Archive

A Plea for a European Public Investment Agency

The European Commission has introduced a legislative proposal for the reform of European fiscal rules with the aim to have the new rules approved by member states and the European Parliament by the end of the year, and to be in force by 2024. If this timeline is not met, the old Stability and (lack of) Growth Pact (SGP), adopted in 1997 and discredited during the sovereign debt crisis, will be reintroduced.

The Stability Pact, together with the Fiscal Compact hastily adopted in 2012 in the belief (oh, how erroneous! ) that it was necessary to impose austerity in order to get out of the sovereign debt crisis, impose annual targets in terms of structural (i.e. cyclically-adjusted) deficit to ensure that public debt falls steadily towards the level of 60% set by the Maastricht Treaty (a level that is totally arbitrary, incidentally). From the outset, many of us criticised the Stability Pact, because the emphasis on annual targets pushes countries to adopt pro-cyclical policies: in the event of a crisis and a fall in GDP, to stay on the path of debt reduction, fiscal restraint is needed; this has nevertheless a negative impact on growth, triggering a vicious circle. Moreover, the Pact imposes the same objectives on everyone (one size fits all is used). Last but not least, the current rule does not distinguish between current expenditure and investment spending, ending up penalizing the latter which, politically, is less problematic to cut.

To address these issues, the European Commission reform proposal replaces annual targets with multi-year debt reduction programs agreed upon by member countries and the Commission. Although very imperfect, the proposal represents a very clear improvement on the existing rule, on two grounds..

- The annual numerical targets are replaced by multi-annual (4-year) debt reduction programs. The adoption of a medium-term perspective, is the only reasonable one when it comes to the sustainability of public finances. It is good that we have finally realised the absurdity of annual targets

- Debt-reduction plans are formulated (in terms of expenditure targets) by member countries in agreement with the Commission, on the basis of scenarios for the evolution of public finances. High-debt countries obviously need to make greater efforts, especially if the most likely scenarios are high interest rates and low growth, and therefore more risks to future sustainability. Abandoning the one-size-fits-all and top-down approach is important for democratic legitimacy and credibility of implementation.

Against these very significant improvements, the amended rule would remain seriously problematic for two reasons. The first is that overall the focus is still on debt reduction. Too much Stability and not enough growth, like with the old SGP, at the risk of obtaining neither (ever heard of self-defeating austerity?) This is even trues since, to accommodate strong German pressures the Commission has introduced safeguards to ensure that debt remains strongly anchored to a downward path. This excessive weight on debt reduction might be tempered by the increased politicization of the process, a feature of the Commission proposal that has been criticized but that on the contrary I find quite appealing. I will come back to that in a future post.

The second reason why the Commission proposal (a significant improvement, let me state it again) falls short of my expectations is the lack of specific provisions for protecting public investment. The only concession that is made is that “Member States will benefit from a more gradual fiscal adjustment path if they commit in their plans to a set of reforms and investment that comply with specific and transparent criteria”. This is what I would like to address in this post.

With my colleagues Floriana Cerniglia (Catholic University Milano) and Andy Watt (IMK Berlin), we have been editors for some years of a series of yearly European Public Investment Outlook involving dozens of European researchers. Volume after volume, the message that comes out of this series is that in OECD countries public investment has been sacrificed on the altar of fiscal discipline since the 1980s. In Europe the downward trend is particularly marked and has further accelerated with the austerity programs of the 2010s. The result is a chronic shortage of public capital, both tangible and intangible (social capital) which today seriously limits the growth potantial of all European countries, even those that are apparently healthier. As an example, the German colleagues who worked on the chapters on Germany estimated the amount needed over the next decade to fill the German infrastructure gap at around 45 billion per year, not to mention the additional investment needs made necessary by an aging population and by the ecological and digital transition. Italy is no exception: Cerniglia and her co-authors report an estimate by which between 2008 and 2018 about 200 billion were lost along the way compared to the scenario in which public investment had continued at the (not excellent) previous rates. This figure is sobering: the entire allocation of the Italian NRRP (191 billion), which should project us into the ecological and digital transition, will not even be able to bridge the gap that has opened up in the last ten years.

Looking ahead, the numbers get even more impressive. The Commission has estimated that the European Union would need €520 billion in additional investment each year to meet the Green Deal’s 55% emissions cut target before the end of the decade. Although the Commission believes that a significant part of this investment should come from the private sector, the figure gives a measure of the colossal effort that lies before us.

A team from the New Economics Foundation (NEF), took the figure given by the Commission as a basis for simulations in which it also considered the needs related to social investment (education, health, etc.) and the digital transition. These simulations lead, in a report also published last week, to conclude that only nine European countries would have the fiscal space to implement such large investment programs, were they to respect the existing rule or even the one amended by the Commission proposal. Italy is obviously not one of them, but neither are France nor Germany. The assumption of the NEF report may be questioned, of course, but the overall picture they draw is quite clear, and highlights a fundamental incompatibility between the huge investment needs of the coming years and a system of European rules that, even in the reformed version, remain too oriented towards debt reduction as a self standing objective. The intransigent position of the German government has even prompted a usually cautious and moderate economist like Olivier Blanchard, former chief economist of the IMF, to ask rhetorically whether it is preferable to preserve the earth with a slightly higher debt or to go towards climate catastrophe with sound public finances

Many, including myself have for years called for a reform of European rules that would allow governments to invest outside the constraints of the budget. Such a “golden rule” would make it possible to finance the ecological transition while preserving the stability of public finances. In the past year it has at times seemed that such a proposal might have a chance of being discussed. Today the mood has changed. We should consider ourselves lucky if the Commission’s proposal is not twisted in an even more restrictive way by the negotiations with the Member States. In the coming years, therefore, it will be necessary to accept a continued state of chronically insufficient national public investment.

What to do then? If we do not want to fail in the objective of ecological transition, there is only one way: to work on the quick creation of a European Investment Agency able not only to finance national governments’ investment (as in the proposal for a Sovereign Fund for Industrial Policy, buried in the Brussels’ mist); but also to design and implement genuinely European investment projects. The governance of such an Agency should be designed very carefully: fiscal policy has an inherently political dimension that requires accountability in front of voters. In our non federal system this accountability lies with national governments, which should therefore be involved in European public investment choices. Some form of control by the Parliament and the Council in determining (or at least validating) investment projects would certainly make the work of the European Investment Agency more cumbersome. But this seems inevitable to ensure the democratic legitimacy of spending programmes (and their financing) at the European level.

Zombie Arguments Against Fiscal Stimulus

Busy days. I just want to drop a quick note on a piece just published on the Financial Times that is puzzling on many levels. Ruchir Sharma pleads against Joe Biden’s stimulus on the ground that it risks “exacerbating inequality and low productivity growth”. The bulk of the argument is in this paragraph:

Mr Biden captured this elite view perfectly when he said, in announcing his spending plan: “With interest rates at historic lows, we cannot afford inaction.”

This view overlooks the corrosive effects that ever higher deficits and debt have already had on the global economy. These effects, unlike roaring inflation or the dollar’s demise, are not speculative warnings of a future crisis. There is increasing evidence, from the Bank for International Settlements, the OECD and Wall Street that four straight decades of growing government intervention in the economy have led to slowing productivity growth — shrinking the overall pie — and rising wealth inequality.

If one reads the two papers cited by Sharma, they say, in a nutshell, (a) that expansionary monetary policies have deepened income inequality via an increase in asset prices (while for low interest rates and bond prices there is no clear link); (b) that the increasing share of zombie firms drags down the performance of more productive firms thus slowing down overall productivity growth.

So far so good. So where is the problem? Linking these results to excessive debt and deficit, to the “constant stimulus”, is stretched (and I am being kind). A clear case of Zombie Economics.

Let’s start with monetary policy and its impact on inequality (side note: the effect is not so clear-cut). One may see expansionary monetary policies as the consequence of fiscal dominance, excessive deficit and debt that force central banks to finance the government. But, they can also be seen as the consequence of stagnant aggregate demand that is not properly addressed by excessively restrictive fiscal policies, forcing central banks to step in. Many have argued in the past decade that especially in the Eurozone one of the causes of central bank activism was the inertia of fiscal policies. Don’t take my word. Read former ECB President Mario Draghi’s Farewell speech, in October 2019:

Today, we are in a situation where low interest rates are not delivering the same degree of stimulus as in the past, because the rate of return on investment in the economy has fallen. Monetary policy can still achieve its objective, but it can do so faster and with fewer side effects if fiscal policies are aligned with it. This is why, since 2014, the ECB has gradually placed more emphasis on the macroeconomic policy mix in the euro area.

A more active fiscal policy in the euro area would make it possible to adjust our policies more quickly and lead to higher interest rates.

This is as straightforward as a central banker can be: in order to go back to standard monetary policy making, fiscal policy needs to step up its game. Notice that Draghi also hints to another source of problems: the causality does not go from expansionary policies to low interest rates, but the other way round. We have been living in a a long period of secular stagnation, excess savings, low interest rates and chronic demand deficiency which monetary policy expansion can accommodate by keeping its rates close to “the natural” rate, but not address. Once again, fiscal policy should do the job.

Regarding zombie firms, it is unclear, barring the current and very special situation created by the pandemics, why this would prove that stimulus is unwarranted. The paper describes a secular trend whose roots are in insufficient business investment and a drop in potential growth rate (that in turn the authors link to a drop in multi-factor productivity). The debate on the role of fiscal policy in these matters is as old as macroeconomics. In the past ten years, nevertheless, the cursor has moved against the Sharma’s priors and an increasing body of literature points to crowding-in effects: especially when the stock of public capital is too low (as is the case in most advanced countries), an increase of public investment — “constant stimulus”– has a positive impact on private investment and potential growth (see for reference the most recent IMF fiscal monitor and the chapter by EIB economists of the European Public Investment Outlook). Lack of public investment is also widely believed to be one of the factors keeping our economies stuck in secular stagnation.

Fifteen years ago one could have read Sharma’s case against fiscal policy on many (more or less prestigious) outlets. Even then, it would have been easy to argue that it was flawed and fundamentally built on an ideological prior. Today, it seems simply written by somebody living in another galaxy.

A Plea for Semi-Permanent Government Deficits

Update (1/7/2016): The whole paper is now available on Repec.

I have recently written a text on EMU governance and the implementation of a Golden Rule of public finances. I will provide the link as soon as it comes out. The last section of that paper can be read stand alone (with some editing). A bit long, I warn you, but here it is:

Because of its depth, and of its length, the crisis has triggered an interesting discussion among economists about whether the advanced economies will eventually return to the growth rates they experienced in the second half of the twentieth century.

One view, put forward by Robert Gordon focuses on supply-side factors. Gordon argues that each successive technological revolution has lower potential impact, and that in this particular moment, “Slower growth in potential output from the supply side, emanating not just from slow productivity growth but from slower population growth and declining labor-force participation, reduces the need for capital formation, and this in turn subtracts from aggregate demand and reinforces the decline in productivity growth.”

In a famous speech at the IMF in 2013, later developed in a number of other contributions, Larry Summers revived a term from the 1930s, “secular stagnation”, to describe a dilemma facing advanced economies. Summers develops some of Gordon’s arguments to argue that lower technical progress, slower population growth, the drifting of firms away from debt-financed investment, all contributed to shifting the investment schedule to the left. At the same time, the debt hangover, accumulation of reserves (public and private) induced by financial instability, increasing income inequality (on that, I came first!), tend to push the savings schedule to the right. The resulting natural interest rate is close to zero if not outright negative, thus leading to a structural excess of savings over investment.

Summers argues that most of the factors exerting a downward pressure on the natural interest rate are not cyclical but structural, so that the current situation of excess savings is bound to persist in the medium-to-long run, and the natural interest rate may remain negative even after the current cyclical downturn. The conclusion is not particularly reassuring, as policy makers in the next several years will have to navigate between the Scylla of accepting permanent excess savings and low growth (insufficient to dent unemployment), and the and Charybdis of trying to fight secular stagnation by fuelling bubbles that eliminate excess savings, at the price of increased instability and risks of violent financial crises like the one we recently experienced.

The former IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard has elaborated on the meaning of Summers’ conjecture for macroeconomic policy. If interest rates will remain at (or close to) zero even once the crisis will be over, monetary policy will continuously face the Scylla and Charybdis. The recent crisis is a good case study of this dilemma, with the two major central banks of the world under fire from some quarters, for opposiite reasons: the Fed for having kept interest rates too low, contributing to the housing bubble and the ECB for having done too little and too late during the Eurozone crisis.

Drifting away from the Consensus that he contributed to consolidate, Blanchard concludes that exclusive reliance on monetary policy for macroeconomic stabilization should be reassessed. With low interest rates that make debt sustainability a non-issue; with financial markets deregulation that risks yielding more variance in GDP and economic activity; and with monetary policy (almost) constantly at the Zero Lower Bound, fiscal policy should regain a prominent role among the instruments for macroeconomic regulation, beyond the cycle. This is a very important methodological advance.

Nevertheless, in his plea for fiscal policy, Blanchard falls short of a conclusion that naturally stems from his own reading of secular stagnation: If the economy is bound to remain stuck in a semi-permanent situation of excessive savings, and if monetary policy is incapable of reabsorbing the imbalance, then a new role for fiscal policy may appear, that goes beyond the short-term stabilization that Blanchard (and Summers) envision. In fact, there are two ways to avoid that the ex ante excess savings results in a depressed economy: either one runs semi-permanent negative external savings (i.e. a current account surplus), or one runs semi-permanent government negative savings. The first option, the export-led growth model that Germany is succeeding to generalize at the EMU level, is not viable, except for an individual country implementing non cooperative strategies, because aggregate current account balances need to be zero. The second option, a semi-permanent government deficit, needs to be further investigated, especially in its implication for EMU macroeconomic governance

There are a number of ways, not necessarily politically feasible, to allow EMU countries to run semi-permanent government deficits. A first one could be to restore complete national budget sovereignty, (scrapping the Stability Pact). This would mean relying on market discipline alone for maintaining fiscal responsibility. As an alternative, at the opposite side of the spectrum, countries could create a federal expenditure capacity (which would imply the creation of an EMU finance minister with capacity to spend, the issuance of Eurobonds, etc.). Such an option is as unrealistic as the previous one. In an ideal world, the crisis and deflation would be dealt with by means of a vast European investment program, financed by the European budget and through Eurobonds. Infrastructures, green growth, the digital economy, are just some of the areas for which the optimal scale of investment is European, and for which a long-term coordinated plan would necessary. The increasing mistrust among European countries exhausted by the crisis, and the fierce opposition of Germany and other northern countries to any hypothesis of debt mutualisation, make this strategy virtually impossible. The solution must therefore be found at national level, without giving up European-wide coordination, which would guarantee effective and fiscally sustainable investment programs.

In general, the multiplier associated with public investment is larger than the overall expenditure multiplier. This is particularly true in times of crisis, when the economy is, like today, at the zero lower bound. With Kemal Dervis I proposed that the EMU adopts a fiscal rule similar to the one implemented in the UK by Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown in the 1990s, and applied until 2009. The new rule would require countries to balance their current budget, while financing public capital accumulation with debt. Investment expenditure, in other words, would be excluded from deficit calculation, a principle that timidly emerges also in the Juncker plan. Such a rule would stabilize the ratio of debt to GDP, it would focus efforts of public consolidation on less productive items of public spending, and would ensure intergenerational equity (future generations would be called to partially finance the stock of public capital bequeathed to them). Last, but not least, especially in the current situation, putting in place such a rule would not require treaty changes, and it is already discussed, albeit timidly, in EU policy circles.

To avoid the bias towards capital expenditure that the golden rule could trigger, we proposed that at regular intervals, for example in connection with the European budget negotiation, the Commission, the Council and the Parliament could find an agreement on the future priorities of the Union, and make a list of areas or expenditure items exempted from deficit calculation for the subsequent years.

John Maynard Trump?

A sentence from Donald Trump’s victory speech retained a good deal of attention:

We are going to fix our inner cities and rebuild our highways, bridges, tunnels, airports, schools, hospitals. We’re going to rebuild our infrastructure, which will become, by the way, second to none. And we will put millions of our people to work as we rebuild it.

This was widely quoted in the social media, together with the following from an FT article about the Fed:

In particular, some members of his economic advisory team are convinced that central banks such as the US Federal Reserve have exhausted their use of super-loose monetary policy. Instead, in the coming months they hope to announce a wave of measures such as infrastructure spending, tax reform and deregulation to boost growth — and combat years of economic stagnation.

In spite of its vagueness, the idea of an infrastructure push has sent markets to beyond the roof. In short, a simple (and rather generic) speech on election night has dispelled all the anxiety about the long phase of uncertainty that we face. So long for efficient markets…

But this is not what I care about here. The point I want to make is that Trump’s announcement has triggered a strange reaction. Something going like: “See? Trump managed to break the establishment’s hostility to Keynes and to finally implement the stimulus policies we need. Forget the sexism and the p-word, the attacks on minorities, the incompetence. Enter Trump, exit neo-liberalism”. I see this especially (but not only) among Italian internauts, who tend to project the European situation in other contexts.

Well, I have some reservations on this claim. Where to start? Maybe with the “Contract with the American Voter“, that together with the (generic, once more) promise of new investment, promised a massive withdrawal of the State from the economy? Or from the fact that “Establishment Obama” made Congress vote, a month into his presidency, a “Recovery Act (ARRA)” worth 7% of GDP, that successfully stopped the free-fall and helped restore growth? Or from the fact that the “anti-establishment” Tea Party forced austerity since 2011, climaxing in the sequester saga of 2013?

Critics of current austerity policies in Europe should not be delusional. Trump is not the John Maynard Keynes of 2016. His agenda is, broadly speaking, an agenda of deregulation, tax cuts for the rich, and retreat of the State from the economy. Not to mention the strong chance of a more hawkish Fed in the future. To sum up, Trump is, in the best case scenario a new Reagan, substituting military Keynesianism with bridges’ Keynesianism. And we all (should) know that Reaganomics does shine much less than usually claimed.

Those progressives looking for a Trump Keynesian agenda should probably have looked more carefully at the plan proposed by “establishment-Clinton”: A significant infrastructure push (in fact, the emphasis on infrastructures was the only point in common between the two candidates), with the ambition to crowd-in private investment. And what is more important, such an expansionary fiscal policy was framed within a more active role of the government in key sectors like education, health care, and with increased progressivity of the tax system.

Would we have had Hilary Rodham Keynes? Unfortunately we’ll never know…

Draghi Wants the Cake, and Eat It

Yesterday Mario Draghi has called once more for other policies to support the ECB titanic (and so far vain) effort to lift the eurozone economy out of its state of semi-permanent stagnation. Here is the exact quote from his introductory remarks at the European Parliament hearing:

In parallel, other policies should help to put the euro area economy on firmer grounds. It is becoming clearer and clearer that fiscal policies should support the economic recovery through public investment and lower taxation. In addition, the ongoing cyclical recovery should be supported by effective structural policies. In particular, actions to improve the business environment, including the provision of an adequate public infrastructure, are vital to increase productive investment, boost job creations and raise productivity. Compliance with the rules of the Stability and Growth Pact remains essential to maintain confidence in the fiscal framework.

In a sentence, less taxes, more public investment (in infrastructures), and respect of the 3% limit. I just have two very quick (related) comments:

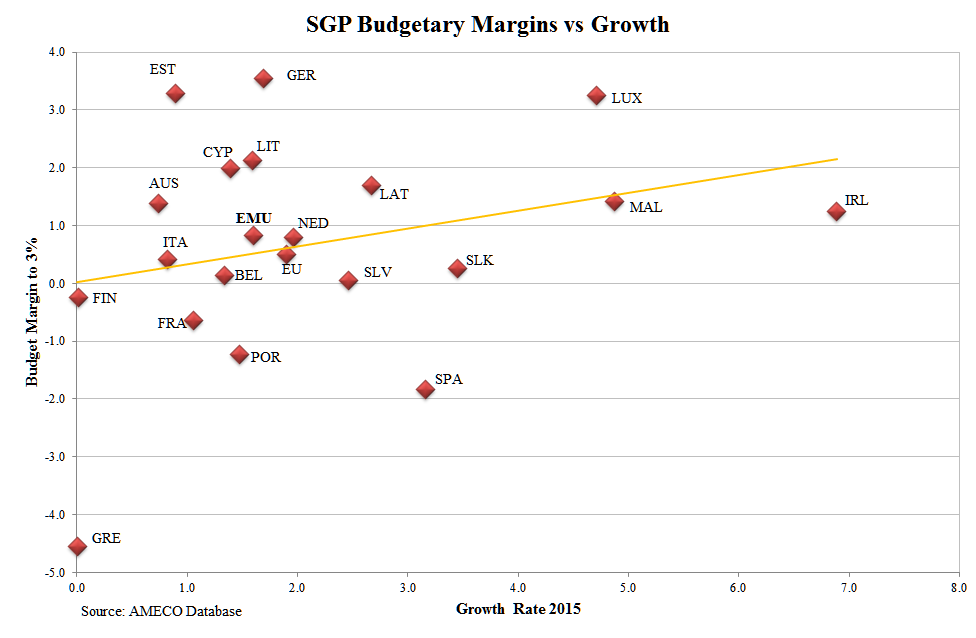

- Boosting growth remaining within the limits of the stability pact simply cannot happen. I just downloaded from the Commission database the deficit figures and the growth rate for 2015. And I computed the margin (difference between deficit and the 3% SGP limit). Here is what it gives:

Not only the margin for a fiscal expansion is ridiculously low for the EMU as a whole (at 0.8% of GDP, assuming a multiplier of 1.5 this would give globally 1.2% of extra growth). But it is also unevenly distributed. The (mild) positive slope of the yellow trend line, tells us that the countries that have a wider margin are those which need it the less as, overall, they grew faster in 2015. Said otherwise, we should ask the same guys who are unable to show a modicum of decency and solidarity in managing a humanitarian emergency like the refugee crisis, to coordinate in a fiscal expansion for the common good of the eurozone. Good luck with that…

Mr Draghi is too smart not to know that the needed fiscal expansion would require breaching the limits of the pact. Unless we had a real golden rule, excluding public investment from deficit computation. - So, how can we have lower taxes, more investment, and low deficit? The answer seems one, and only one. Cutting current expenditure. And I think it is worth being frank here: Besides cutting some waste at the margin, the only way to reduce current public expenditure is to seriously downsize our welfare state. We may debate whether our social model is incompatible with the modern globalized economy (I don’t think it is). But pretending that we can have the investment boost that even Mr Draghi today think is necessary, leaving our welfare state untouched, is simply nonsense. You can’t have the cake and eat it.

Therefore, what we should be talking about is our social contract. Do we want to keep it or not? Are we ready to pay the price for it? Are we aware of what the alternative of low social protection would imply? Are our institutions ready for a world in which automatic stabilization would play a significantly lesser role? If after considering these (and other) questions, the EU citizen decided, democratically, to abandon the current EU social model, I would not object to it. I would disagree, but I would not object. The problem is that this change is being implemented, bit by bit, without a real debate. I am no fan of conspiracy theories. But when reading Draghi yesterday, I could not avoid thinking of an old piece by Jean-Paul Fitoussi, arguing that European policy makers were pursuing an hidden agenda (I have discussed it already). The crisis weakened resistance and is making it easier to gradually dismantle the EU social model. The result is growing disaffection, that really surprises nobody but those who do not want to see it. An Italian politician from an other era famously said that to think the worst of someone is a sin, but usually you are spot on…

The End of German Hegemony. Really?

I was puzzled by Daniel Gros’ recent Project Syndicate piece, in which he claims that Germany’s dominance of the EMU may be coming to an end. Gros’ argument is based on two facts. The first is the slowing growth rate of Germany, that seems to be heading towards the pre-crisis “normal” of slow growth (Germany grew less than EMU average for most of the period 1999-2007). The second, more geo-political, is the lack of willingness (or of capacity) to manage, the crises that face the EU (in particular the refugees crisis).

Gros concludes that this loss of influence is dangerous, because Germany will not be able to resist the changes in policies that are pushed by peripheral countries and by the ECB. Of course, implicit in this statement, is Gros’ belief that these policies were necessary and useful.

I welcome the recognition that Germany has steered the EMU since the beginning of the crisis. Those of us talking about the Germanification of Europe have been decried until very recently. Yet, I do not share, not at all, Gros view.

True, Germany’s growth is slowing down. These are the risks of an export-led growth model: countries are not masters of their own fate. Germany stayed clear from the peripheral countries’ crisis (that it contributed to create) by turning to the US and to emerging economies as markets for its exports. But now that these countries are also having problems, the limits of jumping on other countries’ shoulders to grow, become evident. I am surprised by Gros’ surprise, as this was evident from the very beginning.

But here I do not want to reiterate my criticisms of the export-led model, starting from the fallacy of composition. Instead, I would like to challenge Gros’ argument that Germany influence is waning. I would say on the contrary that the Germanification of the eurozone is almost complete.

I took a few macroeconomic variables, and contrasted Germany with the remaining 11 EMU members. Let’s start with (missing) domestic demand, a defining characteristic of the export-led growth model:

Since 2007, the yellow line (EMU11) and the red line (Germany) converged, mostly because domestic demand in the rest of the EMU was reduced. This led of course to an increased reliance of the EMU as a whole on exports. The EMU as a whole had an overall balanced external position in 2007, while it has a substantial current account surplus today (the EMU12 went from 0.5% to 3.4 projected for 2016. Germany went from 7% to 7.7%). In other words, the EMU11 joined Germany on the shoulders of the rest of the world.

Austerity has of course much to be blamed for this compression of domestic demand: Just look at government balances (net of interest payments):

True, the difference between Germany and the rest of EMU is today larger than in 2007. But since Germany and the Troika took the driving seat in 2010, government balances of the EMU11 have been steadily converging to surplus, and they are not going to stop in the foreseeable horizon (the Commission forecasts go until 2016).

Finally, if we look at one of the main drivers of growth, investment, the picture is the same.

Be it private or public, the EMU11 Gross Fixed Capital Formation has been converging towards the (excessively low) German level (I did not draw the differences, not to clutter the figure).

And of course, there are labour costs, for which convergence to Germany was brutal, even if the latter, rather than EMU peripheral countries, were the outlier. To summarize, during the crisis the difference between Germany and the rest of the EMU was substantially reduced, and will continue to be in the next years:

The difference was reduced for all variables, except for government deficit. Self-defeating austerity slowed down the convergence. But private expenditure, in particular investment, more than compensated.

So, if I were Gros, I would not worry too much. The Germanification of Europe is well on its way. If Germany does not go to the EMU11 (it definitely does not!), the EMU11 keeps going to Germany.

But as I am not Gros, I worry a lot.

The Blanchard Touch

Yesterday I commented on the intriguing box in which the IMF staff challenges one of the tenets of the Washington consensus, the link between labour market reform and economic performance.

But the IMF is not new to these reassessments. In fact over the past three years research coming from the fund has increasingly challenged the orthodoxy that still shapes European policy making:

- First, there was the widely discussed mea culpa in the October 2012 World Economic Outlook, when the IMF staff basically disavowed their own previous estimates of the size of multipliers, and in doing so they certified that austerity could not, and would not work (of course this led EU leaders to immediately rush to do more of the same).

- Then, the Fund tackled the issue of income inequality, and broke another taboo, i.e. the dichotomy between fairness and efficiency. Turns out that unequal societies tend to perform less well, and IMF staff research reached the same conclusion. And once the gates opened, it did not stop. The paper by Berg and Ostry was widely read. Then we had Ball et al on the distributional effects of fiscal consolidation (surprise, it increases inequality). Another paper investigated the channels for this link, highlighting how consolidation leads to increased inequality mostly via unemployment. And just last week I assisted to a presentation by IMF economists showing how austerity and inequality are positively related with political instability.

- On labour markets, before yesterday’s box 3.5, the Fund had disseminated research linking increased inequality with the decline in unionization.

- Then, of course, the “public Investment is a free lunch” chapter three of the World Economic Outlook, in the fall 2014.

- In between, they demolished another building block of the Washington Consensus: free capital movements may sometimes be destabilizing…

These results are not surprising per se. All of these issues are highly controversial, so it is obvious that research does not find unequivocal support for a particular view. All the more so if that view, like the Washington Consensus, is pretty much an ideological construction. Yet, the fact that research coming from the center of the empire acknowledges that the world is complex, and interactions among agents goes well beyond the working of efficient markets, is in my opinion quite something.

What does this mass (yes, now it can be called a mass) of work tells us? Three things, I would say. First, fiscal policy is back. it really is. The Washington Consensus does not exist anymore, at least in Washington. Be it because the multipliers are large, or because it has an impact on income distribution (and on economic efficiency); or again because public investment boosts growth, fiscal policy has a role to play both in dampening business cycle fluctuations and in facilitating stable and balanced long term growth. The fact that a large institution like the IMF has lent its support to this revival of consideration for fiscal policy, makes me hope that discussions about macroeconomic policy will be less ideological, even once the crisis will have passed.

The second thing I learn is that the IMF research department proves to be populated of true researchers, who continuously challenge and test their own views, and are not afraid of u-turns if their own research dictates them. I am sure it has always been the case. What is different from the past is that now they have a chief economist who seems more interested in understanding where the world goes than in preaching a doctrine.

The third remark is more problematic. If I write a paper saying that austerity will not be costly because multipliers are 0.5, and 2 years later retract my previous statement and argue that austerity is in fact self defeating, the impact on the world is zero. If the IMF does the same, during the two years huge suffering will be needlessly inflicted to masses of people. This poses a problem, as research by definition may be falsified. In the past an institution like the IMF would never have admitted a mistake. And we certainly do not want to go back there. Today they do admit the mistakes, but the suffering remains. The only way out to this problem is that the “new” IMF should learn to be cautious in its policy prescriptions, and always remember that any policy recommendation is bound to be sooner or later proven inappropriate by new data and research. We don’t live in a black and white world. Adopting a more prudent stance in dictating policies would be wise (in Brussels as well, it goes without saying). And of course, the disconnect between the army and the general is also a problem.

Europe Needs a Real Industrial Policy

The Juncker Commission is now up and running, and it is beginning to give an idea of where it wants to go. Unfortunately not far enough. The two defining moments of the first few months are the Juncker plan, and the new guidelines on flexibility in applying the Stability and Growth Pact. Both focus on public investment.

Public investment deficiency is now chronic across the OECD, and particularly in the EU. Less visible and politically sensible than current expenditure, for twenty years it has been the adjustment variable for European governments seeking to meet the Maastricht criteria, and to control their deficit. Since the crisis hit, private investment also collapsed, and it is still kept well below its long term trend by depressed demand and negative expectations.

Let’s start from the most recent Commission measure. The guidelines issued last weeks, that some countries trumpeted as a great victory against austerity, are in fact just a marginal change. The Commission only conceded that the structural effort towards the 60% debt-to-GDP ratio be relaxed for countries growing below potential, while reaffirming that in no circumstance, the 3% deficit limit should be breached, and that any extra investment needs to be compensated by expenditure reduction in the medium term1.

The Juncker plan foresees the creation of an Investment Fund endowed with €21bn from the European budget and from the European Investment Bank. This is meant to lever conspicuous private funds (in a ratio of 15 to 1) to attain €315bn, mobilized in three years. EU countries may chip into the Fund, but this is not compulsory, and the incentives to contribute are unclear: while the contribution to the fund would not be accounted as deficit (the guidelines confirm it), the allocation of investment will not be proportional to countries’ contributions.

Two aspects of the plan raise issues. First, it is hard to see how it will be possible for the newly established fund to raise the announced amount. The expected leverage ratio is very ambitious (some have described the plan as a huge subprime scheme). Second, even assuming that the plan could create a positive dynamics and mobilize private resources to the announced 315 billions, this amounts to just over 2% of GDP for the next three years (approximately 0.7% annually). In comparison, Barack Obama’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 amounted to more than 800 US$ billions. The US mobilized more than twice as much as the Juncker plan, in fresh money, and right at the beginning of the crisis.

To sum up, the plan and the guidelines are welcome in that they put investment back to the centre of the stage. But, as is the norm with Europe, they are too little, far too little, to put the continent back on track, and to reverse the investment trend of the last three decades.

In an ideal world, the crisis and deflation would be dealt with by means of a vast European investment program, financed by the European budget and through Eurobonds. Infrastructures, green growth, the digital economy, are just some of the areas for which the optimal scale of investment is European, and for which a long-term coordinated plan is necessary. That will not happen, however, for the fierce opposition of Germany and other northern countries to any hypothesis of debt mutualisation.

The solution must therefore be found at national level, without losing the need for European-wide coordination, that would guarantee effective and fiscally sustainable investment programs. With Kemal Dervis I recently proposed that the EU adopt a golden rule, similar in spirit to the one implemented in the United Kingdom between 1998 and 2009. The rule requires government current expenditure to be financed from current revenues, while public debt may be used to finance capital accumulation. Investment expenditure, in other words, could be excluded from deficit calculation, without any limit. Such a rule would stabilize the ratio of debt to GDP, and would ensure intergenerational equity (future generations would be called to partially finance the stock of public capital bequeathed to them). Last, but especially in the current situation not least, putting in place such a rule would not require treaty changes, but just an unanimous Council deliberation.

But there’s more in our proposal. The golden rule is not a new idea, and in the past it has been criticized on the ground that it introduces a bias in favor of physical capital; expenditure that – while classified as current – is crucial for future growth (in many countries spending for education would be more growth enhancing than building new highways) would be penalized by the golden rule. This criticism, however, can be turned around and transformed into a strength. At regular intervals, for example every seven years, in connection with the European budget negotiation, the Commission, the Council and the Parliament could find an agreement on the future priorities of the Union, and make a list of areas or expenditure items exempted from deficit calculation for the subsequent years. Joint programs between neighboring countries could be encouraged by providing European Investment Bank co-financing. What Dervis and I propose is in fact returning to industrial policy, through a political and democratic determination of the EU long-term objectives. The entrepreneurial State, through public investment, would once again become the centerpiece of a large-scale European industrial policy, capable of implementing physical as well as intangible investment in selected strategic areas. Waiting for a real federal budget, the bulk of investment would remain responsibility of national governments, in deference to the principle of subsidiarity. But the modified golden rule would coordinate and guide it towards the development and the well-being of the Union as a whole.

Ps an earlier and shorter version of this piece was published in Italian on December 31st in the daily Il Sole 24 Ore.

1. Specifically, the provisions are the following:

Member States in the preventive arm of the Pact can deviate temporarily from their medium-term budget objective or from the agreed fiscal adjustment path towards it, in order to accommodate investment, under the following conditions:

- Their GDP growth is negative or GDP remains well below its potential (resulting in an output gap greater than minus 1.5% of GDP);

- The deviation does not lead to non-respect of the 3% deficit reference value and an appropriate safety margin is preserved;

- Investment levels are effectively increased as a result;

- Eligible investments are national expenditures on projects co-funded by the EU under the Structural and Cohesion policy (including projects co-funded under the Youth Employment Initiative), Trans-European Networks and the Connecting Europe Facility, as well as co-financing of projects also co-financed by the EFSI.

- The deviation is compensated within the timeframe of the Member State’s Stability or Convergence Programme (Member States’ medium-term fiscal plans).

ECB: Great Expectations

After the latest disappointing data on growth and indeflation in the Eurozone, all eyes are on today’s ECB meeting. Politicians and commentators speculate about the shape that QE, Eurozone edition, will take. A bold move to contrast lowflation would be welcome news, but a close look at the data suggests that the messianic expectation of the next “whatever it takes” may be misplaced.

Faced with mounting deflationary pressures, policy makers rely on the probable loosening of the monetary stance. While necessary and welcome, such loosening may not allow embarking the Eurozone on a robust growth path. The April 2014 ECB survey on bank lending confirms that, since 2011, demand for credit has been stagnant at least as much as credit conditions have been tight. Easing monetary policy may increase the supply for credit, but as long as demand remains anemic, the transmission of monetary policy to the real economy will remain limited. Since the beginning of the crisis, central banks (including the ECB) have been very effective in preventing the meltdown of the financial sector. The ECB was also pivotal, with the OMT, in providing an insurance mechanism for troubled sovereigns in 2012. But the impact of monetary policy on growth, on both sides of the Atlantic, is more controversial. This should not be a surprise, as balance sheet recessions increase the propensity to hoard of households, firms and financial institutions. We know since Keynes that in a liquidity trap monetary policy loses traction. Today, a depressed economy, stagnant income, high unemployment, uncertainty about the future, all contribute to compress private spending and demand for credit across the Eurozone, while they increase the appetite for liquidity. At the end of 2013, private spending in consumption and investment was 7% lower than in 2008 (a figure that reaches a staggering 18% for peripheral countries). Granted, radical ECB moves, like announcing a higher inflation target, could have an impact on expectations, and trigger increased spending; but these are politically unfeasible. It is not improbable, therefore, that a “simple” quantitative easing program may amount to pushing on a string. The ECB had already accomplished half a miracle, stretching its mandate to become de facto a Lender of Last Resort, and defusing speculation. It can’t be asked to do much more than this.

While monetary policy is given almost obsessive attention, there is virtually no discussion about the instrument that in a liquidity trap should be given priority: fiscal policy. The main task of countercyclical fiscal policy should be to step in to sustain economic activity when, for whatever reason, private spending falters. This is what happened in 2009, before the hasty and disastrous fiscal stance reversal that followed the Greek crisis. The result of austerity is that while in every single year since 2009 the output gap was negative, discretionary policy (defined as change in government deficit net of cyclical factors and interest payment) was restrictive. In truth, a similar pattern can be observed in the US, where nevertheless private spending recovered and hence sustained fiscal expansion was less needed. Only in Japan, fiscal policy was frankly countercyclical in the past five years.

As Larry Summers recently argued, with interest rates at all times low, the expected return of investment in infrastructures for the United States is particularly high. This is even truer for the Eurozone where, with debt at 92%, sustainability is a non-issue. Ideally the EMU should launch a vast public investment plan, for example in energetic transition projects, jointly financed by some sort of Eurobond. This is not going to happen for the opposition of Germany and a handful of other countries. A second best solution would then be for a group of countries to jointly announce that the next national budget laws will contain important (and coordinated) investment provisions , and therefore temporarily break the 3% deficit limit. France and Italy, which lately have been vocal in asking for a change in European policies, should open the way and federate as many other governments as possible. Public investment seems the only way to reverse the fiscal stance and move the Eurozone economy away from the lowflation trap. It is safe to bet that even financial markets, faced with bold action by a large number of countries, would be ready to accept a temporary deterioration of public finances in exchange for the prospects of that robust recovery that eluded the Eurozone economy since 2008. A change in fiscal policy, more than further action by the ECB, would be the real game changer for the EMU. But unfortunately, fiscal policy has become a ghost. A ghost that is haunting Europe…

The Italian Job

A follow-up of the post on public investment. I had said that the resources available based on my calculation were to be seen as an upper bound, being among other things based on the Spring forecasts of the Commission (most likely too optimistic).

And here we are. On Friday the IMF published the result of its Article IV consultation with Italy, where growth for 2013 is revised downwards from -1.3% to -1.8%.

In terms of public finances, a crude back-of-the-envelop estimation yields a worsening of deficit of 0.25% (the elasticity is roughly 0.5). This means that in the calculation I made based on the Commission’s numbers, the 4.8 billions available for 2013 shrink to 1.5 once we take in the IMF numbers. It is worth reminding that besides Germany, Italy is the only large country who can could benefit of the Commission’s new stance.

And while we are at Italy, the table at page 63 of the EC Spring Forecasts (pdf) is striking. The comparison of 2012 with the annus horribilis 2009 shows that private demand is the real Italian problem. The contribution to growth of domestic demand was of -3.2% in 2009, and -4.7% in 2012! In part this is because of the reversed fiscal stimulus; but mostly because of the collapse of consumption (-4.2% in 2012, against -1.6% in 2009). Luckily, the rest of the world is recovering, and the contribution of net exports, went from -1.1% in 2009 to 3.0% in 2012. This explains the difference in GDP growth between the -5.5% of 2009 and the -2.4% of 2012.

Italian households feel crisis fatigue, and having depleted their buffers, they are today reducing consumption. I remain convinced that strong income redistribution is the only quick way to restart consumption. Looking at the issues currently debated in Italy, this could be attempted reshaping both VAT and property taxes so as to impact the rich and the very rich significantly more than the middle classes. The property tax base should be widened to include much more than just real estate, and an exemption should be introduced (currently in France it is 1.2 millions euro per household). Concerning VAT, a reduction of basic rates should be compensated by a significant increase in rates on luxury goods.

Chances that this will happen?