1: Net Lending Evolution

Note#1 : I took net lending because because net income flows from residents to non residents (not captured by the current account) may be an important part of a country’s net position (most notably in Ireland). Note #2: I took away France and Italy from the two groups called “Core” and “Periphery”, because their net position was relatively small as percentage of GDP in 2008, and changed relatively little.

Read More

Lilliput in Deutschland

Following the widely discussed U.S. Treasury report on foreign economic and currency policies, that for the first time blames Germany explicitly for its record trade surpluses, I published an op-ed on the Italian daily Il Sole 24 Ore (in Italian), comparing Germany with China. My argument there is the following:

- Before the crisis the excess savings of China and Germany, the two largest world exporters, contributed to the growing global imbalances by absorbing the excess demand of the U.S. and of other economies (e.g., the Eurozone periphery) that made the world economy fragile. (more here)

- In the past decade, China seems to have grasped the problems yielded by an export-led growth model, and tried to rebalance away from exports (and lately investment) towards consumption (more here). The adjustment is slow, sometimes incoherent, but it is happening.

- Germany walked a different path, proudly claiming that the compression of domestic demand and increased exports were the correct way out of the crisis (as well as the correct model for long-term growth)

- Germany’s economic size, its position of creditor, and its relatively better performance following the sovereign debt crisis, (together with a certain ideological complicity from EC institutions) allowed Germany to impose the model based on austerity and deflation to peripheral eurozone countries in crisis.

- Even abstracting from the harmful effects of austerity (more here), I then pointed out that the German model cannot work for two reasons: The first is the many times recalled fallacy of composition): Not everybody can export at the same time. The second, more political, is that by betting on an export-led growth model Germany and Europe will be forced to rely on somebody else’s growth to ensure their prosperity. It is now U.S. imports; it may be China’s tomorrow, and who know who the day after tomorrow. This is of course a source of economic fragility, but also of irrelevance on the political arena, where influence goes hand in hand with economic power. Choosing the German economic model Europe would condemn itself to a secondary role.

I would add that the generalization of the German model to the whole eurozone is leading to increasing current account surpluses. Therefore, this is not simply a European problem anymore. By running excess savings as a whole, we are collectively refusing to chip in the ongoing fragile recovery. The rest of the world is right to be annoyed at Germany’s surpluses. We continue to behave like Lilliput, refusing to play our role of large economy.

Let me conclude by noticing that today in his blog Krugman shows that sometimes a chart is worth a thousand (actually 748) words: