Archive

To Reshore, or not to Reshore, that is the question

[Note: this is a slightly edited ChatGPT translation of an article for the Italian daily Domani]

In June 2023, over three years after the beginning of the pandemic, the Global Container Freight Index, one of the measures of maritime transportation cost, has returned to 2019 levels. At its peak in the summer of 2021, it had nearly increased tenfold. The Global Supply Chain Pressure Index (GSCPI) calculated by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York has also been below historical averages for a few months now. These developments, along with the decline in energy prices (though still with significant variability), indicate that we can now consider the phase of disruption in global production and trade, which began with the pandemic and continued in 2021 and 2022 when the economy restarted, to be closed.

However, having returned (more or less) to normalcy doesn’t mean that we should stop questioning the vulnerabilities highlighted by the crisis. Since 2020, an interesting debate has been ongoing about the strategic autonomy of major economies (such as the European one) that have discovered to be dependent on not always reliable foreign suppliers, and more generally on the complexity and fragility of the globalized economy. This is a complex discourse, where considerations on value chains intertwine with the broader discussion on the costs and benefits of globalization. It’s not surprising, therefore, that reaching clear-cut conclusions is challenging.

Cost minimization cannot be the only guide

Advocates of reshoring, the bringing back some of the production processes previously outsourced to extreme levels, put forth several arguments:

The first is that the outsourcing of production processes has gradually eroded the strategic autonomy of many advanced countries, resulting in detrimental outcomes not only economically but also geopolitically. The struggle for dominance between emerging and advanced economies, along with the risks to public health posed by climate change, make it essential to seriously consider building rapid response capabilities to energy, health, or geopolitical shocks without depending on imports.

Then, the experience of recent years also shows that excessively long value chains indeed minimize costs, but at the cost of great fragility. Consider that in the first quarter of 2020, when only China had gone into lockdown (Italy being the first European country to do so, only shut down its economy on March 9), GDP plummeted nearly everywhere due to difficulties in sourcing for businesses and wholesalers (-6.4% for Italy, -4.7% for Spain, -5.2% for France, -1.2% for Germany, -2.8% for the Eurozone; OECD data). According to reshoring proponents, the almost exclusive emphasis on minimizing production costs could have been justified in a macroeconomic and geopolitical stable context (or at least one that seemed stable) like the one we lived in until the early 2000s. If the world in the coming years will resemble the turbulent one of recent times, it might be worthwhile for countries and businesses to attempt to protect themselves by shortening value chains, even if it leads to higher production costs. It’s interesting to note that this discussion is another manifestation of the crisis of the Consensus that dominated macroeconomics until the early 2000s: It’s evident that if one believes in the market’s capacity to absorb shocks without external aid, neglecting “resilience” to solely focus on production costs is the winning strategy. When faith in the market as the sole necessary institution for optimal allocations of resources wanes, other considerations must necessarily come into play.

The third reason for shortening value chains is tied to the urgency of the energy transition. With plummeting transportation costs, scattering the production process by locating each phase where it was most convenient allowed for cost minimization. But if environmental costs were considered, the calculation might have been different. Whether due to social pressure, to public action (through regulation or taxation), or simply to the awareness of imminent catastrophe, businesses will inevitably be driven to internalize part of the environmental costs of excessively long value chains. Repatriating some of the production processes, once environmental costs are properly considered, in the future might be the optimal choice.

Advocates of rethinking our production methods, in short, emphasize the necessity of not limiting oneself to the short-sighted maximization of monetary profits, but rather adopting a long-term perspective where resilience (including geopolitical) and social and environmental sustainability are appropriately considered.

Not throwing out the baby of globalization with the bathwater of excessively fragile value chains

While there is almost unanimity on the need to regain strategic autonomy for essential goods related to public health and national security, the voices against extensive reshoring for non-strategic goods are predominant. In recent decades, global value chains have been one of the pillars of trade expansion and economic growth in emerging and developing countries. A recent World Bank report estimates that, in the next ten years, reshoring by high-income countries and China would push 52 million people below the poverty line (especially in sub-Saharan Africa). The International Monetary Fund, in the April 2022 edition of the World Economic Outlook, after confirming that during the pandemic value chains contributed to exporting the economic crisis, notes that these negative spillover effects have decreased in intensity in the subsequent waves of the pandemic. This seems to indicate that value chains were more adaptable than initially believed.

In essence, those opposing a radical shortening of value chains recommend not throwing away the benefits of globalization due to excessively fragile value chains. Businesses should instead increase resilience through diversification of sourcing, better inventory management, and so on. It’s interesting to note that for decades it was advanced countries that pushed for globalization, while developing countries were vainly seeking protection due to the very well justified fear of being overwhelmed. Today, the opposite is happening: the debate on reshoring mainly occurs in advanced countries, while emerging countries strongly defend the global trade system.

Predicting what will happen in the coming years is difficult. What is certain, whether reshoring becomes significant or remains marginal, but businesses organize themselves to better absorb potential shocks, production processes will no longer be solely oriented towards cost minimization, and average costs will therefore increase. Higher production costs will necessarily impact prices and inflation.

This text is excerpted from a section of Oltre le banche centrali, available on August 25th from Luiss University Press.

There is no Trade-off. Saving Lives is Good for the Economy

At the beginning of the COVID pandemic, when policy makers were struggling to find ways to cope with a crisis that most of them had under estimated, the public discourse was dominated by a trade-off: should we shut down economic activity to enforce/facilitate social distancing and curb the pandemic curve before it leads to the collapse of health care systems, and to deaths by the hundreds of thousands? Or should we just let the death toll be what it has to be, and let the virus pass through our countries (build “herd immunity”), avoiding severe economic consequences? To put it somewhat brutally, should we save lives or the economy? This trade-off certainly is in the minds of most governments, even if most of them carefully avoided letting it surface in their public discourse. The countries that stopped the economy justified it as the price to pay “to save lives”; just a handful of governments made it explicit that they had made the opposite choice. The most reckless undoubtedly was Boris Johnson who initially argued that the best strategy was to build herd immunity by letting the virus reach 4O millions people, whatever the cost in human lives would be. Trump and Bolsonaro (a merry fellowship indeed) had a very similar stance, minimising the cost at first, and then arguing that the economy should not be stopped. But many other countries in Europe, with the same trade-off in mind, delayed going into lockdown in spite of Italy spiraling into the crisis just around the corner. They simply were less impudent than the British PM, while considering the same strategy.

It is reassuring that for most countries reality (and opinion polls) caught up, so that strategies eventually converged to giving priority to the health crisis over the economy: more or less compulsory social distancing, and the freeze of economic activity are now generalized, with almost half of the world population under lockdown.

This is reassuring not only because priority should be given to saving human lives. But also because, as I have always believed, the trade-off between public health and the economy is complete nonsense. I was glad to read a piece by Luigi Guiso and Daniele Terlizzese (in Italian) making this point. I just wish that they (or somebody else, including myself) had made it before. This would have been an immensely more valuable contribution by economists, than playing epidemiologists and fitting exponential curves on social networks (I never did!).

But why is the trade-off nonsense? Simply put, because the pandemic will cause enormous harm to the economy, whether it claims lives by the millions or not. Suppose the BoJo initial strategy was implemented, and a few dozens millions of British people were infected, many of them for several weeks. Abstracting from fatality rates, labour supply would drop for months, and disruption in production would follow. Fear of contagion would limit social interaction (a sort of self-imposed confinement) for many, impacting consumption, investment, but also productivity. Some sectors (travel, tourism, services) would see significant drops in activity. The global value chains would be disrupted, and trade would take a hit. Furthermore, the collapse or near-collapse of health care systems would impact the quality of life (and sometimes cause the death) not only of those affected by the virus, but also of the many that in normal times need to resort to health care services. Consumer confidence and corporate sentiments would remain low for months, consumption and investment would stagnate, government intervention would be needed as much as it is needed in the lockdown. Last, but not least, the heavy toll paid to the pandemic crisis would impact human capital (think of casualties among doctors), and thus productivity and growth in the long run.

A slowdown would therefore be inevitable, a harsh one actually. But still, it could be argued that such a scenario would not be worse than the total halt we are experiencing. I beg to disagree. Let me go back to Mario Draghi’s piece in the Financial Times. The former ECB boss there argues that the urgent task of policy makers is to keep the businesses that are short of liquidity afloat whatever it takes, so that when the rebound will happen, the productive capacity will be able to provide goods and services, and incomes will recover quickly. Said it differently, if policy makers manage to minimize permanent damage to the supply side of the economy, a short lived shock, however brutal, might leave few scars.

But there is more than that. In fact, the minimization of permanent damage becomes harder and harder, and probably costlier and costlier, the longer the crisis is. Following the crisis of 2008-2010, an interesting literature developed on the permanent effects of crises. This literature highlights how long and low-intensity slumps have an impact through hysteresis on the capital (human and physical) of the economy and permanently lower the potential growth of the economy. The conclusion to be drawn from this literature is that the risk of letting the economy in a slump for too long, and hence suffer permanent damage, is larger than the risk of over reacting in the short-run.

Applying this mindset to the current pandemic dispels once and for all the trade-off; more than that. It allows to rank the two policy options. Doing whatever it takes to save lives is causing a deep and hopefully short-lived economic slump. However devastating for the economy, such a slump is much easier to manage for policy makers than the (maybe) marginally milder recession but spread over a longer period of time, that one would have by not imposing a total lockdown of the economy. Shutting down the economy saves lives, AND it is better for the economy. A no brainer, in fact.

Even the most cynical among our leaders should understand this: Saving as many lives as possible is the best we can do to save the economy and their chances of reelection.

My Two Cents on the “Yellow Vests” Movement

In a widely commented televised address President Macron has made a last-minute attempt to stop the “yellow vests” wave, that is investing France and his presidency. After a dramatic (a bit too much to seem sincere, if you ask me) mea culpa on past arrogance, and a promise to “listen to the suffering of the people”, Macron announced a few changes to the French budget law, to sustain the purchasing power of the lower part of the income distribution. The most important and immediate changes are: an increase of minimum wage (more precisely of the “employment subsidy” that is given to most people working at or around minimum wage): the exemption from taxes and social contribution of extra hours (a very popular measure that had been introduced by Nicolas Sarkozy and later abolished by François Hollande); and last but not least, the repeal of the increase of social contributions for retirees, and the confirmation of the freezing (for at least the year 2019) of the “ecological tax” on fuel. Macron also signaled the intention to backtrack on his vertical leadership style (the président jupitérien); he pleaded for renewed role for intermediate bodies (most notably the mayors and local politicians) in putting in place a concerted effort (a “social compact”) to boost growth and social cohesion.

Will Macron’s announcement appease the uprising that inflames France? Most probably not, because they suffer from an original sin, a contradiction that the President is unwilling (or incapable) of seeing. The yellow vest protest originates from the gas price increase, that affected rural households and farmers in particular? But the malaise has much deeper roots, that are widespread. The French economy feels, after ten years, the full weight of a crisis that has hit very hard the middle and lower classes: Unemployment that fell too slowly (costing re-election to François Hollande ; austerity that, although less marked than in the peripheral eurozone countries, has reduced the perimeter and coverage of public services and of the welfare system, while increasing the tax burden; and, finally, the reduction of family allocations and welfare in general, which particularly affected the most disadvantaged categories. All of this led to what Julia Cagé, on French daily Le Monde, called “the purchasing power crisis”, that simmered for a long time, before exploding in the past weeks.

Emmanuel Macron has an enormous responsibility for the bursting of the crisis. True, the increase in the tax burden for the middle class is mainly due to François Hollande (under the impulse of an ambitious undersecretary, and then minister of the economy, named … Emmanuel Macron). One might even argue that the budget law for 2019 reverses the trend as that the reduction of some taxes (in particular the elimination of the housing tax for the majority of households, and the flat tax on capital income) has more than offset the reduction in social benefits.

What explains then the fact that the discontent emerges, so violently, just now? The explanation is simple: it is to be found in the approach that the French President pursued since he beginning of his mandate. Like Donald Trump, with whom he disagrees on almost everything, Emmanuel Macron believes in the so-called “trickle down” theory: shifting the tax burden away from the rich is the best strategy to revive growth, because these people are more productive than the average, and invest the extra income in innovative activities. The fruits of higher growth would then percolate to everyone, even those who were initially penalized by the tax reform. From the beginning of his mandate, Macron’s choice to give France a pro-business image was clear, leading to a drastic reduction of taxes on the richest, and making the taxation, for the upper part of the distribution, fundamentally regressive.

The last budget law represents the clearest proof of this approach. The “Institute for Public Policies” has shown (see the figure, taken from a Le Monde article appeared last October) that while the overall disposable income slightly increases, the bottom 20% and the upper-middle class see a substantial worsening of their situation, while the very rich (the top 1%) see their purchasing power increase of 6%.

The problem is, as an increasing body of evidence shows, that trickle down does not work. Favoring the richest does not increase productive investment (it rather tends to boost non-produced asset prices and unproductive consumption), and the impact on growth is both negligible and not shared; these days’ demonstrations stand to prove it. History cannot be rewritten, but the attempt to twist the tax system in favor of the ecological transition would probably have been met with much more enthusiasm, in a country like France where environmental awareness is high, where it not accompanied by the sentiment of increasing social injustice that Macron’s economic policies have deepened.

It is interesting to notice, in this regard, that traditional media have given a somewhat distorted image of the protest movement (which is very hard to clearly decrypt). A group of researchers from Toulouse University uses lexicographic analysis to show that the narrative of traditional media was centered on revolt against taxes (ras-le-bol fiscal), and therefore in contradiction with the request of better public services; this does not correspond to the message coming from social networks that organized “from the bottom” the movement, in which instead the predominant mood was revolt against social injustice and against the elites that grow richer and richer, while leaving the check for the others to pay. To sum up, a plea for a more equal and cohesive society.

How will this end? It is hard to say. The yellow vests have obtained a partial win, with the freezing of the gas increase, and with the measures announced by Macron on Monday. But it is unlikely that we will see a substantive change of economic policy, precisely because of the President’s views outlined above. He rushed to rule out any reinstatement of the wealth tax, because “in the past unemployment increased even when the wealth tax existed” (a rather unconvincing argument, to say the truth).

If higher incomes are not called to contribute to the effort (towards ecological transition, but more generally towards the financing of the French social model), even the measures just announced will have a very limited impact. The State will somehow have to take back with one hand (for example by reducing public services, that benefit lower income most, or increasing other taxes) what it just handed out with the other hand. The demand for social justice that confusedly emerges from the yellow vests movement will once more go unanswered, leaving untouched the tension that is ripping the French (and not just the French) society.

To meet these needs, a new political proposal would have to put the complex theme of the redistribution of resources in a globalized world at the center of its project. It would be necessary to rediscover the “Regulatory State” which, in the golden years of social democracy (and of the social right), guaranteed social and macroeconomic stability, and thus laid the foundations for investment, innovation, and growth. That role is more difficult to define in a globalized world in which individual States have limited room for maneuver, and in which therefore international cooperation, however difficult, is now the only way forward. But this challenge can not be avoided if we do not want movements such as those of yellow vests to fall prey to nativist autocratic populism.

(This is the translation of a piece I published in Italian on the Luiss Open website)

A Piketty Moment

Update (10/27): Comments rightly pointed to different deflators for the two series. I added a figure to account for this (thanks!)

Via Mark Thoma I read an interesting Atalanta Fed Comment about their wage tracker, asking whether the recent pickup of wages in the US is robust or not.

The first thing that came to my mind is that we’d need a robust and sustained increase, in order to make up for lost ground, so I looked for longer time series in Fred, and here is what I got

This yet another (and hardly original) proof of the regime change that occurred in the 1970s, well documented by Piketty. Before then, US productivity (output per hour) and compensation per hour roughly grew together. Since the 1970s, the picture is brutally different, and widely discussed by people who are orders of magnitude more competent than me.

[Part added 10/27: Following comments to the original post, I added real compensation defled with the GDP deflator. While this does not account for purchasing power changes, it is more directly comparable with real output. Here is the result:

The commentators were right, the divergence starts somewhat later, in the early 1980s. This makes it less of a Piketty moment, while leaving the broad picture unchanged.]

Next, I tried to ask whether it is better for wage earners, in this generally gloomy picture, to be in a recession or in a boom. I computed the difference between productivity (output per hour) and wages (compensation per hour), and averaged it for NBER recession and expansion periods (subperiods are totally arbitrary. i wanted the last boom and bust to be in a single row). Here is the table:

| Yearly Average Difference Between Changes in Productivity and in Wages | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Recessions | In Expansions | Overall | % of Quarters in Recession | |

| 1947-2016 | 1.51% | 0.40% | 0.57% | 15% |

| 1947-1970 | 1.62% | -0.14% | 0.19% | 19% |

| 1970-2016 | 1.42% | 0.67% | 0.76% | 13% |

| 1980-1992 | 0.64% | 0.84% | 0.81% | 17% |

| 1993-2000 | N/A | 0.68% | 0.68% | 0% |

| 2001-2008Q1 | 4.07% | 1.10% | 1.41% | 10% |

| 2008Q2-2016Q2 | 2.17% | 0.12% | 0.49% | 18% |

| Source: Fred (my calculations) | ||||

| Compensation: Nonfarm Business Sector, Real Compensation Per Hour | ||||

| Productivity: Nonfarm Business Sector, Real Output Per Hour | ||||

No surprise, once again, and nothing that was not said before. The economy grows, wage earners gain less than others; the economy slumps, wage earners lose more than others. As I said a while ago, regardless of the weather stones keep raining. And it rained particularly hard in the 2000s. No surprise that inequality became an issue at the outset of the crisis…

There is nevertheless a difference between recessions and expansions, as the spread with productivity growth seems larger in the former. So in some sense, the tide lifts all boats. It is just that some are lifted more than others.

Ah, of course Real Compensation Per Hour embeds all wages, including bonuses and stuff. Here is a comparison between median wage,compensation per hour, and productivity, going as far back as data allow.

I don’t think this needs any comment.

Convergence, Where Art Thou?

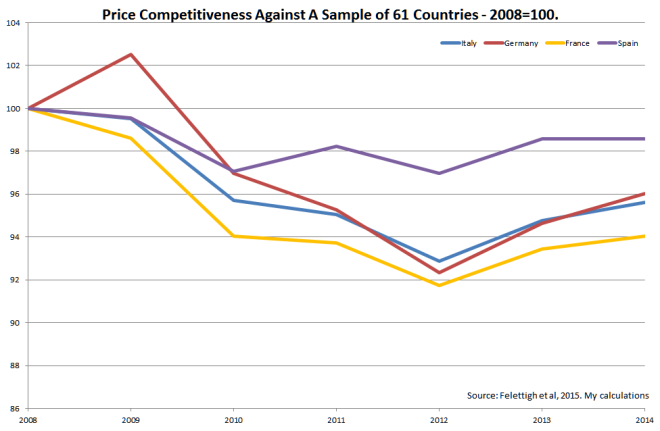

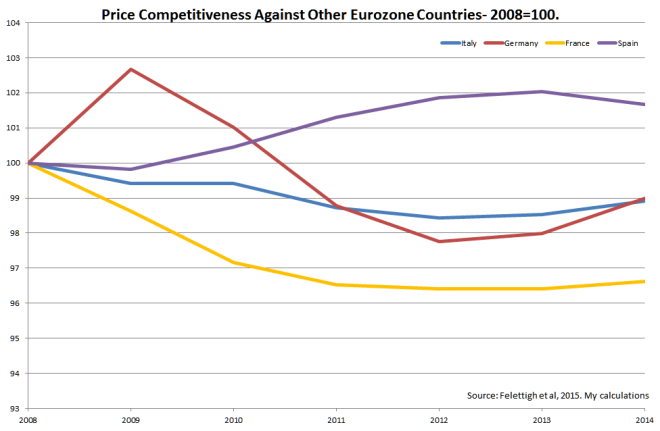

A new Occasional Paper details the new methodology adopted by the Bank of Italy for calculating an index of price competitiveness, and applies it to the four largest eurozone economies.

I took the time to copy the numbers of table 3 in an excel file (let’s hope for the best), and to look at what happened since 2009. Here is the evolution of price competitiveness (a decrease means improved competitiveness):

I find this intriguing. We have been sold the story of Spain as the success story for EMU austerity as, contrary to other countries, it restored its external balance through internal devaluation. Well, apparently not. Since 2008 its price competitiveness improved, but less so than in the three other major EMU countries.

The reason must be that the rebalancing was internal to the eurozone, so that the figure does not in fact go against austerity nor internal devaluation. For sure, within eurozone price competitiveness improved for Spain. Well, think again…

This is indeed puzzling, and goes against anedoctical evidence. We’ll have to wait for the new methodology to be scrutinized by other researchers before making too much of this. But as it stands, it tells a different story from what we read all over the places. Spain’s current account improvement can hardly be related to an improvement in its price competitiveness. Likewise, by looking at France’s evolution, it is hard to argue that its current account problems are determined by price dynamics.

Without wanting to draw too much from a couple of time series, I would say that reforms in crisis countries should focus on boosting non-price competitiveness, rather than on reducing costs (in particular labour costs). And the thing is, some of these reforms may actually need increased public spending, for example in infrastructures, or in enhancing public administration’s efficiency. To accompany these reforms there is more to macroeconomic policy than just reducing taxes and at the same time cutting expenditure.

Since 2010 it ha been taken for granted that reforms and austerity should go hand in hand. This is one of the reasons for the policy disaster we lived. We really need to better understand the relationship between supply side policies and macroeconomic management. I see little or no debate on this, and I find it worrisome.

Reform or Perish

Very busy period. Plus, it is kind of tiresome to comment daily ups and downs of the negotiation between Greece and the Troika Institutions.

But as yesterday we made another step towards Grexit, it struck me how close the two sides are on the most controversial issue, primary surplus. Greece conceded to the creditors’ demand of a 1% surplus in 2015, and there still is a difference on the target for 2016, of about 0.5% (around 900 millions). Just look at how often most countries, not just Greece, respected their targets in the past, and you’ll understand how this does not look like a difference impossible to bridge.

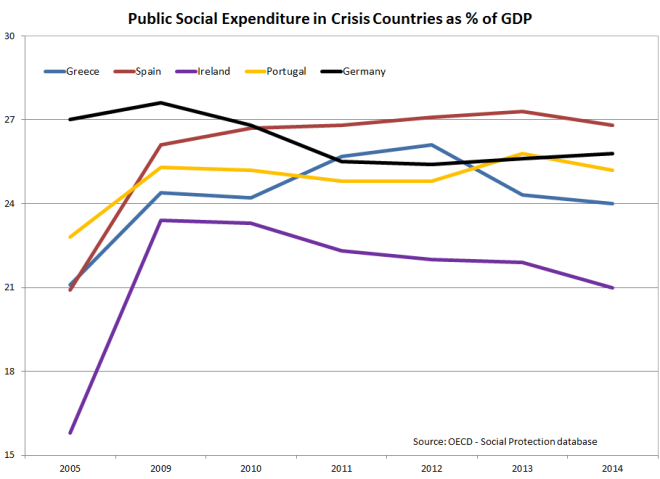

The remaining issue is reforms. Creditors argue that Greece cannot be trusted in its commitment to reform. After all, they cheated so often in the past… In particular, creditors point at one of Syriza’s red lines, the refusal to touch pension reforms, as proof that the country is structurally incapable of reform. And here is the proof, the percentage of GDP that crisis countries spent in welfare::

I took total social expenditure that bundles together pensions, expenditure for supporting families, labour market policies, and so on and so forth. All these expenditure that, according to the Berlin View, choke the animal spirits of the economy, and kill productivity.

Well, Greece does not do much worse than its fellow crisis economies, but it is true that it is hard to detect a downward trend. The reform effort was not very strong, and certaiinly not adapted to an economy undergoing such a terrible crisis. The very fact that after four years of adjustment program the country spends 24% of its GDP in social protection, is a proof that it cannot be trusted.This is just proof that, once more, the Greek made fun of their fellow Europeans, and that they want us to pay for their pensions.

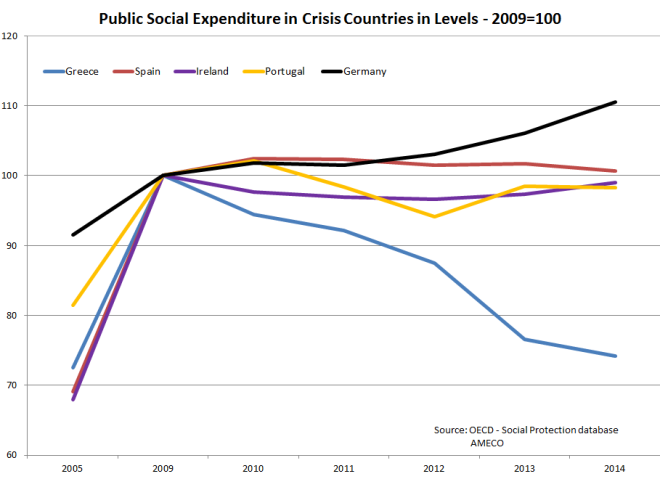

Hold on. Did I just say “terrible crisis”? What was that story of ratios, denominators and numerators? The ratio is today at the same level as 2009. But what about actual expenditure? There is a vary simple way to check for this. Multiply each of the lines above for the value of GDP. Here is what you get (normalized at 2009=100, as country sizes are too different):

The picture looks quite different, does it? Greece, whose crisis was significantly worse than for the other countries, slashed social expenditure by 25% in 5 years (I know, I know, it is current expenditure. I am too busy to deflate the figure. But I challenge you to prove that things would be substantially different). Now, just in case you had not noticed, social expenditure has an important role as an automatic stabilizer: It supports incomes, thus making hardship more bearable, and lying the foundations for the recovery. In a crisis the line should go up, not down. This picture is yet another illustration of the Greek tragedy, and of the stupidity of the policies that the Troika insists on imposing. By the way, notice how expenditure increased from 2005 to 2009, in response to the global financial crisis. A further proof that sensible policies were implemented in the early phase of the crisis, and that we went berserk only in the second phase.

Ah, and of course virtuous Germany, the model we should all follow, is the black line. Do what I say…

One may object that focusing on expenditure is misleading. There is more than expenditure in assessing the burden of the welfare state on the economy. While Greece slashed spending, its welfare state did not become any better; its capacity to collect taxes did not improve, that its inefficient public administration and its crony capitalism are stronger than ever. Yes, somebody may object all that. That someone is Yanis Varoufakis, who is demanding precisely this: stop asking that Greece slashes spending, and lift the financial constraint that prevents any meaningful medium term reform effort. Reform is not just cutting expenditure. Reform is reorganization of the administrative machine, elimination of wasteful programs, redesigning of incentives. All that is a billion times harder to do for a government that spends all its energies finding money to pay its debt.

Real reform is a medium term objective that needs time, and sometimes resources. In a sentence, reform should stop being associated with austerity.

But hey, I am no finance minister. Just sayin’…

The IMF: Of Words and Actions

Some comments, and endless twitter discussions on my Blanchard Touch post call for a couple of clarifications.

The first has to do to the most common reaction, that has been: “the IMF may well have made advances in its analysis, but the policy prescriptions are remarkably unchanged. So what good is it?” After all, isn’t the IMF considered an hardliner in the current Troika Institutions‘ negotiation with Greece? No Blanchard touch, there.

These objections are of course justified, but in my opinion they miss an important point: Blanchard is not the IMF executive director. Nor the representative of a major country. He is “only” the head of the research department, and as such his job is to provide analyses, not to decide the use of these analyses made by a process that (luckily) is political in nature. Does this mean that what Blanchard and his staff do is irrelevant? Of course not. I do think that making the debate evolve is a fundamental task for public figures like Blanchard. One of the strength of the Washington Consensus has been the narrative that accompanied it, the market efficiency hypothesis that laid the theoretical foundations of supply side policies. This is why I believe that the fact that the narrative is crumbling, among other things thanks to the IMF own research, is of paramount importance. The change in narrative is a precondition for a policy change. The hiatus between the Fund’s actions and words will be increasingly visible, and eventually, I hope, it will lead to a change of policies. I cannot believe that the narrative is irrelevant; otherwise I would have chosen a different job.

The second clarification concerns the end of my post:

If I write a paper saying that austerity will not be costly because multipliers are 0.5, and 2 years later retract my previous statement and argue that austerity is in fact self defeating, the impact on the world is zero. If the IMF does the same, during the two years huge suffering will be needlessly inflicted to masses of people. This poses a problem, as research by definition may be falsified. In the past an institution like the IMF would never have admitted a mistake. And we certainly do not want to go back there. Today they do admit the mistakes, but the suffering remains. The only way out to this problem is that the “new” IMF should learn to be cautious in its policy prescriptions, and always remember that any policy recommendation is bound to be sooner or later proven inappropriate by new data and research. We don’t live in a black and white world. Adopting a more prudent stance in dictating policies would be wise (in Brussels as well, it goes without saying)

By this I surely did not mean that the IMF should refrain from giving policy advice. Nor that governments should follow their guts instead of informed analysis, as one reader very clearly put it. I meant that the first and most important achievement for a policy adviser is to abandon dogmatism, and acknowledge that however robust we believe our knowledge to be, there always is a chance that it will be proved wrong. With such an attitude, policy advice would become “cautious” in the sense of being aware of possible unintended consequences of policies; policies that should therefore be implemented with in mind alternative scenarios. Just to make an example, the IMF could have suggested, as it did, to implement austerity based on the belief that the multiplier was low. But it should have asked governments to do it gradually, in order to be ready to reverse course in case the estimated multipliers would prove (as it did) to be larger. In a sentence, being cautious means avoiding advising for extreme behaviors that could prove to be extremely costly and hard to unwind. Especially in crisis situations, policy makers should look east and cross the river by feeling the stones.

I would also like to add that in the case of the Washington Consensus, we had already, in the past decade, a number of episodes when its prescriptions turned out to be catastrophic. Thus, caution would have been even wiser. But hey, dogmatism is by definition unwise…

The Blanchard Touch

Yesterday I commented on the intriguing box in which the IMF staff challenges one of the tenets of the Washington consensus, the link between labour market reform and economic performance.

But the IMF is not new to these reassessments. In fact over the past three years research coming from the fund has increasingly challenged the orthodoxy that still shapes European policy making:

- First, there was the widely discussed mea culpa in the October 2012 World Economic Outlook, when the IMF staff basically disavowed their own previous estimates of the size of multipliers, and in doing so they certified that austerity could not, and would not work (of course this led EU leaders to immediately rush to do more of the same).

- Then, the Fund tackled the issue of income inequality, and broke another taboo, i.e. the dichotomy between fairness and efficiency. Turns out that unequal societies tend to perform less well, and IMF staff research reached the same conclusion. And once the gates opened, it did not stop. The paper by Berg and Ostry was widely read. Then we had Ball et al on the distributional effects of fiscal consolidation (surprise, it increases inequality). Another paper investigated the channels for this link, highlighting how consolidation leads to increased inequality mostly via unemployment. And just last week I assisted to a presentation by IMF economists showing how austerity and inequality are positively related with political instability.

- On labour markets, before yesterday’s box 3.5, the Fund had disseminated research linking increased inequality with the decline in unionization.

- Then, of course, the “public Investment is a free lunch” chapter three of the World Economic Outlook, in the fall 2014.

- In between, they demolished another building block of the Washington Consensus: free capital movements may sometimes be destabilizing…

These results are not surprising per se. All of these issues are highly controversial, so it is obvious that research does not find unequivocal support for a particular view. All the more so if that view, like the Washington Consensus, is pretty much an ideological construction. Yet, the fact that research coming from the center of the empire acknowledges that the world is complex, and interactions among agents goes well beyond the working of efficient markets, is in my opinion quite something.

What does this mass (yes, now it can be called a mass) of work tells us? Three things, I would say. First, fiscal policy is back. it really is. The Washington Consensus does not exist anymore, at least in Washington. Be it because the multipliers are large, or because it has an impact on income distribution (and on economic efficiency); or again because public investment boosts growth, fiscal policy has a role to play both in dampening business cycle fluctuations and in facilitating stable and balanced long term growth. The fact that a large institution like the IMF has lent its support to this revival of consideration for fiscal policy, makes me hope that discussions about macroeconomic policy will be less ideological, even once the crisis will have passed.

The second thing I learn is that the IMF research department proves to be populated of true researchers, who continuously challenge and test their own views, and are not afraid of u-turns if their own research dictates them. I am sure it has always been the case. What is different from the past is that now they have a chief economist who seems more interested in understanding where the world goes than in preaching a doctrine.

The third remark is more problematic. If I write a paper saying that austerity will not be costly because multipliers are 0.5, and 2 years later retract my previous statement and argue that austerity is in fact self defeating, the impact on the world is zero. If the IMF does the same, during the two years huge suffering will be needlessly inflicted to masses of people. This poses a problem, as research by definition may be falsified. In the past an institution like the IMF would never have admitted a mistake. And we certainly do not want to go back there. Today they do admit the mistakes, but the suffering remains. The only way out to this problem is that the “new” IMF should learn to be cautious in its policy prescriptions, and always remember that any policy recommendation is bound to be sooner or later proven inappropriate by new data and research. We don’t live in a black and white world. Adopting a more prudent stance in dictating policies would be wise (in Brussels as well, it goes without saying). And of course, the disconnect between the army and the general is also a problem.

What Structural Reforms?

I am ready to bet that the latest IMF World Economic Outlook, that was presented today in Washington, will make a certain buzz for a box. It is box 3.5, at page 36 of chapter 3, which has been available on the website for a few days now. In that box, the IMF staff presents lack of evidence on the relationship between structural reforms and total factor productivity, the proxy for long term growth and competitiveness. (Interestingly enough people at the IMF tend to put their most controversial findings in boxes, as if they wanted to bind them).

What is certainly going to stir controversy is the finding that while long term growth is negatively affected by product market regulation, excessive labour market regulation does not hamper long term performance.

It is not the first time that the IMF surprises us with interesting analysis that goes against its own previous conventional wisdom. I will write more about this shortly. Here I just want to remark how these findings are relevant for our old continent.

The austerity imposed to embraced by eurozone crisis countries has taken the shape of expenditure cuts and labour market deregulation, whose magic effects on growth and competitiveness have been sold to reluctant and exhausted populations as the path to a bright future. I already noted, two years ago, that the short-run pain was slowly evolving into long-run pain as well, and that the gain of structural reforms was nowhere to be seen. The IMF tells us, today, that this was to be expected.

The guy who should be happy is Alexis Tsipras; he has been resisting since January pressure from his peers (and the Troika, that includes IMF staff!) to further curb labour market regulations, and recently presented a list of reforms that mostly pledges to reduce crony capitalism, tax evasion and product market rigidities. Exactly what the IMF shows to be effective in boosting growth. Of course, at the opposite, those who spent their political capital to implement labour market reforms are most probably not rejoicing at the IMF findings.

This happens in Washington. Problem is, Greece, and Europe at large, seem to be light years away from the IMF research department. We already saw, for example with the mea culpa on multipliers, that IMF staff in program countries does not necessarily read what is written at home. Let’s see whether the discussion on Greece’s reforms will mark a realignment between the Fund’s research work and the prescriptions they implement/suggest/impose on the ground.

Commission Forecasts Watch – November 2014 Edition

Update (11/10): Well, I typed a few numbers wrong, for France and Finland (thanks to Tadej Kotnik for pointing this out). I corrected the data, and stroke down the remarks on Finland that with the corrected data does not beat the expectations. Apologies to the readers

Today the Commission issued its Autumn forecast. It is therefore time to update my forecast watch. Here it is:

Last March, my crystal ball gave me a forecasted growth of 0.55% for the EMU, while the Commission forecasted 1.2% (In March it was 1.1% but it had then been revised in May). As of today (if things do not get worse, in which case I will be even closer), my forecast error is -0.25%, and the Commission’s is +0.4% I win, the Commission loses.

After 2013, when they were remarkably close, Commission forecasts seem to have diverged once more, at least last Spring. We’ll have to see what the final figure for 2014 is (My crystal ball forecast update gives 0.65%).

But besides playing with numbers, the interesting thing about this year’s Autumn forecasts, is that growth has been revised downwards especially for core countries.

In particular since last Spring the mood has changed about Germany, whose growth forecast has been slashed of 0.5% for 2014 (in just a few months, it is worth reminding it), and of 0.9% (almost halved) for 2015. Also interestingly, the only core country whose expectations have been revised upwards, Finland, is also the only one that got rid of its excess savings and current account surplus.

We all know that the disappointing performance of Germany is due, mostly, to geopolitical uncertainty and low growth in emerging economies. When will our German friends understand that putting all eggs in the basket of foreign demand is risky?