Archive

Wolfgang Schäuble’s Ideas are Alive and Kicking

[As usual lately, this is an English AI translation of a piece written for the Italian Daily Domani]

Wolfgang Schäuble was a central figure in the German political landscape. A member of parliament for the centre-right Christian Democrats party from 1972 until his death on Tuesday evening at the age of 81, he was very close to Chancellor Helmut Kohl and, as a lawyer, one of the negotiators of the treaty that brought about the reunification with East Germany. But it was with Angela Merkel as Chancellor that Schäuble became known beyond national borders. For a few years Minister of the Interior, he was appointed Minister of Finance in 2009, a few weeks before the revelations about the state of Greek public finances that triggered the sovereign debt crisis. Since then, he has been one of the central figures in the calamitous management of the crisis. A staunch pro-European, he has nevertheless always been convinced, in homage to the ordoliberal doctrine, that integration could only be achieved by harnessing the European economy in a dense network of rules that would guarantee the public and private thrift necessary to make the EU competitive on world markets. Schäuble was the main standard-bearer of the “Berlin View” (or Brussels or Frankfurt, being adopted by the heads of the European Commission and the ECB of the time) which attributed the debt crisis to the fiscal profligacy and lack of reforms of the so-called “peripheral” EMU countries. A narrative about the crisis that forced “homework” (austerity and structural reforms) on the countries in crisis: we owe to Schäuble’s intransigence, backed by Angela Merkel, the Commission and the ECB (and sometimes against the IMF, which often had a more pragmatic approach), the draconian conditions imposed on Greek governments in exchange for financial assistance from the so-called Troika. In those years, he and the then president of the ECB, Jean-Claude Trichet, argued, against all empirical evidence, for expansionary austerity, the idea that fiscal restriction would supposedly free markets’ animal spirits and thus revive growth. An austerity that Schäuble imposed on countries in crisis but also followed at home. On the occasion of his departure from the Ministry of Finance in 2017, the photo of the employees forming a large zero in the courtyard in homage to the achievement of a balanced budget objective went around the world.

History has taken it upon itself to show the ineffectiveness and cost of that strategy. Not surprisingly, austerity is almost never expansionary and certainly has not been so in the eurozone. The fiscal adjustment imposed on the EMU peripheral countries triggered a crisis which for some of them had not yet been absorbed by the end of the decade. A crisis that, moreover, could have been less painful if the countries in better shape had supported the eurozone growth with expansionary policies, instead of adopting a restrictive stance themselves. The EMU is the only large advanced economy that suffered a second recession in 2012-13, after the Global Financial crisis of 2008. Not only that: since then, domestic demand has remained anaemic, and the European economy has become “Germanized”, managing to grow only thanks to exports; this contributes to the growing trade tensions, and Germany stands accused by international bodies and by the United States of exerting deflationary pressure on the world economy.

The narrative of a crisis caused by the fiscal irresponsibility of spendthrift governments quickly lost its luster and already in 2014 many of its initial supporters (e.g. Mario Draghi, who in the meantime became president of the ECB) opted for a more “symmetrical” explanation, according to which the trigger of the crisis were balance of payments imbalances of which the over-spendthrift and the over-austere countries were equally guilty. But Schäuble never backed from his belief that the only necessary medicine was the downsizing of public spending; Germany also imposed this view to its partner when reforming the European institutions (from the ESM to the fiscal compact).

With the Covid crisis and Germany’s staunch support for Next Generation EU, it seemed that the ordoliberal doctrine finally went into retirement, along with Schäuble, its proudest partisan. But recent events show us that this was wishful thinking. Schäuble would probably have approved the (non-)reform of the Stability Pact imposed by his successor Lindner, whose only guiding light is the reduction of public debt. Schäuble has left us, but the fetish of public and private thrift as a healing virtue is alive and well.

Killing Them Softly?

Just a very quick and unstructured note on Greece. There is lots of confusion under the sky, and it seems to me that creditors are today advancing in sparse order.

Yesterday something rather upsetting happened, as the Eurogroup suspended bailout payments because Greece engaged in some extra expenditures. These are mostly targeted to pensioneers and to the Greek islands that had to endure unexpected costs linked to the refugee crisis. Unexpectedly, the Commission is siding with Greece, with Pierre Moscovici arguing that the country is on target, and that its effort has been remarkable so far. In fact, I have understood, Greece is doing so well that it overshot the target of structural surplus for 2016, and it it these extra resources that it is engaging in order to soft the impact of austerity.

And then there is the IMF, accused by Greece of pushing for more austerity, is also under attack from EU institutions (Eurogroup and Commission) for its refusal to join the bailout package. The Fund has hit back, in a somewhat irritual blog post signed by Maurice Obstfeld and Poul Thomsen (not just any two staffers) and seems not to be available to play the scapegoat for a program that in their opinion was born flawed. In fact, I think that more than to Greece, Obstfeld and Thomsen have written with the other creditors in mind.

I have two considerations, one on the economics of all this, one on the politics.

- I think I will side with the IMF on this. At least with the recent IMF. Since the very beginning The IMF has dubbed as irrealistic the bailout package agreed after the referendum of 2015 . The effort demanded to Greece (the infamous 3.5% structural surplus to be reached by 2018) was recognized to be self-defeating, and the IMF asked for more emphasis on reform, with in exchange a more lenient and realistic approach to fiscal policy: debt relief and much lower required suprluses (1.5% of GDP). In other words, the IMF seems to have learnt from the self-defeating austerity disaster of 2010-2014, and to have finally an eye to the macroeconomic consistency of the reform package. I still believe that the bailout should have been unconditional, and require reforms once the economy had recovered (sequencing, sequencing, and sequencing again). But still, at least the IMF now has a coherent position. Moscovici’s FT piece linked above also seems to go in the same direction, arguing that nothing more can be asked to Greece. It falls short of acknowledging that the package is unrealistic, but at least it avoids blaming the country. And then there is the Eurogroup, actually, Mr Dijsselbloem and Schauble (let’s name names), that did not move an inch since 2010, and fail to see that their demands are slowly (?) choking the Greek economy, stifling any effort to soften the hardship of the adjustment.

- The political consideration is that the hawks still give the cards, as they dominate the eurogroup. But they are more isolated now. Evidence is piling that the eurozone crisis has been mismanaged to an extent that is impossible to hide, and that the austerity-reforms package that the Berlin View has imposed to the whole eurozone is a big part of the explanation for the political disgregation that we see across the continent. The more nuanced position of the Commission, the IMF challenge to the policies dictated by the hawks, therefore represent an opportunity. There is a clear political space for an alternative to the Berlin View and to the disastrous policies followed so far. The question is which government will be willing (and able) to rise to the occasion. I am afraid I know the anwser.

The Quest for Discretionary Fiscal Policy

It is nice to resume blogging after a quite hectic Fall semester. Things do not seem to have gotten better in the meantime…

The EMU policy debate in the past few months kept revolving around monetary policy. Just this morning I read a Financial Times report on the never ending struggle between hawks and doves within the ECB. I am all for continued monetary stimulus. It cannot hurt. But there is only so much monetary policy can do in a liquidity trap. I said it many times in the past (I am in very good company, by the way), and nothing so far proved me wrong.

A useful reminder of how important fiscal policy is, and therefore of how criminal it is to willingly decide to give it up, comes from a recent piece from Blinder and Zandi, who tried to assess what the US GDP trajectory would have been, had the discretionary policy measures implemented since 2008 not been in place. I made a figure of their counterfactual:

It is worth just using their own words:

Without the policy responses of late 2008 and early 2009, we estimate that:

- The peak-to-trough decline in real gross domestic product (GDP), which was barely over 4%, would have been close to a stunning 14%;

- The economy would have contracted for more than three years, more than twice as long as it did;

- More than 17 million jobs would have been lost, about twice the actual number.

- Unemployment would have peaked at just under 16%, rather than the actual 10%;

- The budget deficit would have grown to more than 20 percent of GDP, about double its actual peak of 10 percent, topping off at $2.8 trillion in fiscal 2011.

- Today’s economy might be far weaker than it is — with real GDP in the second quarter of 2015 about $800 billion lower than its actual level, 3.6 million fewer jobs, and unemployment at a still-dizzying 7.6%.

We estimate that, due to the fiscal and financial responses of policymakers (the latter of which includes the Federal Reserve), real GDP was 16.3% higher in 2011 than it would have been. Unemployment was almost seven percentage points lower that year than it would have been, with about 10 million more jobs.

The conclusion I draw is unequivocal: Blinder and Zandi give yet another proof that what made the current recession different from the tragedy of the 1930s it the swift and bold policy reaction.

This of course nothing new. But unfortunately, it sounds completely heretic in European policy circles. In my latest post (internet ages ago) I noticed that how little Mario Draghi’s position on fiscal matters differed from Angela Merkel’s, and in general from the European pre-crisis consensus.

The reader will have noticed that in the figure above I also drew EMU12 real GDP. It did not fall as much as the US no-policy counterfactual (among other things because exports kept us afloat thanks to…the US recovery). But we are today stuck in a semi-permanent state of stagnant growth. EMU12 GDP is today at the same level as the level the US would have had, had their policies been completely inertial. Once again, a visual aid:

I already showed this figure in the past. On the x-axis you have the output gap, i.e. a measure of how deep in a recession the economy is. On the y-axis you have he fiscal impulse, i.e. a measure of discretionary fiscal policy (net of interest payment and of cyclical adjustment of government deficit). A well functioning fiscal policy would result in a negative correlation: If the economy goes down (negative output gap), fiscal policy is expansionary (positive fiscal impulse). This is what actually happened in 2008-2009 (red series). But then as we know European policy makers succumbed to the fairy tale of expansionary fiscal consolidations, and fiscal policy turned pro-cyclical (yellow series). A persisting output gap was met with fiscal consolidation (improvement in structural fiscal balance).

Overall, policy was neutral. This is consistent with the Berlin View, that fears discretionary policies as if they were the plague. And explains much of our dismal performance. The fact that we are close to Blinder and Zandi’s “no-policy” scenario is no coincidence at all. Our policy makers should look at their blue line for the US, and realize that we could be around there too, if only they were less stubbornly ideological.

Draghi the Fiscal Hawk

We are becoming accustomed to European policy makers’ schizophrenia, so when yesterday during his press conference Mario Draghi mentioned the consolidating recovery while announcing further easing in December, nobody winced. Draghi’s call for expansionary fiscal policies was instead noticed, and appreciated. I suggest some caution. Let’s look at Draghi’s words:

Fiscal policies should support the economic recovery, while remaining in compliance with the EU’s fiscal rules. Full and consistent implementation of the Stability and Growth Pact is crucial for confidence in our fiscal framework. At the same time, all countries should strive for a growth-friendly composition of fiscal policies.

During the Q&A, the first question was on precisely this point:

Question: If I could ask you to develop the last point that you made. Governor Nowotny last week said that monetary policy may be coming up to its limits and perhaps it was up to fiscal policy to loosen a little bit to provide a bit of accommodation. Could you share your thoughts on this and perhaps even touch on the Italian budget?

(Here is the link to Austrian Central Bank Governor Nowotny making a strong statement in favour of expansionary fiscal policy). Draghi simply did not answer on fiscal policy (nor on the Italian budget, by the way). The quote is long but worth reading

Draghi: On the first issue, I’m really commenting only on monetary policy, and as we said in the last part of the introductory statement, monetary policy shouldn’t be the only game in town, but this can be viewed in a variety of ways, one of which is the way in which our colleague actually explored in examining the situation, but there are other ways. Like, for example, as we’ve said several times, the structural reforms are essential. Monetary policy is focused on maintaining price stability over the medium term, and its accommodative monetary stance supports economic activity. However, in order to reap the full benefits of our monetary policy measures, other policy areas must contribute decisively. So here we stress the high structural unemployment and the low potential output growth in the euro area as the main situations which we have to address. The ongoing cyclical recovery should be supported by effective structural policies. But there may be other points of view on this. The point is that monetary policy can support and is actually supporting a cyclical economic recovery. We have to address also the structural components of this recovery, so that we can actually move from a cyclical recovery to a structural recovery. Let’s not forget that even before the financial crisis, unemployment has been traditionally very high in the euro area and many of the structural weaknesses have been there before.

Carefully avoiding to mention fiscal policy, when answering a question on fiscal policy, speaks for itself. In fact, saying that “Fiscal policies should support the economic recovery, while remaining in compliance with the EU’s fiscal rules” and putting forward for the n-th time the confidence fairy, amounts to a substantial approval of the policies followed by EMU countries so far. We should stop fooling ourselves: Within the existing rules there is no margin for a meaningful fiscal expansion of the kind invoked by Governor Nowotny. If we look at headline deficit, forecast to be at 2% in 2015, the Maastricht limits leave room for a global fiscal expansion of 1% of GDP, decent but not a game changer (without mentioning the fiscal space of individual countries, very unevenly distributed). And if we look at the main indicator of fiscal effort put forward by the fiscal compact, the cyclical adjusted deficit, the eurozone as a whole should keep its fiscal consolidation effort going, to bring the deficit down from its current level of 0.9% of GDP to the target of 0.5%.

It is no surprise then that the new Italian budget (on which Mario Draghi carefully avoided to comment) is hailed (or decried) as expansionary simply because it slows a little (and just a little) the pace of fiscal consolidation. Within the rules forcefully defended by Draghi, this is the best countries can do. As a side note, I blame the Italian (and the French) government for deciding to play within the existing framework. Bargaining a decimal of deficit here and there will not lift our economies out of their disappointing growth; and more importantly, on a longer term perspective, it will not help advance the debate on the appropriate governance of the eurozone.

In spite of widespread recognition that aggregate demand is too low, Mario Draghi did not move an inch from his previous beliefs: the key for growth is structural reforms, and structural reforms alone. He keeps embracing the Berlin View. The only substantial difference between Draghi and ECB hawks is his belief that, in the current cyclical position, structural reforms should be eased by accommodating monetary policy. This is the only rationale for QE. Is this enough to define him a dove?

EMU Troubles: The Narrow Way Out

I was asked to write a piece on whether we should continue to study the EMU (my answer is yes. In case you wonder, this is called vested interest). One section of it can be a stand-alone blog post: Here it is, with just a few edits:

While in the late 1980s the consensus among economists and policy makers was that the EMU was not an optimal currency area (De Grauwe, 2006), the choice was made to proceed with the single currency for two essentially opposed reasons: The first, stemming from the Berlin-Brussels Consensus, saw monetary integration, together with the establishment of institutions limiting fiscal and monetary policy activism, as an incentive for pursuing structural reforms and converging towards market efficiency: as the role of macroeconomic management was believed to be limited, giving up monetary policy would impose negligible costs to countries while forcing them, through competition, to remove growth-stifling obstacles to markets.

Another group of academics and policy makers, while not necessarily subscribing to the Consensus, highlighted the political economy of the single currency: Adopting the euro in a non-optimal currency area would have created the incentives for completing it with a political union: a federation, endowed with a common fiscal policy and capable of implementing the fiscal transfers that are required to avoid divergence. In other words a non-optimal euro was seen as just an intermediate step towards a real United States of Europe. A key argument of the proponents of a federal Europe was, and still is, that fiscal transfers seem unavoidable to ensure economic convergence. A seminal paper by Sala-i-Martin and Sachs (1991) shows that even in the United States, where market flexibility is substantially larger than in the EMU, transfers from booming states to states in crisis account for almost 50% of the reaction to asymmetric shocks.

It is interesting to notice how the hopes of both views were dashed by subsequent events. As the theory of optimal currency areas correctly predicted, the inception of the euro without sufficiently strong correction mechanisms, triggered a divergence between a core, characterized by excess savings and export-led growth, and a periphery that sustained the Eurozone growth through debt-driven (public and private) consumption and investment.

Even before the crisis the federal project failed to make it into the political agenda. The euro came to be seen by the political elites not, as the federalists hoped, as an intermediate step towards closer integration, but rather as the endpoint of the process initiated by Jean Monnet and Robert Schuman in 1950. The crisis further deepened economic divergence and recrimination, highlighting national self-interest as the driving force of policy makers, and making solidarity an empty word. As we write, the Greek crisis management, the refugee emergency, the centrifugal forces shaking Europe, are seen as a potential threat to the Union, rather than a push for further integration as it happened in the past (Rachman, 2015).

The Consensus partisans won the policy debate. The EMU institutions, banning discretionary policy, reflect their intellectual framework; and the policies followed (more or less willingly) by EMU countries, especially since the crisis, are the logical consequences of the consensus: austerity and structural reforms aimed at increasing competitiveness and reducing the weight of the State in the economy. But while they can rejoice of their victory, Consensus proponents have to deal with the failure of their policies: five years of Berlin View therapy has nearly killed the patient. Peripheral countries’ debt is still unsustainable, growth is nowhere to be seen (including in successful Germany), and social hardship is reaching unbearable levels (Kentikelenis et al., 2014). Coupling austerity with reforms proved to be self-defeating, as the short term recessionary impact on the economy was much larger than expected (Blanchard and Leigh, 2013), and as a consequence the long run benefits failed to materialize (Eggertsson et al., 2014). It is then no surprise that in spite of austerity and reforms, divergence between the core and the periphery of the Eurozone is even larger today than it was in 2007.

The dire state of the Eurozone economy is in some sense the revenge of optimal currency areas theory, with a twist. It appears evident today, but it was clear two decades ago, that market flexibility alone would never suffice to ensure convergence (rather the opposite), so that the Consensus faces a potentially fatal challenge. On the other hand, the federalist project, that was already faltering, seems to have received a fatal blow from the crisis.

The conclusion I draw from these somewhat trivial considerations is that the EMU is walking a fine line. If the federalist project is dead, and if Consensus policies are killing the EMU, what have we left, besides a dissolution of the euro?

I conclude the paper by arguing that two pillars of a new EMU governance/policy are necessary (neither of them in isolation would suffice):

- Putting in place any possible surrogate of fiscal transfers, like for example a EU wide unemployment benefit, making sure that it is designed to be politically feasible (i.e. no country is net contributor on average), eurobonds, etc.

- Scrapping the Consensus together with its foundation, the efficient market hypothesis, and head towards real, flexible coordination of (imperfect) macroeconomic policies in order to deal with (imperfect) markets. Government by the rules only works in the ideal neoclassical world.

I know, more easily said than done. But I see no other possibility.

And the Winner is (should be)…. Fiscal Policy!

So, Mario Draghi is disappointed by eurozone growth, and is ready to step up the ECB quantitative easing program. The monetary expansion apparently is not working out as planned.

Big surprise. I am afraid some people do not have access to Wikipedia. If they had, they would read, under “liquidity trap“, the following:

A liquidity trap is a situation, described in Keynesian economics, in which injections of cash into the private banking system by a central bank fail to decrease interest rates and hence make monetary policy ineffective. A liquidity trap is caused when people hoard cash because they expect an adverse event such as deflation, insufficient aggregate demand, or war.

In a liquidity trap the propensity to hoard of the private sector becomes virtually unlimited, so that monetary policy (be it conventional or unconventional) loses traction. It is true that the age of great moderation, and three decades of almighty central bankers had made the concept fade into oblivion. But, since 2008 we were forced to reconsider the effectiveness of monetary policy at the so-called zero lower bound.Or at least we should have…

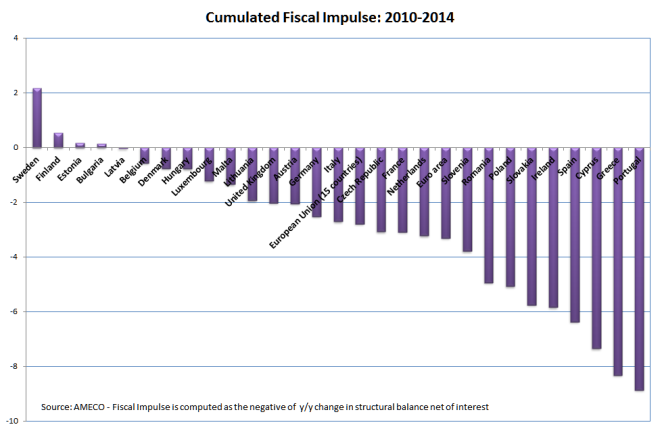

So, had policy makers taken the time to look at the history of the great depression, or at least to open the Wikipedia entry, they should have learnt that when monetary policy loses traction, the witness in lifting the economy out of the recession, needs to be taken by fiscal policy. In a liquidity trap the winner is fiscal policy. Or at least it should be. Here is a measure of the fiscal stance, computed as the change in government balance once we exclude cyclical components and interest payments.

The vast majority of E

The vast majority of EMU countries undertook a strong fiscal tightening, regardless of the actual health of their public finances. This generalized austerity, an offspring of the Berlin View, led to our double dip recession, and to further divergence in the eurozone, that would have needed coordinated, not synchronized fiscal policies. Well done guys…

And yet, Mario Draghi is surprised by the impact of QE.

Of Democracy and of a Different Europe

I have mixed feeling about the Oki victory in Greece. The choice was between two evils: slow death by more of the same (the troika plan), or a roller-coaster ride that has a high chance of ending catastrophically for Greece and for the EMU. I would have voted no, were I Greek, but not joyfully. This said, two things I have been reading in the past days are disturbing:

- First, the claim that Tsipras’ rhetoric on democracy is misplaced: After all, people say, we all are democracies. Why should Greek democracy count more than the Portuguese, or the Spanish one? There is no reason, of course. Point is that Tsipras did something that is now really revolutionary in Europe, he tried – hold your breath – to implement the platform on which he was elected. How many governments in Europe went to power promising an end to austerity, promising a “new deal for Europe”, just to retract a few months/weeks/days later and align themselves with the Berlin View that austerity is the only way? Greek democracy today should count more than democracy in the rest of Europe, because it is the only case in which voters are actually listened to by their government. This is why Syriza’s anomaly needed to be crushed, well beyond the actual content of its proposed policies. If European policy makers feel that their democracy should be as important as Greece’s, they could start by trying to do what their voters elected them for. That would certainly not hurt.

- The second thing that bothers me, is the convergence of the establishment and of euro-skeptical movements across Europe. Don’t be fooled by the enthusiastic adherence of many no-euro movements to the Oki campaign Their siding with Tsipras was instrumental to Grexit, turmoil, and weakening the euro itself. Something orthogonal to what Tsipras has been doing and saying in the past two years. The referendum made it clear that the establishment and the no-euro converge in trying to prove that there is no alternative to austerity in Europe. The former, because if Greece is not normalized, we would enter into a new phase in which statements and policies would have to be assessed on the basis of facts (not so favorable to austerity) rather than taken as a matter of faith. Euro skeptics need Tsipras to be crushed because this would definitely prove that the only way to get rid of austerity is to get rid of the euro altogether.

Therefore the referendum, while certainly hazardous and ill-conceived (what did the Greek people vote on, in the end?), had the great merit of exposing the hypocrisy of some commentators, and to show that the only hope for a different Europe has to be found in the struggle that an inexperienced prime minister is leading from Athens. Since yesterday, with the renewed support of his people. Dangerous times ahead, but with a small hope for change.

Reform or Perish

Very busy period. Plus, it is kind of tiresome to comment daily ups and downs of the negotiation between Greece and the Troika Institutions.

But as yesterday we made another step towards Grexit, it struck me how close the two sides are on the most controversial issue, primary surplus. Greece conceded to the creditors’ demand of a 1% surplus in 2015, and there still is a difference on the target for 2016, of about 0.5% (around 900 millions). Just look at how often most countries, not just Greece, respected their targets in the past, and you’ll understand how this does not look like a difference impossible to bridge.

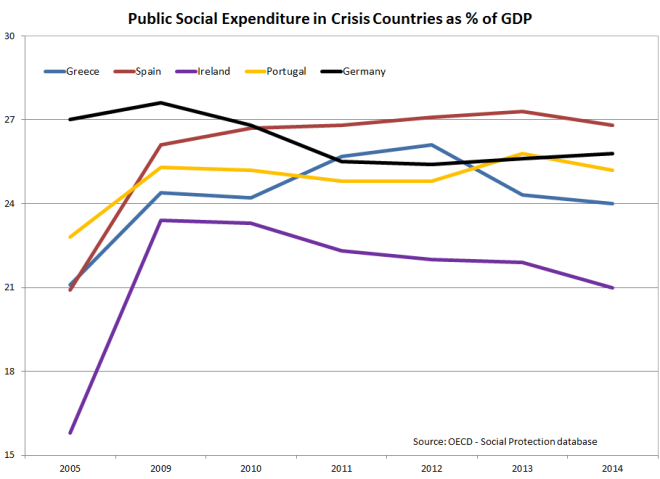

The remaining issue is reforms. Creditors argue that Greece cannot be trusted in its commitment to reform. After all, they cheated so often in the past… In particular, creditors point at one of Syriza’s red lines, the refusal to touch pension reforms, as proof that the country is structurally incapable of reform. And here is the proof, the percentage of GDP that crisis countries spent in welfare::

I took total social expenditure that bundles together pensions, expenditure for supporting families, labour market policies, and so on and so forth. All these expenditure that, according to the Berlin View, choke the animal spirits of the economy, and kill productivity.

Well, Greece does not do much worse than its fellow crisis economies, but it is true that it is hard to detect a downward trend. The reform effort was not very strong, and certaiinly not adapted to an economy undergoing such a terrible crisis. The very fact that after four years of adjustment program the country spends 24% of its GDP in social protection, is a proof that it cannot be trusted.This is just proof that, once more, the Greek made fun of their fellow Europeans, and that they want us to pay for their pensions.

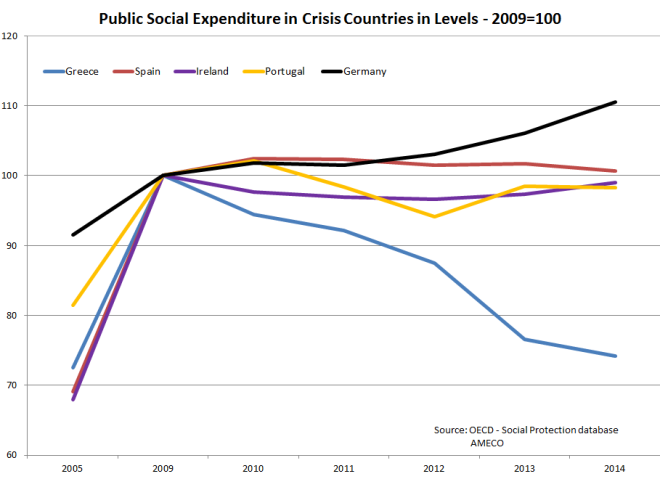

Hold on. Did I just say “terrible crisis”? What was that story of ratios, denominators and numerators? The ratio is today at the same level as 2009. But what about actual expenditure? There is a vary simple way to check for this. Multiply each of the lines above for the value of GDP. Here is what you get (normalized at 2009=100, as country sizes are too different):

The picture looks quite different, does it? Greece, whose crisis was significantly worse than for the other countries, slashed social expenditure by 25% in 5 years (I know, I know, it is current expenditure. I am too busy to deflate the figure. But I challenge you to prove that things would be substantially different). Now, just in case you had not noticed, social expenditure has an important role as an automatic stabilizer: It supports incomes, thus making hardship more bearable, and lying the foundations for the recovery. In a crisis the line should go up, not down. This picture is yet another illustration of the Greek tragedy, and of the stupidity of the policies that the Troika insists on imposing. By the way, notice how expenditure increased from 2005 to 2009, in response to the global financial crisis. A further proof that sensible policies were implemented in the early phase of the crisis, and that we went berserk only in the second phase.

Ah, and of course virtuous Germany, the model we should all follow, is the black line. Do what I say…

One may object that focusing on expenditure is misleading. There is more than expenditure in assessing the burden of the welfare state on the economy. While Greece slashed spending, its welfare state did not become any better; its capacity to collect taxes did not improve, that its inefficient public administration and its crony capitalism are stronger than ever. Yes, somebody may object all that. That someone is Yanis Varoufakis, who is demanding precisely this: stop asking that Greece slashes spending, and lift the financial constraint that prevents any meaningful medium term reform effort. Reform is not just cutting expenditure. Reform is reorganization of the administrative machine, elimination of wasteful programs, redesigning of incentives. All that is a billion times harder to do for a government that spends all its energies finding money to pay its debt.

Real reform is a medium term objective that needs time, and sometimes resources. In a sentence, reform should stop being associated with austerity.

But hey, I am no finance minister. Just sayin’…

Mr Sinn on EMU Core Countries’ Inflation

Two weeks ago I received a request from Prof Sinn to make it known to my readers that he feels misrepresented by my post of September 29. Here is his very civilized mail, that I publish with his permission:

Dear Mr. Saraceno,

I have just become acquainted with your blog: https://fsaraceno.wordpress.com/2014/09/29/draghi-the-euro-breaker/. You misrepresent me here. In my book The Euro Trap. On Bursting Bubbles, Budgets and Beliefs, Oxford University Press 2014, and in many other writings, I advise against extreme deflation scenarios for southern Europe because of the grievous effects upon debtors. I explicitly draw the comparison with Germany in the 1929 – 1933 period. I advocate instead a mixed solution with moderate deflation in southern Europe and more inflation in northern Europe, Germany in particular. In addition, I advocate a debt conference for southern Europe and a “breathing currency union” which allows for temporary exits of those southern European countries for which the stress of an internal adjustment would be unbearable. You may also wish to consult my paper “Austerity, Growth and Inflation: Remarks on the Eurozone’s Unresolved Competitiveness Problem”, The World Economy 37, 2014, p. 1-1, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/twec.2014.37.issue-1/issuetoc, in which I also argue for more inflation in Germany to solve the Eurozone’s problem of distorted relative prices. I would be glad if you could make this response known to your readers.Sincerely yours

Hans-Werner Sinn

Professor of Economics and Public Finance

President of CESifo Group

I was swamped with end of semester duties, and I only managed to read the paper (not the book) this morning. But in spite of Mr Sinn’s polite remarks, I stand by my statement (spoiler alert: the readers will find very little new content here). True, in the paper Mr Sinn advocates some inflation in the core (look at sections 9 an 10). In particular, he argues that

What the Eurozone needs for its internal realignment is a demand-driven boom in the core countries. Such a boom would also increase wages and prices, but it would do so because of demand rather that supply effects. Such demand-driven wage and price increases would come through real and nominal income increases in the core and increasing imports from other countries, and at the same time, they would undermine the competitiveness of exports. Both effects would undoubtedly work to reduce the current account surpluses in the core and the deficits in the south.

This is a diagnosis that we share But the agreement stops around here. Where we disagree is on how to trigger the demand-driven boom. Mr Sinn expects this to happen thanks to market mechanisms, just because of the reversal of capital flows that the crisis triggered. He argues that the capital which foolishly left Germany to be invested in peripheral countries, being repatriated would trigger an investment and property boom in Germany, that would reduce German’s current account surplus. This and this alone would be needed. Not a policy of wage increases, useless, nor a fiscal expansion even more useless.

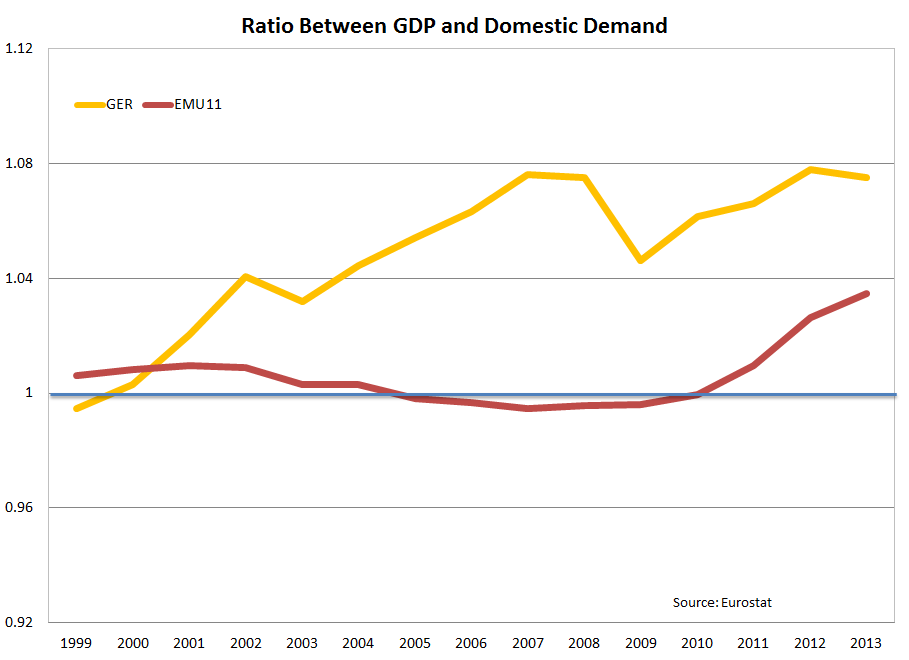

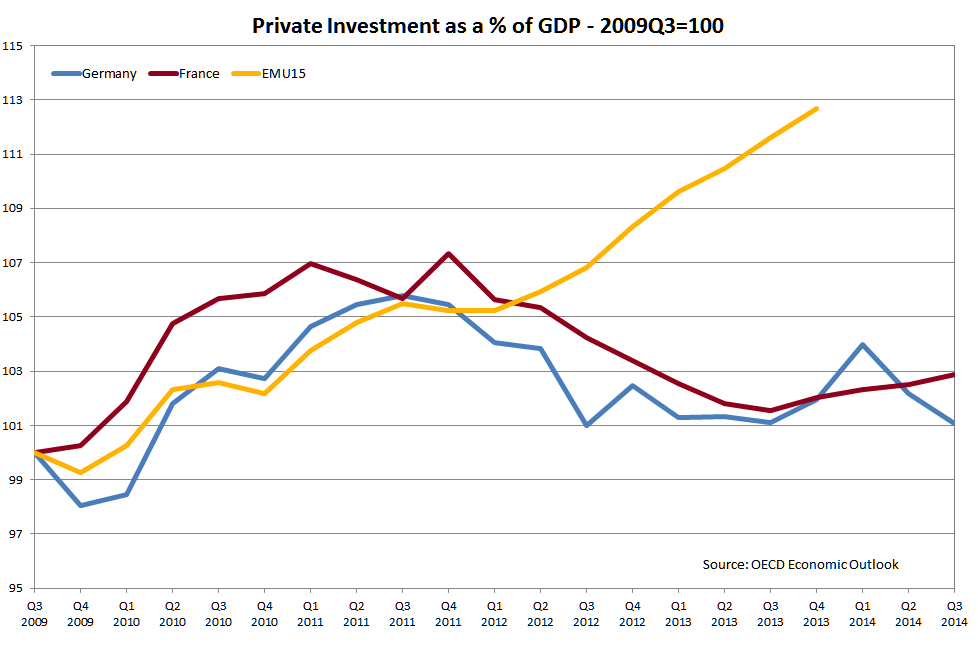

Problem is, the data speak against Mr Sinn’s belief. Since the crisis hit, capital massively left peripheral countries, and yet this did not fuel domestic demand in Germany. Last August I showed the following figure:

It shows that after a drop (in the acute phase of the financial crisis) due to a sharp decline of GDP, since 2009 domestic demand as a percentage of GDP kept decreasing, in Germany as well as in the rest of the Eurozone. The reversal of capital flows depressed demand in the periphery, but did not boost it in Germany. Mr Sinn is too skilled an economist to fail to see this. The reason is, of course, that the magic investment boom did not happen:

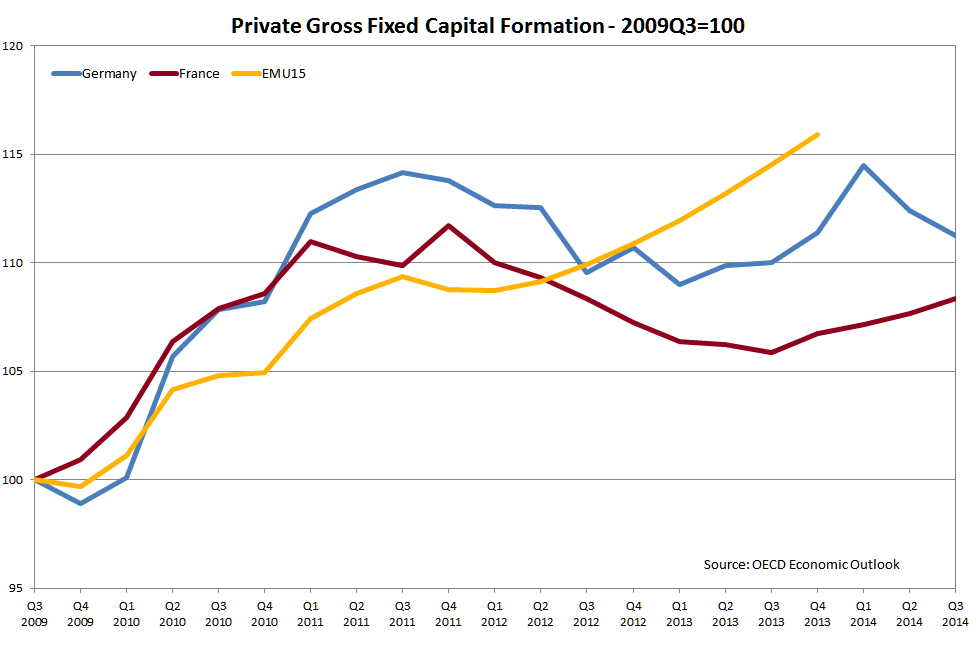

Mr Sinn, being a fine economist, could object that this is because GDP, the denominator, grew more

Mr Sinn, being a fine economist, could object that this is because GDP, the denominator, grew more fell less in Germany than in the rest of the EMU. Well, think again.

Yes, France comes out as investing (privately) less than Germany. But we are far from an investment boom in Germany as well. Mr Sinn, will agree, I ma sure.

Yes, France comes out as investing (privately) less than Germany. But we are far from an investment boom in Germany as well. Mr Sinn, will agree, I ma sure.

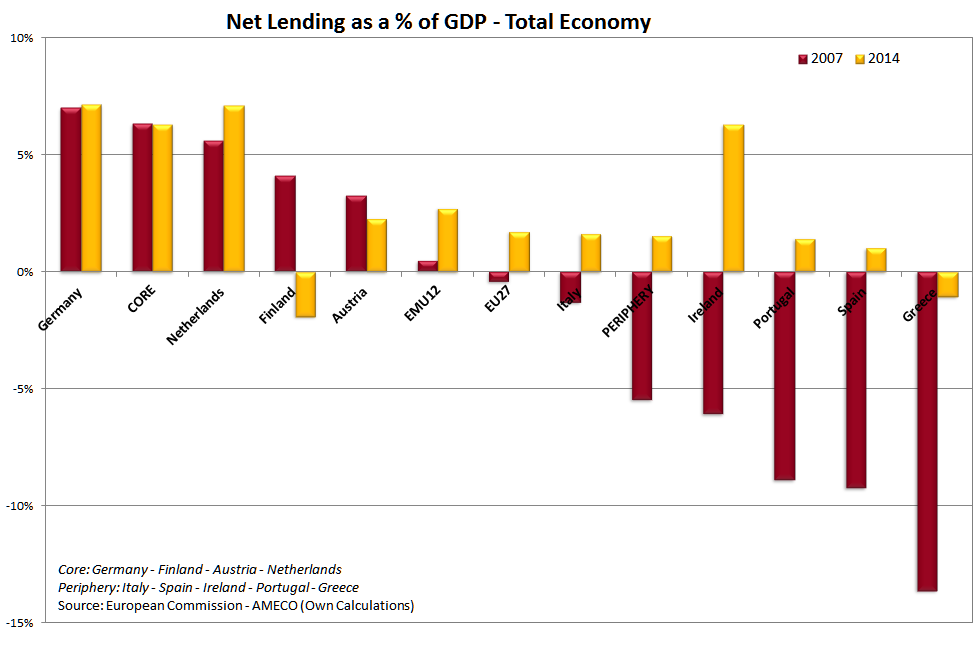

What basically happened, I said it before, is that adjustment was not symmetric. Peripheral countries reduced their excess demand, while Germany and the core did not reduce their excess savings. The result is that, if we compare 2007 to 2014, external imbalances of the periphery were greatly reduced or reversed, while with the exception of Finland the core did not do its homework:

The EMU as a whole became a large Germany, running a current account surplus (it was more or less in balance in 2007), and relying on its exports for growth. A very dubious strategy in the long run.

The EMU as a whole became a large Germany, running a current account surplus (it was more or less in balance in 2007), and relying on its exports for growth. A very dubious strategy in the long run.

The conclusion in my opinion is one and only one: We cannot count on markets alone, in the current macroeconomic situation, if we want rebalancing to take place. In the article he suggested I read, Mr Sinn states that a 4 or 5 per cent inflation rate would be politically impossible to sell to the German public:

Moreover, it is unclear whether the German population would accept being deprived of their savings. Given the devastating experiences Germany made with hyperinflation from 1914 to 1923, which in the end undermined the stability of its society, the resistance against an extended period of inflation in Germany could be as strong or even stronger than the resistance against deflation in southern Europe. After all, a rate of 4.1 per cent for German inflation for 10 years, which would be necessary to allow the necessary realignment between France and Germany without France sliding into a deflation, would mean that the German price level would increase by 50 per cent and that, in terms of domestic goods, German savers would be deprived of 33 per cent of their wealth. If the German inflation rate were even 5.5 per cent, which would be necessary to accommodate the Spanish realignment without price cuts, its price level would increase by 71 per cent over a decade and German savers would be deprived of 42 per cent of their wealth.

This shows all the logic of Ordoliberalism: It is impossible to sell inflation to the the German public, because this would deprive them of their savings. This argument only makes sense if one subscribes to the Berlin View that the bad guys in the south partied with hard earned money of northern (hard) workers. Otherwise the argument makes no sense at all, as high inflation in the core for next few years simply compensates low inflation in the past. Should I remind Mr Sinn that the outlier in terms of labour costs is not the EMU periphery, but Germany?

Also, I find it disturbing that, while acknowledging that inflation in Germany would be needed, Mr Sinn rejects it on the ground that it would be a hard sell. The role of intellectuals and academics is mostly to discuss, find solutions (or at least try), and then argue for them. All the more so if this is unpopular, because it is then that their pedagogical role is most needed. All too often public intellectuals abdicate to their role, and simply follow the trend. Should we all argue in favour of a euro breakup only because public opinion is less and less favorable to the single currency?

Finally, a short comment on another bit of Mr Sinn’s article:

And although the core countries would suffer [from high inflation], the solution would not be comfortable for the devaluating countries either. They will unavoidably face a long-lasting stagnation with rising mass unemployment and increasing hardship for the population at large. People will turn away from the European idea, and voices opting for exiting the euro will gain strength. Thus, it might be politically impossible to induce the necessary differential inflation in the Eurozone.

I don’t really see his point here. But let’s take it for good, just for the sake of argument. I think it is too late to worry about support for the euro in the periphery. It is hard to see how “excessive” inflation in the core would impose more hardness than seven years of adjustment, ill-conceived structural reforms, and self-defeating austerity.

So Mr Sinn, thank you for your mail and for the reference to your paper that I have read with interest. But no, I don’t think I misrepresented you. The core of your argument remains that the burden of adjustment should rest on the periphery’s shoulders. And you failed to convince me that this is right.

Give Me Some Crowding-Out

I just read, a few days late, a very instructive Op-Ed by Otmar Issing for the Financial Times. The zest of the argument is in the first few lines, that are worth quoting:

Imagine you are asked to give advice to a country on its economic policy. The country enjoys near-full employment; its growth is above, or at least at full potential. There is no under-usage of resources – what economists call an output gap – and the government’s budget is balanced, but the debt level is far above target. To top it all monetary policy is extremely loose.

This is exactly the situation in Germany. Recently forecasts for growth have been revised downwards, but so far the overall assessment is unchanged. At present there is no indication of the country heading towards recession. Inflation is low but there is no risk of deflation. From a purely national point of view Germany needs a much less expansionary monetary policy than it is getting from the European Central Bank. This is a strong argument why fiscal policy should not be expansionary, too.

Where is the economic textbook that argues that such a country should run a deficit to stimulate the economy? There is hardly a convincing argument for such advice.

The quote is a perfect example of what is wrong with mainstream thinking in German academic and policy circles. First, the incapacity to fully appreciate to what extent the German national interest is linked to the wider fate of the eurozone. From a purely national point of view, Germany needs stronger growth in the eurozone, its main trading partner. And it needs higher inflation at home and abroad. Which means that no, monetary policy is not too expansionary for Germany, as Issing claims.

But there is a more important issue: Issing seems not to grasp that the problem with the German economy is that it is unbalanced. True, it is near full employment (even if much could be said about the quality of that employment), but it relies too much on exports and too little on domestic demand, with the result that it runs, since 2001, increasing current account deficits. To say it bluntly, Germany has been sitting on the shoulders of the rest of the world economy, and since 2010 it has been followed by the rest of the eurozone that is globally running trade surpluses. I have already said many times that this is a bad (and dangerous) strategy.

I do not know what textbooks Issing reads. Germany’s intellectual tradition must include OrdoTextBooks. The ones I know say that expansionary fiscal policy, at full employment, crowds out private expenditure and exports. And guess what? This is exactly what Germany should do, for its own and its neighbours’ welfare. And if at the same time private expenditure was also boosted, with wage increases (hey, don’t listen to me; listen to the Bundesbank!) and incentives for investment, crowding out could be limited to foreign demand.

So, I read textbooks and I conclude that Otmar Issing is dead wrong. Germany should boldly expand domestic demand (public and private), thus overheating its economy, crowing out exports, and increasing inflation. The effect would be rebalancing of the German economy, growth in the rest of the eurozone, and relief in the rest of the world, for which we would stop being a drag.

Unfortunately this is not bound to happen anytime soon.