Archive

Labour Costs: Who is the Outlier?

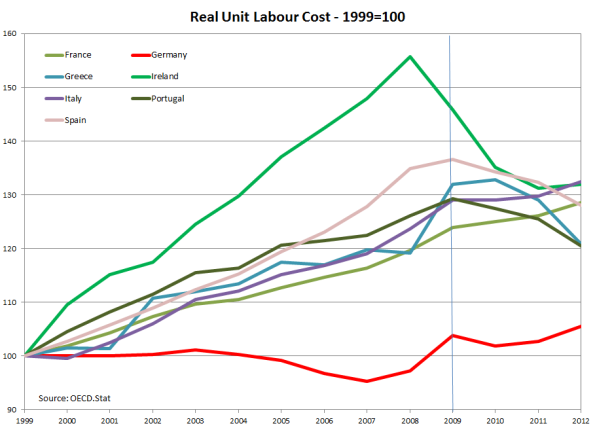

Spain is today the new model, together with Germany of course, for policy makers in Italy and France. A strange model indeed, but this is not my point here. The conventional wisdom, as usual, almost impossible to eradicate, states that Spain is growing because it implemented serious structural reforms that reduced labour costs and increased competitiveness. A few laggards (in particular Italy and France) stubbornly refuse to do the same, thus hampering recovery across the eurozone. The argument is usually supported by a figure like this

And in fact, it is evident from the figure that all peripheral countries diverged from the benchmark, Germany, and that since 2008-09 all of them but France and Italy have cut their labour costs significantly. Was it costly? Yes. Could convergence have made easier by higher inflation and wage growth in Germany, avoiding deflationary policies in the periphery? Once again, yes. It remains true, claims the conventional wisdom, that all countries in crisis have undergone a painful and necessary adjustment. Italy and France should therefore also be brave and join the herd.

Think again. What if we zoom out, and we add a few lines to the figure? From the same dataset (OECD. Productivity and ULC By Main Economic Activity) we obtain this:

It is unreadable, I know. And I did it on purpose. The PIIGS lines (and France) are now indistinguishable from other OECD countries, including the US. In fact the only line that is clearly visible is the dotted one, Germany, that stands as the exception. Actually no, it was beaten by deflation-struck Japan. As I am a nice guy, here is a more readable figure:

The figure shows the difference between change in labour costs in a given country, and the change in Germany (from 1999 to 2007). labour costs in OECD economies increased 14% more than in Germany. In the US, they increased 19% more, like in France, and slightly better than in virtuous Netherlands or Finland. Not only Japan (hardly a model) is the only country doing “better” than Germany. But second best performers (Israel, Austria and Estonia) had labour costs increase 7-8% more than in Germany.

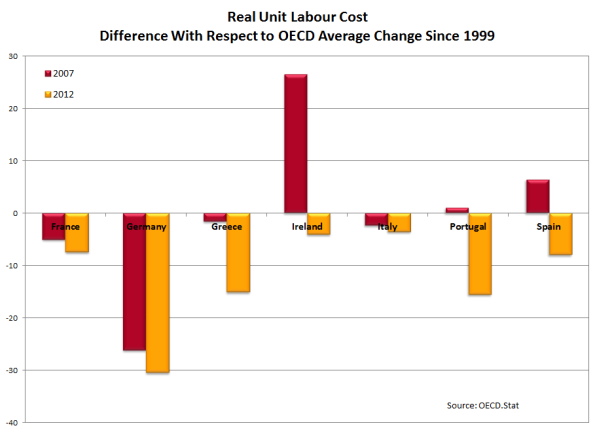

Thus, the comparison with Germany is misleading. You should never compare yourself with an outlier! If we compare European peripheral countries with the OECD average, we obtain the following (for 2007 and 2012, the latest available year in OECD.Stat)

If we take the OECD average as a benchmark, Ireland and Spain were outliers in 2007, as much as Germany; And while since then they reverted to the mean, Germany walked even farther away. It is interesting to notice that unreformable France, the sick man of Europe, had its labour costs increase slightly less than OECD average.

Of course, most of the countries I considered when zooming out have floating exchange rates, so that they can compensate the change in relative labour costs through exchange rate variation. This is not an option for EMU countries. But this means that it is even more important that the one country creating the imbalances, the outlier, puts its house in order. If only Germany had followed the European average, it would have labour costs 20% higher than their current level. There is no need to say how much easier would adjustment have been, for crisis countries. Instead, Germany managed to impose its model to the rest of the continent, dragging the eurozone on the brink of deflation.

What is enraging is that it needed not be that way.

Blame the World?

Yesterday’s headlines were all for Germany’s poor performance in the second quarter of 2014 (GDP shrank of 0.2%, worse than expected). That was certainly bad news, even if in my opinion the real bad news are hidden in the latest ECB bulletin, also released yesterday (but this will be the subject of another post).

Not surprisingly, the German slowdown stirred heated discussion. In particular Sigmar Gabriel, Germany’s vice-chancellor, blamed the slowdown on geopolitical risks in eastern Europe and the Near East. Maybe he meant to be reassuring, but in fact his statement should make us all worry even more. Let me quote myself (ach!), from last November:

Even abstracting from the harmful effects of austerity (more here), the German model cannot work for two reasons: The first is the many times recalled fallacy of composition): Not everybody can export at the same time. The second, more political, is that by betting on an export-led growth model Germany and Europe will be forced to rely on somebody else’s growth to ensure their prosperity. It is now U.S. imports; it may be China’s tomorrow, and who know who the day after tomorrow. This is of course a source of economic fragility, but also of irrelevance on the political arena, where influence goes hand in hand with economic power. Choosing the German economic model Europe would condemn itself to a secondary role.

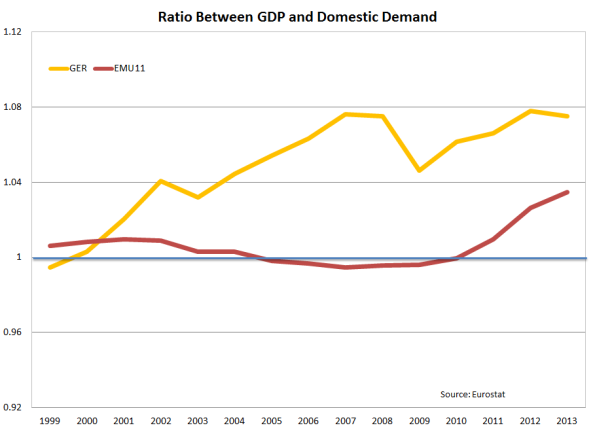

I have emphasized the point I want to stress, once again, here: adopting an export-led model structurally weakens a country, that becomes unable to find, domestically, the resources for sustainable and robust growth. And here we are, the rest of the world sneezes, and Germany catches a cold. The problem is that we are catching it together with Germany:

The ratio of German GDP over domestic demand has been growing steadily since 1999 (only in 19 quarters out of 72, barely a third, domestic demand grew faster than GDP). And what is more bothersome is that since 2010 the same model has been adopted by imposed to the rest of the eurozone. The red line shows the same ratio for the remaining 11 original members of the EMU, that was at around one for most of the period, and turned frankly positive with the crisis and implementation of austerity.It is the Berlin View at work, brilliantly and scaringly exposed by Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann just a couple of days ago. We are therefore increasingly dependent on the rest of the world for our (scarce) growth (the difference between the ratio and 1 is the current account balance).

It is easy today to blame Putin, or China, or tapering, or alien invasions, for our woes. Easy but wrong. Our pain is self-inflicted. Time to change.

Fiscal Expansion or What?

The newly born Italian magazine Pagina99 published a piece I wrote on rebalancing in Europe after the German elections. Here is an English version.

The preliminary estimates for 2013 released by the German Federal Statistical Office, depict a mixed picture. Timid signs of revival in domestic demand do not seem able to compensate for the slowdown in exports to other countries in the euro zone, still mired in weak or negative growth rates. The German economy does not seem able to ignore the economic health of its European partners. In spite of fierce resistance of Germany policymakers, there is increasing consensus that the key to a durable exit from the Eurozone crisis can only be found in restoring symmetry in the adjustment following the crisis. The reduction of expenditure and deficits in the Eurozone periphery, that is currently happening, needs to be matched by an increase of expenditure and imports by the core, in particular by the Netherlands and Germany (Finland and Austria have actually drastically reduced their trade surpluses). In light of the coalition agreement signed by the CDU and the SPD, it seems unlikely that major institutional innovation will happen in the Eurozone, or that private demand in Germany will increase sufficiently fast to have an impact on imbalances at the aggregate level. This leaves little alternative to an old-fashioned fiscal expansion in Germany.

The Eurozone reaction to the sovereign debt crisis, so far, has focused on enhancing discipline and fiscal restraint. Germany, the largest economy of the zone, and its largest creditor, was pivotal in shaping this approach to the crisis. The SPD, substantially shared the CDU-Liberal coalition view that the crisis was caused by fiscal profligacy of peripheral member countries, and that little if any risk sharing should be put in place (be it a properly functioning banking union, or some form of debt mutualisation). The SPD also seems to support Mrs Merkel’s strategy of discretely looking elsewhere when the ECB is forced to stretch its mandate to respond to exceptional challenges, while refusing all discussion on introducing the reform of the bank statute in a wider debate on Eurozone governance. This consensus explains why European matters take relatively little space in the 185 pages coalition agreement.

This does not mean that the CDU-SPD government will have no impact on Eurozone rebalancing. The most notable element of the coalition agreement is the introduction of a minimum wage that should at least partially attenuate the increasing dualism of the German labour market. This should in turn lead, together with the reduction of retirement age to 63 years, to an increase of consumption. The problem is that these measures will be phased-in slowly enough for their macroeconomic impact to be diluted and delayed.

Together with European governance, the other missing character in the coalition agreement is investment; this is surprising because the negative impact of the currently sluggish investment rates on the future growth potential of the German economy is acknowledged by both parties; yet, the negotiations did not include direct incentives to investment spending. The introduction of the minimum wage, on the other hand, is likely to have conflicting effects. On the one hand, by reducing margins, it will have a negative impact on investment spending. But on the other, making labour more expensive, it could induce a substitution of capital for labour, thus boosting investment. Which of these two effects will prevail is today hard to predict. But it is safe to say that changes in investment are not likely to be massive.

To summarize, the coalition agreement will have a small and delayed impact on private expenditure in Germany. Similarly, the substantial consensus on current European policies, leaves virtually no margin for the implementation of rebalancing mechanisms within the Eurozone governance structure.

Thus, there seems to be little hope that symmetry in Eurozone rebalancing is restored, unless the only remaining tool available for domestic demand expansion, fiscal policy, is used. The German government should embark on a vast fiscal expansion program, focusing on investment in physical and intangible capital alike. There is room for action. Public investment has been the prime victim of the recent fiscal restraint, and Germany has embarked in a huge energetic transition program that could be accelerated with beneficial effects on aggregate demand in the short run, and on potential GDP in the long run. Finally, Germany’s public finances are in excellent health, and yields are at an all-times low, making any public investment program short of pure waste profitable. Besides stubbornness and ideology, what retains Mrs Merkel?

Small Germany?

Today we learn from Daniel Gros, on Project Syndicate that the emphasis on German surplus is misplaced:

The discussion of the German surplus thus confuses the issues in two ways. First, though the German economy and its surplus loom large in the context of Europe, an adjustment by Germany alone would benefit the eurozone periphery rather little. Second, in the global context, adjustment by Germany alone would benefit many countries only a little, while other surplus countries would benefit disproportionally. Adjustment by all northern European countries would have double the impact of any expansion of demand by Germany alone, owing to the high degree of integration among the “Teutonic” countries.

Fascinating. The bulk of the argument is that Germany is a small player in the global economy, and therefore that its actions have no impact. I have two objections to Gros’ argument. Read More

Surprise! I (sort of) Agree with Olli Rehn!

Olli Rehn wrote a balanced piece on Germany’s current account surplus. To sum it up:

- He acknowledges that Germany’s surplus is a problem.

- He acknowledges (albeit indirectly) that the initial source of the problem were capital flows from Germany and the core to the periphery; flows that did not go into productive investment but fueled bubbles.

- He (correctly) argues that over the long run some excess savings from Germany is justified by the need to provide for an ageing population.

- He points out that investment has been too low and needs to increase (possible within the framework of an energy transition).

- He also mentions, without mentioning it, the problem of excessively low wages and pauperisation of the labour force, calling for increases in wages and reduction in taxes to boost domestic demand.

This seems to me a reasonable analysis, and I would welcome an official position of the Commission along these lines. Yet, I think that what is missing in Rehn’s piece, and in most of the current debate, is a clear articulation of between the long and the short run.

I would not object on the need for Germany to run modes surpluses on average over the next years, to pay for future pensions and welfare. It is after all a mature and ageing country. Even more, I would agree with the argument that low wages need to increase, and that bottlenecks that prevent domestic demand expansion should be removed. In other words, I would most likely agree on the Commission’s prescriptions for the medium-to-long run.

Nevertheless, there is a huge hole in Olli Rehn’s analysis, that worries me a bit. Rehn seems to overlook the need to do something here and now. Today, with the periphery of the eurozone stuck in recession, emerging economies sputtering, and continuing jobless growth in the US, the world desperately needs a boost from countries that can afford it. And unfortunately there are not many of these.

Germany is instead siphoning off global demand, making the rest of the world carry its economy when it should do the opposite. As a quick reversal of private demand is unlikely, (this, I repeat should be a medium run target), I see no other option in hte very short run than a substantial fiscal expansion.

A cooperative Germany should implement short run expansionary policies (the need for public investment is undeniable), while working to rebalance consumption, investment and savings in the medium run, with the objective of a small current account surplus in the medium run.

That, incidentally, would not make them Good Samaritans. Ending this endless recession in the eurozone (yes I know, it is technically over; but how happy can we be with growth rates in the zero-point range?) is in the best interest of Germany as much as of the rest of the eurozone (and of the world).

A clear articulation between the different priorities in the short and in the medium-long run would benefit the debate. The problem is that then Olli Rehn should acknowledge that in the short run there is no alternative to expansionary fiscal policies in the eurozone core. That would be asking too much…

Incomprehensible? Really?

Germany rejected the US Treasury’s criticism of the country’s export-focused economic policies as “incomprehensible”. Much has been said about that. Let me just add some pieces of evidence, just to gather them all in the same place.

Exhibit #1: Net Lending Evolution

Note#1 : I took net lending because because net income flows from residents to non residents (not captured by the current account) may be an important part of a country’s net position (most notably in Ireland). Note #2: I took away France and Italy from the two groups called “Core” and “Periphery”, because their net position was relatively small as percentage of GDP in 2008, and changed relatively little.

Read More

Lilliput in Deutschland

Following the widely discussed U.S. Treasury report on foreign economic and currency policies, that for the first time blames Germany explicitly for its record trade surpluses, I published an op-ed on the Italian daily Il Sole 24 Ore (in Italian), comparing Germany with China. My argument there is the following:

- Before the crisis the excess savings of China and Germany, the two largest world exporters, contributed to the growing global imbalances by absorbing the excess demand of the U.S. and of other economies (e.g., the Eurozone periphery) that made the world economy fragile. (more here)

- In the past decade, China seems to have grasped the problems yielded by an export-led growth model, and tried to rebalance away from exports (and lately investment) towards consumption (more here). The adjustment is slow, sometimes incoherent, but it is happening.

- Germany walked a different path, proudly claiming that the compression of domestic demand and increased exports were the correct way out of the crisis (as well as the correct model for long-term growth)

- Germany’s economic size, its position of creditor, and its relatively better performance following the sovereign debt crisis, (together with a certain ideological complicity from EC institutions) allowed Germany to impose the model based on austerity and deflation to peripheral eurozone countries in crisis.

- Even abstracting from the harmful effects of austerity (more here), I then pointed out that the German model cannot work for two reasons: The first is the many times recalled fallacy of composition): Not everybody can export at the same time. The second, more political, is that by betting on an export-led growth model Germany and Europe will be forced to rely on somebody else’s growth to ensure their prosperity. It is now U.S. imports; it may be China’s tomorrow, and who know who the day after tomorrow. This is of course a source of economic fragility, but also of irrelevance on the political arena, where influence goes hand in hand with economic power. Choosing the German economic model Europe would condemn itself to a secondary role.

I would add that the generalization of the German model to the whole eurozone is leading to increasing current account surpluses. Therefore, this is not simply a European problem anymore. By running excess savings as a whole, we are collectively refusing to chip in the ongoing fragile recovery. The rest of the world is right to be annoyed at Germany’s surpluses. We continue to behave like Lilliput, refusing to play our role of large economy.

Let me conclude by noticing that today in his blog Krugman shows that sometimes a chart is worth a thousand (actually 748) words:

Parallel Universes

So, on today’s FT the German finance minister Wolfgang Schauble forcefully argued that Europe is on the right track, that austerity is paying off, and that “Despite what the critics of the European crisis management would have us believe, we live in the real world, not in a parallel universe where well-established economic principles no longer apply.”

He then proceeds listing all the benefits that austerity and “well-established economic principles” brought to Germany, and to other countries that followed them. Today, he claims, Germany has strong growth, fueled by domestic demand, and grounded on robust investment and innovation.

Ok, let’s see who lives in a parallel world. Read More

Wait Before Toasting

Just a quick note on yesterday’s announcement by the Commission that virtuous countries will be able, in 2013 and 2014, to run deficits and to implement public investment projects.

Faced with an excessive enthusiasm, Commissioner Rehn quickly framed this new approach within very precise limits, that are worth transcribing:

The Commission will consider allowing temporary deviations from the structural deficit path towards the Medium-Term Objective (MTO) set in the country specific recommendations, or the MTO for Member States that have reached it, provided that:

(1) the economic growth of the Member State remains negative or well below its potential

(2) the deviation does not lead to a breach of the 3% of GDP deficit ceiling, and the public debt rule is respected; and

(3) the deviation is linked to the national expenditure on projects co-funded by the EU under the Structural and Cohesion policy, Trans-European Networks (TEN) and Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) with positive, direct and verifiable long-term budgetary effect.

This application of the provisions of the SGP concerning temporary deviations from the MTO or the adjustment path towards it is related to the current economic conditions of large negative output gap. Once these temporary conditions are no longer in place and the Member State is forecast to return to positive growth, thus approaching its potential, any deviation as the above must be compensated so that the time path towards the MTO is not affected.

For once, the Commission is not vague about what is allowed and what is not, and the result is that this announcement will turn out to be nothing more than a well conceived Public Relations operation. Allow me to attach some numbers to the Commission proposal.

Read more

Wrong Models

Sebastian Dullien has a very interesting Policy Brief on the “German Model”, that is worth reading. Analyzing the Schroeder reforms of 2003-2005, it shows that it fundamentally boiled down to encouraging part-time contracts, but it did not touch the core of German labour market regulation:

Note, however, what the Schröder reforms did not do. They did not touch the German system of collective wage bargaining. They did not change the rules on working time. They did not make hiring and firing fundamentally easier. They also did not introduce the famous working-time accounts and the compensation for short working hours, which helped Germany through the crisis of 2008–9.

Thus, Dullien concludes, the standard Berlin View narrative, i.e. the success of the German Economy is due to fiscal consolidation and structural reforms in particular in labour markets, needs to be reassessed to say the very least. But there is more than this.