Archive

The Question of Debt Sterilization is not for Today. But it Needs to be Discussed

Yesterday I read an interesting FT piece (signed by the editorial board) arguing against debt cancellation. The piece is interesting and in my opinion its title (The case against cancelling debt at the ECB) is misleading. Summarizing, the piece argues that today countries like Italy have no market access problem, that spreads and interest rates are at an all time low, that debt cancellation would not free cash for Italian immediate needs. This are all reasonable arguments, but they would be relevant in assessing benefits of debt cancellation for a country facing a sovereign debt crisis. The current discussion on debt cancellation is nothing of that sort. It is more similar to debates that in the past were common after extraordinary shocks such as wars or… pandemics.

So, what is wrong with the FT way to approach the issue of debt cancellation (or sterilization, as I would prefer to call it for reasons to be clear below)? First, the excessive focus on Italy is off the mark. Any serious discussion on sterilizing the exceptional debt that was generated by the contrast to the pandemics should concern all EMU countries. All of them have had a spike in deficit and debt. Second, as I said, the piece focuses on the short run arguing that debt sterilization would not bring fresh cash. Of course it would not, and of course it would not be needed. EMU public debt is today (and for a long period to come) in excess demand. On top of that, we learned yesterday to no surprise that the ECB will keep the PEPP umbrella open for a while: March 2022 at the earliest, with no tapering to begin before 2023.

Thus, the discussion should not be on short term market access or liquidity needs (nor on the macroeconomic impact of debt sterilization in the current situation). Sterilizing the EMU pandemics-related public debt is a medium term issue, related to future fiscal space. The question to ask is whether the exceptional stock of debt that built in the past few months will constrain EMU countries in their ordinary fiscal policies in the future. If the answer is yes (I believe it is), then sterilizing that debt is eventually going to be an issue to be dealt with. And in that case it is hard to imagine that the ECB will not be part of the solution. In the end, this is what the FT editorial board seems to suggest too (this is why the piece is more nuanced than the title would make it believe), when they argue that

Italy could act by itself to make its debt easier to deal with over the long run, in case the ECB ever decides to sell its holdings back to the private sector and rates go up. In particular it could issue much longer dated debt to lock in the current low rate of funding, and gain more time to fix the country’s sluggish growth rate. Italy could even try to sell perpetual debt.

In short, the piece suggests that extending the maturity of debt (in principle to perpetuity) should be a strategy for the medium term. If the ECB were to buy that debt, we’d have monetization.

As a side note: The macroeconomic impact of cancellation and of monetization are alike. But cancellation poses a number of (mainly political) issues. I think it is wise to take it off the table and discuss pros and cons of a permanent increase of the ECB balance sheet size. Furthermore, I do not enter into the issue of monetization vs QE (that yielded “reservization”). That issue is very neatly addressed by my colleagues Christophe Blot and Paul Hubert (in French).

The FT editorial board then goes on with a discussion of helicopter money (making a link with debt write-off that I don’t quite see, but whatever) in managing deflationary pressures; once again the verbatim is instructive:

There may be monetary reasons to cancel government debt holdings. Many economists argue that “helicopter money” — a permanent increase in the money supply, likened by the economist Milton Friedman to central bankers dropping cash from a helicopter — will be necessary to rescue the eurozone from potential deflation. This would be most easily enacted by simply writing down the ECB’s existing holdings of government debt to zero. Any move towards this policy should come from central bankers keen to hit their inflation targets and not politicians playing with populist slogans.

What is interesting is the last sentence of the paragraph: The initiative should come from the ECB in pursuing its objectives, not from governments. I made the exact same point a couple of days ago (in Italian, unfortunately). Interestingly, the strong independence of the ECB in this case could help in making the one-off nature of monetization credible and to avoid triggering expectations of fiscal dominance.

So in the end the FT editorial board case against cancellation boils down to timing and to the opportunity that politicians (especially Italians) bring it up now. But the FT acknowledges that the issue of dealing with the Covid related extra debt is on the table and that some sort of ECB sterilization of that debt may in the future be part of the equation.

I am perfectly fine with this article. In spite of the title!

Lagarde: A Rookie Mistake?

So the ECB has spoken in response to the Coronavirus crisis, and it was a problematic response to say the least. I watched Christine Lagarde’s Q&A with journalists, which as usual was the most interesting part of the press conference. But boy, I wish today it had not taken place…

The bottom line is that Lagarde made a huge misstep in stating that the ECB is not going to close the spreads. I hope it is just a communication misstep, otherwise Italy (and probably other countries) will pay a heavy price.

But let’s see what happened today.

First, there is an attempt to put on the Eurozone governments’ shoulders most of the burden of reacting to a shock that will be “significant even if temporary”. Lagarde said clearly, towards the end of the press conference, that what she fears most is insufficient fiscal response coming out from the Eurogroup meeting next Monday:

It is hard to disagree with this approach. To target firms’ liquidity problems one cannot count on banks alone, (especially in countries where they have still not completely recovered from the sovereign debt crisis). As a side note, I welcome the provisions contained in the Italian €25bn package, such as the temporary lifting of short-term businesses obligations towards the government (VAT, social contributions, taxes). These seem to be the right measures to ease short term liquidity constraints.

But let’s look into what the ECB itself commits to do. Besides technicalities that I did not study yet, there will be two sets of measures:

- The first set concerns (continued) provision of cheap liquidity to banks, in order to ensure continuing supply of credit to the real economy. This will be ensured through a new and temporary long-term refinancing scheme (LTRO), together with significantly better terms for the existing targeted loan programs. This amount to a large subsidy to banks. Loans conditions will be more favorable for banks lending to Small and Medium Enterprises, which are the ones more likely to become strapped for liquidity in the current situation. Furthermore, as a supervisor, the ECB engages in operational flexibility when implementing bank specific regulatory requirements, and to allow full utilization of the capital and liquidity buffers that financial institutions have built. I am unclear on how much this will work in order to keep the flow of credit flowing, but overall, my sentiment is that on cheap and easy financing to banks and (hopefully) to firms, there is little more ECB could do.

- The second set of measure is a ramping up of QE, with additional €120bn (until the end of the year). Lagarde seemed to suggest that the ECB could use flexibility to deviating from capital keys, the quota of bonds the ECB can buy from each country. This means that maybe more help will be given to countries like Italy, and the ambiguity was probably on purpose.

But then came the Q&A, and with it, disaster. At a question by a journalist on Italian debt and yields, Lagarde replied the following:

This also made it on the ECB twitter feed:

This simple sentence was a reversal of Mario Draghi 2012 “whatever it takes“. Mario Draghi, in 2012, had basically announced that the ECB would act as a crypto-lender of last resort (conditional, way too conditional, but still), and since then the scope for speculation has been greatly reduced. Spreads have been much less variable since then (I wrote a paper with Roberto Tamborini, on that, that just came out).

Protection from the ECB against market speculation is what countries like Italy would need most. Fiscal policy is the tool that can be better targeted towards supporting the supply side of the economy and preventing liquidity problems from evolving into bankruptcies. Lagarde herself stated it many times in the past few days, and again today.

So, governments should be put in the conditions not to worry, at least for a while, of market pressure. Lagarde should have said the exact opposite: “we commit to freezing the spreads for n months so that governments can focus on supporting their productive sector, and restoring more or less normal aggregate demand conditons”. Lagarde said the opposite. And here is the effect of that on Italian ten year rates. Look what happened at around 3pm, when she answered the question:

The yields Other Eurozone peripheral countries had similar behaviours. Why did Lagarde say that? Maybe Because she wanted to appease fiscal hawks ahead of the Eurogroup meeting of next week, so that they are more willing to agree on a fiscal stimulus? Or because she was afraid to be accused to be too soft on Italy? Or to actually care about one single country, which is what the ECB is not supposed to do? Or was it simply a communication misstep? A rookie mistake? Whatever the reason, it is clear that Lagarde made a huge mistake, and even apparently she partially backpedaled in a NBC interview shortly thereafter, this is what remain of today’s press conference.

So, my assessment of today’s ECB move is mixed. It was as good as it gets on financing the banking sector, and we just have to cross finger that this is enough to keep credit flowing.

But it is disappointing on the support of expansionary fiscal policies. All the more disappointing that the ECB and Lagarde have insisted on the need for a fiscal response “first and foremost”.

My only hope is that that was a misstep, or just lip service to fiscal responsibility. If market pressure prevents governments from supporting their firms, and if liquidity problems evolve into solvency problems, a “significant but temporary” shock will become a permanent hit to long-term growth capacity. And let’s not forget that the Eurozone economy is today more diverse and less resilient than it was in 2008.

Brace yourself

ps. You can find my live tweeting during the Q&A (a bit confused at times. Live tweeting is not my thing!) here:

Monetary Policy: Credibility 2.0

Life and work keep having the nasty habit of intruding into this blog, but it feels nice to resume writing, even if just with a short comment.

We learned a few weeks ago that the Bank of Japan has walked one extra step in its attempt to escape lowflation, and that it has committed to overshoot its 2% inflation target. A “credible promise to be irresponsible”, as the FT says quoting Paul Krugman.

This may be a long overdue first step towards a revision of the inflation target, as invoked long ago by Olivier Blanchard, and more recently by Larry Ball. This is all too reasonable: if the equilibrium interest rates are negative, if monetary policy is bound by the zero-or-only-slightly-negative-lower-bound, higher inflation targets would make sense, and 4% is an arbitrary target as legitimate as the current also arbitrary 2% level. Things may be moving, as the subject was evoked, if not discussed, at the recent Central Bankers gathering in Jackson Hole. We’ll see if anything comes out of this.

But the FT also adds an interesting comment to the BoJ move, namely that the more serious risk is a blow to credibility. If it failed to lift the inflation to the 2% target, how can it be credibly believed to overshoot it?

This is a different sort of credibility issue, much more reasonable indeed, than the one we have been used to in the past three decades, linked to the concept of dynamic inconsistency. In plain English the idea that an actor has no incentive to keep prior commitments that go against its own interest, and hence deviates from the initial plan. Credibility was therefore associated to changing incentives over time (typically for policy makers), and invoked to recommend rules over discretion.

Today, eight years into the zero lower bound, we go back to a more intuitive definition of credibility: announcing an objective and not being able to attain it.

The difference between the two definitions of credibility is not anodyne. In the first case, the unwillingness of central banks to behave appropriately can be corrected through the adoption of constraining rules. In the latter, the central bank cannot attain the objective regardless of incentives and constraints, and other strategies need to be put in place.

The other strategy, the reader will not be surprised to learn, is fiscal policy. Monetary dominance is in fact a second tenet of the Consensus from the 1990s that the crisis has wiped out. We used to live in a world in which structural reforms would take care of increasing potential growth, monetary policy would be used to take care of (minor) demand-driven fluctuations, and fiscal policy was in a closet.

This is gone (luckily). Even the large policy making institutions now call for a comprehensive and multi-instrument policy making. The policy mix, a central element of macroeconomics in the pre-rational expectations era, is now back. Even the granitic dichotomy between short (demand driven) and long (supply driven) term, is somewhat rediscussed.

The excessively simplified consensus that dominated macroeconomics for the past thirty years seems to be seriously in trouble; complexity, tradeoffs, coordination, are now the issues discussed in academia and in policy circles. This is good news.

.

Pushing on a String

Readers of this blog know that I have been skeptical on the ECB quantitative easing program.

I said many times that the eurozone economy is in a liquidity trap, and that making credit cheaper and more abundant would not be a game changer. Better than nothing, (especially for its impact on the exchange rate, the untold objective of the ECB), but certainly not a game changer.

The reason, is quite obvious. No matter how cheap credit is, if there is no demand for it from consumers and firms, the huge liquidity injections of the ECB will end up inflating some asset bubble. Trying to boost economic activity (and inflation) with QE is tantamount to pushing on a string.

I also said many times that without robust expansionary fiscal policy, recovery will at best be modest.

Two very recent ECB surveys provide strong evidence in favour of the liquidity trap narrative. The first is the latest (April 2016) Eurozone Bank Lending Survey. Here is a quote from the press release:

The net easing of banks’ overall terms and conditions on new loans continued for loans to enterprises and intensified for housing loans and consumer credit, mainly driven by a further narrowing of loan margins.

So, nothing surprising here. QE and negative rates are making so expensive for financial institutions to hold liquidity, that credit conditions keep easing.

So why do we not see economic activity and inflation pick up? The answer is on the other side of the market, credit demand. And the Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises in the euro area, published this week also by the ECB, provides a clear and loud answer (from p. 10):

“Finding customers” was the dominant concern for euro area SMEs in this survey period, with 27% of euro area SMEs mentioning this as their main problem, up from 25% in the previous survey round. “Access to finance” was considered the least important concern (10%, down from 11%), after “Regulation”, “Competition” and “Cost of production” (all 14%) and “Availability of skilled labour” (17%). Among SMEs, access to finance was a more important problem for micro enterprises (12%). For large enterprises, “Finding customers” (28%) was reported as the dominant concern, followed by “Availability of skilled labour” (18%) and “Competition” (17%). “Access to finance” was mentioned less frequently as an important problem for large firms (7%, unchanged from the previous round)

No need to comment, right?

Just a final and quick remark, that in my opinion deserves to be developed further: finding skilled labour seems to become harder in European countries. What if these were the first signs of a deterioration of our stock of “human capital” (horrible expression), after eight years of crisis that have reduced training, skill building, etc.?

When sooner or later the crisis will really be over, it will be worth keeping an eye on “Availability of skilled labour” for quite some time.

Tell me again that story about structural reforms enhancing potential growth?

Whatever it Takes Cannot be in Frankfurt

Yesterday I was asked by the Italian weekly pagina99 to write a comment on the latest ECB announcement. Here is a slightly expanded English version.

Mario Draghi had no choice. The increasingly precarious macroeconomic situation, deflation that stubbornly persists, and financial markets that happily cruise from one nervous breakdown to another, had cornered the ECB. It could not, it simply could not, risk to fall short of expectations as it had happened last December. And markets have not been disappointed. The ECB stored the bazooka and pulled out of the atomic bomb. At the press conference Mario Draghi announced 6 sets of measures (I copy and paste):

- The interest rate on the main refinancing operations of the Eurosystem will be decreased by 5 basis points to 0.00%, starting from the operation to be settled on 16 March 2016.

- The interest rate on the marginal lending facility will be decreased by 5 basis points to 0.25%, with effect from 16 March 2016.

- The interest rate on the deposit facility will be decreased by 10 basis points to -0.40%, with effect from 16 March 2016.

- The monthly purchases under the asset purchase programme will be expanded to €80 billion starting in April.

- Investment grade euro-denominated bonds issued by non-bank corporations established in the euro area will be included in the list of assets that are eligible for regular purchases.

- A new series of four targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO II), each with a maturity of four years, will be launched, starting in June 2016. Borrowing conditions in these operations can be as low as the interest rate on the deposit facility.

Items 1-3 depict a further decrease of interest rates. Answering a question Mario Draghi hinted that rates will be lower for a long period, but also that this may be the lower bound (sending markets in an immediate tailspin; talk of rational, well thought decisions). The “tax” the ECB imposes on excess reserves, the liquidity that financial institutions keep idle, is now at -0,4%. Not insignificant.

But the real game changer are the subsequent items, that really represent an innovation. Items 4-5 announce an acceleration of the bond buying program, and more importantly its extension to non-financial corporations, which changes its very nature. In fact, the purchase of non-financial corporations’ securities makes the ECB a direct provider of funding for the real sector. With these quasi-fiscal operations the ECB has therefore taken a step towards what economists call “helicopter money”, i.e. the direct financing of the economy cutting the middlemen of the financial and banking sector.

Finally, item 6, a new series of long-term loan programs, with the important innovation that financial institutions which lend the money to the real sector will obtain negative rates, i.e. a subsidy. This measure is intended to lift the burden for banks of the negative rates on reserves, at the same time forcing them to grant credit: The banks will be “paid” to borrow, and then will make a profit as long as they place the money in government bonds or lend to the private sector, even at zero interest rates.

To summarize, it is impossible for the ECB to do more to push financial institutions to increase the supply of credit. Unfortunately, however, this does not mean that credit will increase and the economy rebound. There is debate among economists about why quantitative easing has not worked so far. I am among those who think that the anemic eurozone credit market can be explained both by insufficient demand and supply. If credit supply increases, but it is not followed by demand, then today’s atomic bomb will evolve into a water gun. With the added complication that financial institutions that fail to lend, will be forced to pay a fee on excess reserves.

But maybe, this “swim or sink” situation is the most positive aspect of yesterday’s announcement. If the new measures will prove to be ineffective like the ones that preceded them, it will be clear, once and for all, that monetary policy can not get us out of the doldrums, thus depriving governments (and the European institutions) of their alibi. It will be clear that only a large and coordinated fiscal stimulus can revive the European economy. Only time will tell whether the ECB has the atomic bomb or the water gun (I am afraid I know where I would place my bet). In the meantime, the malicious reader could have fun calculating: (a) How many months of QE would be needed to cover the euro 350 billion Juncker Plan, that painfully saw the light after eight years of crisis, and that, predictably, is even more painfully being implemented. (b) How many hours of QE would be needed to cover the 700 million euros that the EU, also very painfully, agreed to give Greece, to deal with the refugee influx.

And the Winner is (should be)…. Fiscal Policy!

So, Mario Draghi is disappointed by eurozone growth, and is ready to step up the ECB quantitative easing program. The monetary expansion apparently is not working out as planned.

Big surprise. I am afraid some people do not have access to Wikipedia. If they had, they would read, under “liquidity trap“, the following:

A liquidity trap is a situation, described in Keynesian economics, in which injections of cash into the private banking system by a central bank fail to decrease interest rates and hence make monetary policy ineffective. A liquidity trap is caused when people hoard cash because they expect an adverse event such as deflation, insufficient aggregate demand, or war.

In a liquidity trap the propensity to hoard of the private sector becomes virtually unlimited, so that monetary policy (be it conventional or unconventional) loses traction. It is true that the age of great moderation, and three decades of almighty central bankers had made the concept fade into oblivion. But, since 2008 we were forced to reconsider the effectiveness of monetary policy at the so-called zero lower bound.Or at least we should have…

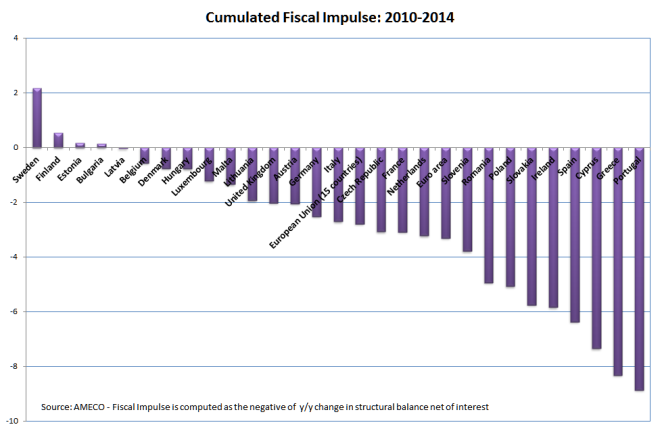

So, had policy makers taken the time to look at the history of the great depression, or at least to open the Wikipedia entry, they should have learnt that when monetary policy loses traction, the witness in lifting the economy out of the recession, needs to be taken by fiscal policy. In a liquidity trap the winner is fiscal policy. Or at least it should be. Here is a measure of the fiscal stance, computed as the change in government balance once we exclude cyclical components and interest payments.

The vast majority of E

The vast majority of EMU countries undertook a strong fiscal tightening, regardless of the actual health of their public finances. This generalized austerity, an offspring of the Berlin View, led to our double dip recession, and to further divergence in the eurozone, that would have needed coordinated, not synchronized fiscal policies. Well done guys…

And yet, Mario Draghi is surprised by the impact of QE.

Raise Fed Rates Now?

A quick note on the US and the Fed. Pressure for rate rises never really stopped, but lately it has intensified. Today I read on the FT that James Bullard, Saint Louis Fed head, urges Janet Yellen to raise rates as soon as possible, to avoid “devastating asset bubbles”. Just a few months ago we learned that QE was dangerous because, once again through asset price inflation, it led to increasing inequality. Not to mention the inflationistas (thanks PK for the great name!) who since 2009 have been predicting Weimar-type inflation because of irresponsible Fed behaviour (a very similar pattern can be found in the EMU). Let’s play the game, for the sake of argument. After all, asset price inflation, and distortions in general are not unlikely in the current environment. So let’s assume that the Fed suddenly were convinced by its critics, and turned its policy stance to restrictive (hopefully this is just a thought experiment). I have two related questions to rate-raisers (the same two questions apply to QE opponents in the EMU):

- Do they think that private expenditure is healthy enough to grow and to sustain economic activity without the oxygen tent of monetary policy?

- If not, would they be willing to accept that monetary restriction is accompanied by a fiscal expansion?

I am afraid we all know the answer, at least to the second of these questions. Just yesterday, on Italian daily Il Corriere della Sera, Alberto Alesina and Francesco Giavazzi called for public expenditure cuts, invoking the confidence fairy and expansionary austerity (yes, you have read well. Check for yourself if you understand Italian. And check the date, it is 2015, not 2007) What Fed (and ECB) bashers tend to forget, in conclusion, is that central bankers are at the center of the stage, reluctantly, because they have to fill the void left, for different reasons, by fiscal policy. Look at the fiscal stance for the US:  Fiscal impulse, the discretionary stance of the US government, was positive only in 2008-2009, and has been restrictive since then. In other words, while the US were experiencing the worse crisis since the 1930s, while recovery was sluggish and jobless, the US government was pushing the brake. We all know why: political blockage and systematic boycott, by one side of Congress, of each and every one of the measures proposed by the administration (that was a bit too timid, if I may say so). Whatever the reasons, the fact remains that fiscal policy was of very limited help during the crisis. What do Fed bashers have to say about this? What would have happened if, faced with procyclical fiscal policy, the Fed had not stepped in with QE? I am afraid their answer would once again turn around confidence fairies… The EMU is pretty much in the same situation. The following figure shows the cumulative fiscal impulse since 2008 for a number of countries:

Fiscal impulse, the discretionary stance of the US government, was positive only in 2008-2009, and has been restrictive since then. In other words, while the US were experiencing the worse crisis since the 1930s, while recovery was sluggish and jobless, the US government was pushing the brake. We all know why: political blockage and systematic boycott, by one side of Congress, of each and every one of the measures proposed by the administration (that was a bit too timid, if I may say so). Whatever the reasons, the fact remains that fiscal policy was of very limited help during the crisis. What do Fed bashers have to say about this? What would have happened if, faced with procyclical fiscal policy, the Fed had not stepped in with QE? I am afraid their answer would once again turn around confidence fairies… The EMU is pretty much in the same situation. The following figure shows the cumulative fiscal impulse since 2008 for a number of countries:  The figure speaks for itself. With the exception of Japan (thanks Abenomics!) governments overall acted as brakes for the economy (Alesina and Giavazzi should look at the data for Italy, by the way). Central banks had to act in the thunderous silence of fiscal policy. So I repeat my question once again: who would be willing to exchange a normalization of monetary policy with a radical change in the fiscal stance? To conclude, yes, monetary policy has been very proactive (even Mario Draghi’s ECB); yes, this led us in unchartered lands, and we do not fully grasp what will be the long term effects of QEs and unconventional monetary policies; yes, some distortions are potentially dangerous. But central bankers had no choice. We are in a liquidity trap, and the main tool to be used should be fiscal policy. Monetary policy could and should be normalized, if only fiscal policy would finally take the witness, and the burden to lift the economy out of its woes; if fiscal policy finally tackled the increasing inequality that is choking the economy. If fiscal policy did its job, in other words.

The figure speaks for itself. With the exception of Japan (thanks Abenomics!) governments overall acted as brakes for the economy (Alesina and Giavazzi should look at the data for Italy, by the way). Central banks had to act in the thunderous silence of fiscal policy. So I repeat my question once again: who would be willing to exchange a normalization of monetary policy with a radical change in the fiscal stance? To conclude, yes, monetary policy has been very proactive (even Mario Draghi’s ECB); yes, this led us in unchartered lands, and we do not fully grasp what will be the long term effects of QEs and unconventional monetary policies; yes, some distortions are potentially dangerous. But central bankers had no choice. We are in a liquidity trap, and the main tool to be used should be fiscal policy. Monetary policy could and should be normalized, if only fiscal policy would finally take the witness, and the burden to lift the economy out of its woes; if fiscal policy finally tackled the increasing inequality that is choking the economy. If fiscal policy did its job, in other words.

I don’t know why, but I have the feeling that Janet Yellen and Mario Draghi would not completely disagree.

Confidence and the Bazooka

It seems that we finally have our Bazooka. Quantitative Easing will be put in place; its size is slightly larger than expected (€60bn a month), and Mario Draghi, once again, seems to have gotten what he wanted in his confrontation with hawks within and outside the ECB (I won’t comment on risk sharing. I am far from clear about the consequences of that).

And yet, something is just not right. I am afraid that QE will end up like LTRO and all the other liquidity injections the ECB performed in the past. What bothers me is not the shape of the program (given the political constraints, one could hardly imagine something more radical), but Draghi’s press conference. Here is a quote from the introductory statement:

Monetary policy is focused on maintaining price stability over the medium term and its accommodative stance contributes to supporting economic activity. However, in order to increase investment activity, boost job creation and raise productivity growth, other policy areas need to contribute decisively. In particular, the determined implementation of product and labour market reforms as well as actions to improve the business environment for firms needs to gain momentum in several countries. It is crucial that structural reforms be implemented swiftly, credibly and effectively as this will not only increase the future sustainable growth of the euro area, but will also raise expectations of higher incomes and encourage firms to increase investment today and bring forward the economic recovery. Fiscal policies should support the economic recovery, while ensuring debt sustainability in compliance with the Stability and Growth Pact, which remains the anchor for confidence. All countries should use the available scope for a more growth-friendly composition of fiscal policies.

And here the answer to a question, even more explicit:

What monetary policy can do is to create the basis for growth, but for growth to pick up, you need investment. For investment you need confidence, and for confidence you need structural reforms. The ECB has taken a further, very expansionary measure today, but it’s now up to the governments to implement these structural reforms, and the more they do, the more effective will be our monetary policy. That’s absolutely essential, as well as the fiscal consolidation side. So structural reforms is one thing, budget and fiscal consolidation is a different issue. It’s very important to have in place a so-called growth-friendly fiscal consolidation for confidence strengthening. This combined with a monetary policy which is very expansionary, which has been and is even more so after our decisions today, is actually the optimal combination. But for this now, we need the actions by the governments, and we need the action also by the Commission, both in its overseeing role of fiscal policies and in its implementing the investment plan, which was launched by the President of the Commission, which was certainly welcome at the time, now has to be implemented with speed. Speed is of the essence.

The message could not be any clearer: Draghi expects the QE program to impact economic activity through private spending. What we have here is the nt-th comeback of the confidence fairy: accommodative monetary policy, structural reforms and fiscal consolidation, will cause a private expenditure surge (“[..] but will also raise expectations of higher incomes and encourage firms to increase investment today and bring forward the economic recovery“). We have been told this many times since 2010.

Unfortunately, it did not work like this, and I am afraid it will not this time either. The private sector signals in all surveys available that it is not ready to resume spending. If governments are not given the possibility to spend more, most of the liquidity injected into the system will remain idle, exactly as it was the case for the (T)LTRO.

The concept of countercyclical policies is so trivial as to become commonsensical: Governments should step in when markets step out, and withdraw when markets step in again. Filling the gap will actually sustain economic activity, and crowd-in private expenditure; more so, much more so, than filling the pockets of agents with money they are not willing to spend. This is the essence of Keynes. Since 2010 in Europe governments rushed to the exit together with markets; joint deleveraging meant depressed economy. How could one be surprised that confidence does not return?

I would like to add that invoking more active fiscal policy within the limits of the Treaties has the flavour of a bad joke. Just so as we understand what we are talking about, the EMU 18 in 2014 had a deficit-to-GDP ratio of 2.6% (preliminary estimates by the Commission, Ameco database); this means that to remain within the Treaty a fiscal stimulus would have to be limited to 0.4% of GDP. How large would the multiplier have to be, for this to lift the eurozone economy out of deflation? Even the most ardent Keynesian would have a hard time claiming that!! And also, so as we don’t forget, at less than 95% of GDP EMU, Gross public debt can hardly be seen as an obstacle to a serious fiscal stimulus. Even in the short run.

The point I want to make is that QE is all very good, but European governments need to be put in condition to spend the money. It is tiring to repeat the same thing again and again: in a liquidity trap monetary policy can only be a companion to the main tool that could be used by policy makers: fiscal policy.

But in Europe, bad economic policy is today considered a virtue.

ECB: One Size Fits None

Eurostat just released its flash estimate for inflation in the Eurozone: 0.5% headline, and 0.8% core. We now await comments from ECB officials, ahead of next Thursday’s meeting, saying that everything is under control.

Just this morning, Wolfgang Münchau in the Financial Times rightly said that EU central bankers should talk less and act more. Münchau also argues that quantitative easing is the only option. A bold one, I would add in light of todays’ deflation inflation data. Just a few months ago, in September 2013, Bruegel estimated the ECB interest rate to be broadly in line with Eurozone average macroeconomic conditions (though, interestingly, they also highlighted that it was unfit to most countries taken individually).

In just a few months, things changed drastically. While unemployment remained more or less constant since last July, inflation kept decelerating until today’s very worrisome levels. I very quickly extended the Bruegel exercise to encompass the latest data (they stopped at July 2013). I computed the target rate as they do as

.

(if you don’t like the choice of parameters, go ask the Bruegel guys. I have no problem with these). The computation gives the following:

Using headline inflation, as the ECB often claims to be doing, would of course give even lower target rates. As official data on unemployment stop at January 2014, the two last points are computed with alternative hypotheses of unemployment: either at its January rate (12.6%) or at the average 2013 rate (12%). But these are just details…

So, in addition to being unfit for individual countries, the ECB stance is now unfit to the Eurozone as a whole. And of course, a negative target rate can only mean, as Münchau forcefully argues, that the ECB needs to get its act together and put together a credible and significant quantitative easing program.

Two more remarks:

- A minor one (back of the envelope) remark is that given a core inflation level of 0.8%, the current ECB rate of 0.25%, is compatible with an unemployment gap of 1.95%. Meaning that the current ECB rate would be appropriate if natural/structural unemployment was 10.65% (for the calculation above I took the value of 9.1% from the OECD), or if current unemployment was 11.5%.

- The second, somewhat related but more important to my sense, is that it is hard to accept as “natural” an unemployment rate of 9-10%. If the target unemployment rate were at 6-7%, everything we read and discuss on the ECB excessively restrictive stance would be significantly more appropriate. And if the problem is too low potential growth, well then let’s find a way to increase it…